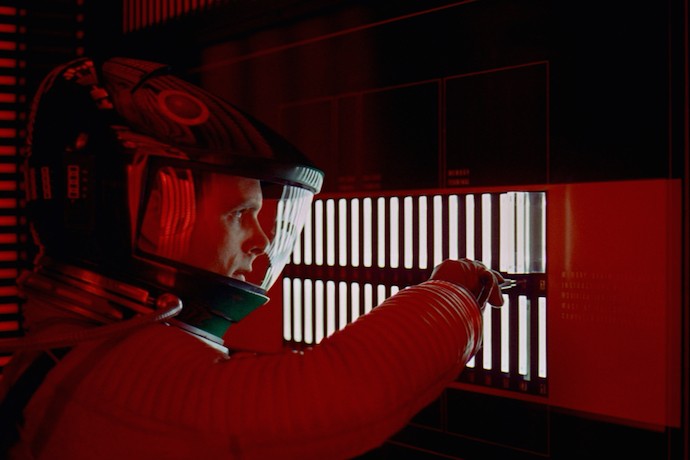

Since the onset of the Industrial Revolution, Western nations have harbored a collective anxiety about the replacement of human jobs by mechanized labor. Economists have long tried to predict which jobs will be lost to machines, but they offer no guarantees. People fear being replaced.

But robots aren’t just taking jobs. Last Monday, at a Volkwagen plant in Germany, one robot killed an employee.

The machine in question—a sophisticated automotive assembly line robot—normally operates within a circumscribed area, grabbing parts and manipulating them according to a predetermined process. As a team of workers was setting it up, however, the robot grabbed one of them—a 22-year-old man—and crushed him against a metal plate.

Volkswagen spokesman Heiko Hillwig has indicated that human error was likely to blame, not the bot. Critics are not so sure. Speculation that the robot is, or should be, to blame has already run rampant online. This isn’t just idle speculation on Twitter. It’s a reflection of much deeper fears about the world to come.

It was the cyborg!

If you’ve ever kicked a TV or mumbled threats at your computer, you’re familiar with how easy it is to assign human agency to unconscious machines. We seem especially prone to anthropomorphizing them when they frustrate us. My toaster is invisible to me when it’s working, but if it misbehaves I find myself angrily unplugging it, chastising it, and otherwise making my will known.

Today, our tendency to blame inanimate objects has begun to merge with that long-standing human fear about the rise of robotics. Even during the Great Depression workers were fretting about robots taking jobs. Newspapers ran sensational stories about bots and other machines “turning” on their masters and killing humans.

According to one 1932 story that ran in Louisiana, an inventor was demonstrating his cyborg’s precision with a firearm when the cyborg grabbed the gun, turned on the master, and critically wounded him. Of course, this never happened. As nearly as historians can tell, the inventor accidentally discharged the firearm while nestling it in his invention’s “hand.” Still, the market for such stories speaks to our simultaneous feelings of fascination and fear about robots.

However we might feel about the Volkswagen robot, German prosecutors will make the ultimate determination of who bears legal blame for the death of the young worker. German news agencies report that prosecutors are currently considering charges, and debating about whom to blame. As factories become further roboticized, more of these accidents will surely occur. We are in uncharted waters. The way we assign blame in these early cases will set a course, influencing how we define the agency and blameworthiness of machines.

The case for suing robots

There are many parties against whom German prosecutors could press charges, and their decision will have significant moral and economic consequences. Prosecutors could sue the business owner, the robot’s hardware designer, the robot’s software designer, or—most interestingly—the robot itself. Each option would have major consequences for future incentives and innovations in robotic labor.

Suing a robot might sound crazy, but the other options aren’t very good, either. It would be unreasonable to hold a factory owner accountable for every machine that she owns; as long as owners have taken certain precautions, we usually absolve them of blame for what happens in the course of work. It’s even less intuitive to consider designers responsible. Few people blame Toyota when they crash their cars. But, while in car crashes our moral sensibility and intuition causes us to blame users (that is, drivers), that seems less likely in the robotics context.

Surely no one would want to blame the workers using the robot for the incident in the VW factory, so we aren’t left with many appealing options. Our intuition to blame the bot may not be so crazy after all. We blame drivers who crash their cars because we tend to view drivers as the agent responsible for operating a machine. If we come to believe that robots themselves are agents whose behavior, like our own, is not entirely predictable, we may want to sue bots themselves, rather than user-workers. There is no guarantee that we will come to feel this way or that we must, but it is certainly one possibility.

Whether or not we are replaced by robots, chances are, in the coming decades, more and more of us will work beside them. Right now our moral intuitions about robots are not well tuned, and we’re facing new problems that stretch our judgments. All of us, not just prosecutors, will need to start coming up with answers soon.