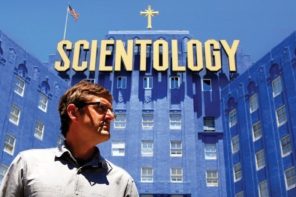

- The Church of Scientology

- Hugh Urban

- Princeton U. Press (2011)

In Los Angeles, I’ve heard a lot of stories about Scientologists. There was the jaw-dropping (and unfortunately off-the-record) one about the flagrantly unethical executive. Or the one about the articulate grip who calmly explained the religion’s tenets at the craft services table. And then there’s the stylist who has so many run-ins with proselytizing Scientologists that she calls it “getting Sci-Tied.”

What’s interesting is that all these experiences were related as momentarily discomfiting but ultimately harmless. Of course, the perception of Scientology is something else entirely. The church is seen as a scam, as a fake religion, as a refuge for credulous actors, as the domain of paranoid, exploitative leaders. It is also seen as rich, powerful, and vindictive. I’ve often heard people mock the Church of Scientology—but always in private.

This discretion is likely due to Scientology’s history of remarkable hostility toward critics. When it sees a threat, the church goes nuclear. Consider Paulette Cooper, author of The Scandal of Scientology. After her book was published in 1971, Cooper was subjected to years of harassment, including frequent lawsuits (a classic Scientology tactic), a smear campaign, and an outrageous attempt to frame her for bomb threats.

More recently, according to The Village Voice, Scientology has been digging for dirt on Trey Parker and Matt Stone, the creators of South Park, for satirizing the church in the 2005 episode “Trapped in the Closet.” The church allegedly hired investigators to go through their trash and to collect information about their staff. (Meanwhile, the most offensive thing about the episode was that it wasn’t all that funny.)

While there is something undeniably disturbing about The Church of Scientology, there’s also something fascinating about it. And maybe, if we can see past the trash-digging and the crazed celebrities, Scientology has something to teach us—if not with its doctrine, then with its particularly American nexus of religion, culture, and business.

These themes are explored in a pair of new books, both of which examine the history of the church without sensationalism or facile mockery: Janet Reitman’s Inside Scientology, which grew out of her 2005 Rolling Stone article, and The Church of Scientology by Hugh Urban, a professor at Ohio State University who studies religious secrecy.

It’s not surprising that each book has a different approach, given their provenances. In a wide-ranging and detailed history of the church, Reitman relies on journalistic scrupulousness—by her account, she did close to a hundred interviews and read “thousands of pages of Scientology doctrine,” for which she deserves our admiration and our pity. Her notes also credit the best reporting on Scientology in recent years, in particular from the St. Petersburg Times.

Urban has also done his share of interviewing, reading, and traveling, though his book is less a comprehensive history than a supposition that the church is, to some extent, a reflection of American values. He also posits a number of broad questions (maybe too broad) about how we define religion in America and about “legal and theoretical issues in the study of religion.”

In the interest of objectivity, Urban employs a simultaneous “hermeneutics of respect and hermeneutics of suspicion”—meaning that he takes Scientology’s religious claims at face value while acknowledging its illegal practices.

Reitman lets us draw our own conclusions, for the most part, while Urban wrestles with the implications of Scientology. These differing approaches are evident in their portrayals of the early years of Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard, even if the basic outline is the same.

Born in 1911, Hubbard was a prolific science-fiction writer in the fertile prewar pulp scene. By most accounts he was a charismatic man who compulsively applied his inventive gifts to his own life. A mediocre student and college dropout, he later claimed to be an engineer and nuclear physicist; an undistinguished naval officer during World War II, he later described himself as a war hero. (These exaggerations, among others, would be incorporated into his “official” church biography.)

Hubbard washed up in Pasadena after the war, where he dabbled in the occult. (According to Reitman, he also gabbed about starting a religion.) By the end of the ’40s, Hubbard was busy devising his “technology,” an alternative to psychoanalysis called “Dianetics.” Hubbard believed, or claimed to believe, that painful psychological scars, or “engrams,” could be treated with “auditing,” wherein a patient was asked to re-experience traumatic incidents—all the way back to the “birth trauma”—until the scars were healed. His 1950 book about the process, Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health, was an instant hit, quickly launching a nationwide movement.

Reitman implies that the success of Dianetics was helped by a gap in the market. Mental health providers were hard to find in 1950, and psychoanalysis, the dominant form of psychotherapy, was expensive. But at $25 a session, Hubbard’s treatment, which claimed to have cured “homosexuals, asthmatics, arthritics, and nymphomaniacs,” quickly outstripped the cost of psychoanalysis.

Reitman’s chapters on this stuff are skillfully written, and it’s easy to appreciate the general absence of editorializing. Others might not have shown the same restraint, given some of Hubbard’s antics, like his blithe dismissal of his first wife and their children. In his pre-Dianetics years, Hubbard also tried to swindle a friend—after poaching his mistress. But the worst Reitman calls Hubbard is “one of the most effective hucksters of his generation.”

