A new statement by Orthodox Christian theologians—some of whom sign from Russia—dramatically illustrates what’s at stake in this war of (mostly) Christians against Christians, and what implications it has for the American scene.

The statement sets its organizers in opposition to “Russian World” (Russkii Mir) teaching, which is essentially a contemporary Russian version of the Nazis’ “blood and soil” ideology. As the authors explain, Russian World teaches that “there is a transnational Russian sphere or civilization, called Holy Russia or Holy Rus’, which includes Russia, Ukraine and Belarus (and sometimes Moldova and Kazakhstan).”

This Russian world, according to the ideology, has Moscow as its administrative center and Kyiv as its spiritual heart: both Ukrainian and Russian Orthodox leaders refer to the “one Kyivan font” from which the newly-baptized Christian people of both nations arose. The Russian world is further held to be unified by a common language, a common church (the Russian Orthodox Church, Moscow Patriarchate)—and a common political leader: Vladimir Putin.

In theory, all of these unifying factors work together to support “a common distinctive spirituality, morality, and culture,” which are threatened by a decadent West that has lost its way:

Against this “Russian world” (so the teaching goes) stands the corrupt West, led by the United States and Western European nations, which has capitulated to “liberalism”, “globalization”, “Christianophobia”, “homosexual rights” promoted in gay parades, and “militant secularism”.

Undergirding Russkii Mir, according to the statement’s authors, is the heresy of “ethno-phyletism,” or building the church around a particular “race or tribe.”

Before you run to the dictionary—or, let’s face it, a search engine—it helps to understand the background of this charge. In theory, the Orthodox world is organized by “autocephalous,” or self-headed, churches defined by geographical territory. This is why there’s a Greek church and a Russian church, and so on. In practice, things have been messier. The historical record has been that the churches of smaller nations have relied upon those of more dominant partners.

Again, in theory, as national churches become more independent, they separate from their mother churches and go it alone. In reality, it’s highly controversial when churches break off, and sometimes a nation will force the issue to assert political, rather than religious, independence. Indeed, one of the Russian bones of contention has been Ukrainian ecclesial independence, which they claim the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Istanbul—generally regarded as the leader of the Orthodox world—has been fostering without legitimacy.

As a matter of theology, the Orthodox churches are not supposed to be defined by ethnicity, despite their territorial definitions. In practice, once again, things are much more complicated. In fact, the question gets right to the heart of what it means to maintain Orthodox tradition in the modern world:

If we hold such false principles as valid, then the Orthodox Church ceases to be the Church of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, the Apostles, the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, the Ecumenical Councils, and the Fathers of the Church. Unity becomes intrinsically impossible.

Orthodoxy is constituted by fidelity to the person and teaching of Jesus himself, as passed down through a rich intellectual heritage. Anything other than that central organizing principle betrays Orthodox identity and morality itself.

The statement rejects in considerable detail the alternatives to the Orthodox identity that it sees coming from Russkii Mir and its ecclesial sponsor Patriarch Kirill. For example, it condemns the subordination of the Kingdom of God to a particular nation or political leader. The authors are too polite to mention it, but the obvious specter here is the coopted church of Nazi Germany.

Likewise, and forcefully, the statement speaks against “division of humanity into groups based on race, religion, language, ethnicity or any other secondary feature of human existence.” They have to walk a fine line here, because Orthodoxy as a whole does not approve of sexual diversity. But once again, the point is clear: wars cannot be justified by gay pride parades, and to do so in a worship service is “particularly wicked.” Nor is it legitimate to hold Orthodoxy as somehow superior to other Christian streams or even non-Christian or secular paths, nor is it acceptable to shirk the Christian calling to actively make peace with mealy-mouthed exhortation to prayer without meaningful action.

This is a long summary, but the statement is well worth it for the ways in which it peels back the layers of pretense, corruption, and blame-shifting that Kirill habitually indulges in, such as when he recently suggested to the leader of the World Council of Churches that Russia was simply trying to save Ukraine from Western domination and itself from NATO belligerence.

It also exposes the religious underpinnings of Putin’s nationalist project. Steven Erlanger writes in the New York Times that

Mr. Putin has repeatedly asserted that Ukraine is not a real state and that the Ukrainians are not a real people, but actually Russian, part of a Slavic heartland that also includes Belarus.

This is the Russian World ideology, rooted specifically in the “one Kyivan font” of Christian baptism, which allows both secular and sacred leaders to minimize the aggression of one nation against its peaceful neighbor.

As Erlanger observes, with Putin, abetted by Kirill, all the old things seem new again; and again, they all seem to be deeply intertwined with Russia’s Christian identity:

The idea of Russia as a separate civilization from the West with which it competes goes back centuries, to the roots of Orthodox Christianity and the notion of Moscow as a “third Rome,” following Rome itself and Constantinople. [Timothy] Snyder has examined the sources of what he has called a form of Russian Christian fascism, including Ivan Ilyin, a writer born in 1883, who saw salvation in a totalitarian state led by a righteous individual.

Ilyin’s ideas have been revived and celebrated by Mr. Putin and his close circle of security men and allies like Yuri Kovalchuk, who was described recently by Mikhail Zygar, the former editor of the independent news channel TV Rain, as “an ideologue, subscribing to a worldview that combines Orthodox Christian mysticism, anti-American conspiracy theories and hedonism.”

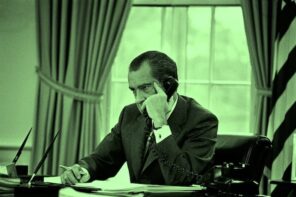

It should not go without notice that Russians are hardly the only ones to indulge in “mysticism, anti-American conspiracy theories and hedonism.” Religion Dispatches, among other outlets, is chock-full of the weird, apocalyptic visions of prosperity gospel preachers, the dispiriting conspiracy theories used by the far right to undermine the American project of liberal, multicultural democracy, and the many indulgences of the former president and his clan.

There are many conservative American thinkers who endorse some form of integralism, the belief that the state ought to promote religious morality. Some of those go further to embrace more or less openly Eastern European ethno-religious nationalism. The Orthodox statement against Russkii Mir exposes the intellectual shabbiness of the last set in particular with the simplest of reminders: the state is the state, the people of God are something different, and though the two must co-exist, one should not dominate the other.

For all his pretensions to erudition, Rod Dreher’s orthodoxy has never been anything other than Putin’s: “traditional morality, a rigorist and inflexible understanding of tradition, and veneration of Holy Russia.” Intentionally or not, the theologians have the receipts to prove it.

A broader application might be to America’s own ethno-phyletism, the increasing embrace of white nationalism by white Christians. Our denominations are no longer bounded by ethnic identity: few people these days care much about finding a German church or an Italian parish. But churches can and do sort themselves into supporters of the former president and not, or by believers who find their identity less in baptism than in white grievance and a yearning for the return of social hegemony.

Steven Erlanger ends his column with a quote from a scholar to the effect that “Putin wanted to be the father of a new Russian nation, but he is the father of a new Ukrainian nation instead.” The same might be said for his hopes to sponsor a revived Russian church, and just possibly for his dreams to use American social divisions against themselves. Any religious body wanting to counteract “division, mistrust, hatred, and violence” just got handed the tools to do so, courtesy of Orthodox thinkers and religious leaders appalled by the aggression of one of their own.