Urban, in contrast, interprets Hubbard—or rather the story of him. Less interested in personal failings or the gap between myth and fact, Urban instead views the church’s narrative as a “hagiographic mythology,” a kind of prophet’s creation myth in the tradition of Joseph Smith or Elijah Muhammad. In this light, the author of Dianetics is less a huckster than a bricoleur, “a creative recycler of cultural wares,” drawing upon postwar obsessions like the occult and psychoanalysis, science fiction and science, to create a new form of treatment. A treatment that became a religion.

But did Hubbard believe his own spiritual claims? Reitman strongly suggests that in changing Dianetics into the Church of Scientology, Hubbard had mercenary motivations. She places the early church in the context of the growth of the franchising model of the 1950s, noting its corporate-inspired focus on control, uniformity, and efficiency. Like a McDonald’s, individual churches, or “orgs,” bought their products—the books, tapes, and e-meters—from the corporation, in this case “Mother Church,” and the customer experience was efficient and streamlined. Unlike McDonald’s, Mother Church received more revenues from tithing—10 percent of the org’s gross income flowed upwards, and Hubbard took 10 percent of that.

By the mid-1950s, Hubbard was most likely a multi-millionaire; by the 1970s, he had Swiss bank accounts. His cash on hand was a shoebox or four, each filled with $25,000. (You have to wonder where he put his shoes.) But Hubbard seems to have enjoyed earning money more than the money itself. He lived modestly, given his fortune, and Reitman quotes a 1972 policy letter from Hubbard: “MAKE MONEY. MAKE MORE MONEY. MAKE OTHERS PRODUCE AS TO MAKE MONEY.”

Urban too seems skeptical. While his hermeneutics don’t allow him to accuse the bricoleur of greed, he does describe the shift from therapy to religion as a pragmatic or bureaucratic decision. In the 1962 policy letter that Urban quotes, Hubbard describes the religion of Scientology as “entirely a matter for accountants and solicitors,” and that religion is “where the money is.”

Religion also had the added benefit of tax exemption—until the auditors were audited, that is. In 1967, the IRS revoked the church’s tax-exempt status, ruling that Scientology—and Hubbard—were profiting. The church fought the ruling for 26 years.

The self-described “war” between the Church of Scientology and the IRS provides a fascinating case study of the institutionalization of harassment as church policy. It clogged the courts with hundreds of lawsuits and confused IRS agents by submitting millions of mixed-up documents. It created the National Coalition of IRS Whistleblowers, which helped to bring about congressional hearings on corruption in the agency. It hired private investigators to look for “vulnerabilities” of individual agents, signs of financial pressure or alcoholism. During “Operation Snow White,” a covert group of Scientologists broke into government offices looking for documents critical of Hubbard or Scientology.

In 1993, after two years of negotiations, the IRS reinstated the church’s tax-exempt status. After withholding almost $1 billion in taxes, the church would pay a $12.5 million fine.

For Reitman, the “war” sheds light on church tactics and becomes evidence of the church’s reach and power. But Urban is more concerned with the constitutional implications. The First Amendment restricts the government from deciding what is “religion” or what is a “church,” yet in order to make sure that the religious exemption is warranted, the IRS must do just that. Urban thus quite reasonably wonders why we have left the definition of religion to the IRS.

He also points out that Scientology did not arise in a vacuum. The church “emerged within and responded to a larger culture of secrecy, paranoia, and surveillance” that characterized the Cold War years and continues in post-9/11 America. Thus, despite its penchant for underhanded activities—or even because of them—Scientology has to be considered within the context of the culture that surrounds it.

Such observations make Urban’s book well worth the read, even if it might have benefited from a narrower focus. It raises questions about the ethical, cultural, constitutional, legal, political, economic, and (of course) religious implications of Scientology—a lot of questions for such a slim volume.

Reitman’s is also worth the read for its breadth and detail. It’s also very readable. The sections on the heartbreaking death of Lisa McPherson and the rise of David Miscavige, the current “pope” of Scientology, are absolutely riveting. Reitman’s top-down approach, however, leaves the reader a little baffled about the appeal of Scientology. There’s quite a bit about marketing tactics and life in the upper echelons of the church (which apparently for many is miserable), but what do the rank and file, like that articulate grip, get out of it?

Before reading these books, I occasionally wondered if our fear and discomfort with Scientology were exaggerated. Of course it’s impossible to ignore what the media tells us about it—about the excesses of its leaders or the exploitation of its followers. Still, I wondered if the bias against Scientology were similar to the bias against Mormons or Muslims or Evangelical Christians, to the knee-jerk defining of faiths by their most extreme practices or adherents.

This may not be quite as much of a stretch as it sounds. At the end of her book, Reitman reports on the “Independent Scientology” movement, a splinter group that follows Hubbard’s teachings, but outside the auspices of the church. Some years down the road, perhaps, there may be a version of Scientology more palatable to the casual observer.

One thing I do know for sure: the next time I hear that Scientology is a “fake religion,” I will come to its defense. Reading these books has convinced me that if enough people think they have a religion, then they have a religion.

If that’s too circular for you, consider this: Hubbard may have died in 1986 but Urban tells us that at their Gold Base in Gilman Hot Springs, California, Scientologists have kept a mansion ready for Him. “The mansion is reportedly still staffed and preserved—complete with full water glasses, toothbrushes, and note pads—in the expectation that Hubbard will return in another body.”