“I’m done waiting for mainstream media to cover nonreligious people and secular issues fairly and accurately,” says Sarah Levin, a woman who wears a number of hats in the institutional secular world. “I’m done waiting for them to stop reinforcing the Christian Right’s framing on issues and failing to challenge religious privilege. And I am absolutely done waiting for them to start seeing nonreligious people as their whole selves, beyond our orientation around religion,” Levin goes on, speaking with RD in her role as director of advocacy for OnlySky Media, a new outlet focused on “exploring the post-religious perspective.” In addition to publishing content aimed at secular readers broadly, OnlySky will be conducting its own research on secular Americans, so it will no longer be necessary to “rely solely on research produced by institutions that do not, either by way of their mission or their funding sources, have an explicit interest in serving the nonreligious,” Levin explains.

On the issue of media representation of secularism and secular Americans, Levin, the founder and head of Secular Strategies and co-chair of the Democratic National Committee’s Interfaith Council, has a point. Nonreligious Americans are generally a pro-social bunch, and overwhelmingly in favor of the very rights the anti-social, anti-democratic Christian Right is actively working to take away, like voting rights, reproductive rights, and LGBTQ rights. Yet, according to the legacy media’s punditocracy, America’s rapid secularization is something we should all be terrified of.

Starting from the demonstrably false assumption that religion is essentially the only source of social cohesion, philanthropy, and pro-social behavior, prominent pundits and religion journalists (who should know much better) continually insinuate that secularization is somehow destroying the fabric of American civil society, and that the nonreligious are somehow to blame for American polarization. How, exactly, is unclear, and it could hardly be otherwise, given that both of these premises are entirely without factual basis.

Think pieces—and often even supposedly “straight” reporting—tend to ignore the empirically demonstrated fact that the social and political polarization that pervades these not-so-United States is asymmetric and significantly worse on the political Right. Not coincidentally, that side of the proverbial aisle consists largely of the conservative, mostly white Christians from whom the newly nonreligious are fleeing. These same conservative Christians, directly encouraged by their defeated president and a host of powerful Republican leaders, attempted to overturn the legitimate results of the 2020 presidential election by means that included a violent Christian nationalist insurrection in which people were injured and killed, very nearly destroying what was left of American democracy, such as it is. But, you know, there are problems with liberals and progressives too, so…

If elite pundits and journalists won’t even grapple with the basic fact of asymmetric polarization, instead falling back on a lazy “bothsidesism” that must be comforting to people of immense privilege, I suppose it’s far too much to ask for most of them to pay attention to the numerous peer-reviewed studies demonstrating that it’s precisely the Christian Right’s authoritarian culture-warring—the very dynamic that led to Donald Trump’s 2016 election with enthusiastic Christian Right backing—that has driven many to empty the pews. But even when journalists acknowledge this fact, there’s often a subtext of paternalism and victim blaming, the not-so-subtle message that these whippersnappers ought to stay in their churches and work to make them better, instead of leaving the churches to become ever more radical in their absence.

Spoiler alert: exvangelicals like myself have often spent years, even decades, trying to push evangelical Protestantism in a more humane direction from the inside, only to conclude that evangelical institutions and norms are unreformable. Journalists would know this if they considered us sources worth consulting. On a related note, Levin is far from alone in her concerns about misrepresentation of secular Americans by the press, though you would hardly know this from watching cable news or reading the legacy media, because journalists and pundits have a habit of talking over and about the religiously unaffiliated, exvangelicals, atheists, and secular advocates, rather than talking to us.

If they were to start talking to us, treating us as valuable sources and stakeholders in the national discussion around religion and politics, civil society, and pluralism, they would of course have to grapple with a very different viewpoint on American secularization than the “Chicken Little” story they insist on purveying, as if they all nodded along with Dostoevsky’s understanding that if there is no God, everything is permitted when they were undergraduates and never revisited that proposition with a more mature, critical eye, and an awareness of the great Russian novelist’s reactionary politics, Russian nationalism, and antisemitism.

Levin’s frustration with the press is thus entirely valid. The legacy media’s approach to American secularization and secularism, frankly, constitutes journalistic malpractice.

To take a recent (admittedly far from the worst) example, many secular Americans were dismayed by Michelle Boorstein’s January 14 Washington Post report on secularization and the secular movement in America. The report failed to quote a single religiously unaffiliated young American or secular advocate. Instead, it gave pride of place to observers like Georgetown University sociologist Jacques Berlinerblau—who claims that American secularism is lacking in innovation, leadership, and movement coherence—and political scientist and Baptist pastor Ryan Burge, who contends that the secular movement is “out of step” with the country and the religiously-ambivalent nones.

Kevin Bolling, executive director of the Secular Student alliance, an organization with chapters on college campuses throughout the US, told RD that reading Boorstein’s report was “disheartening,” particularly given her record as “an accomplished religion reporter with a vast catalog of well-written articles.” He continued, “Boorstein has written about numerous topics of prime interest to secular people; follows multiple leaders in the secular movement on Twitter; is an alumnus of UW Madison [which has] a large and active Secular Student Alliance chapter; and could have easily directly reached any of the twenty national nonprofits in the secular movement for comment.”

Boorstein’s article is also typical in going to great lengths to distinguish the religiously unaffiliated, aka “nones,” from atheists, agnostics, humanists, and similar self-defined nonbelievers, painting the typical “none” as someone who is basically religious but alienated from “organized religion” as they’ve known it—someone with plenty of spiritual beliefs who could, it’s implied, perhaps adopt religious affiliation again under the right conditions (something that the American elite public sphere represents as a good thing, full stop). In the case of Boorstein’s article, the implication lingers, intentionally or not, in the way she ends the piece with Burge’s assessment of the nones as “ambivalent” toward religion as a result of “polarization.” Should American society return to a less polarized state, this framing implies, perhaps religious affiliation would start to recover as well. Such thinking inevitably casts the nones in an unserious light, as if our often painful and protracted decisions to disaffiliate from religion were not thoroughly thought through.

In fact, data now show that religiously unaffiliated youth are generally no longer returning to religion as adults, as was common in the past. While it would be equally unfair and inaccurate to portray the nones as mostly atheists and agnostics when they clearly are not (although the numbers of atheists and agnostics are rising as well), the subtext that the nones haven’t fully thought through their choice to disaffiliate from religion is offensive—and it’s a prime example of how journalists talk over nones instead of to us.

Bolling, by contrast, works directly with students, which gives him valuable insight into their mindset and decision making. “Some of our students have experienced significant religion-based harm, been financially cut off, rejected by family, ostracized in their communities, kicked out of fraternities, and verbally and physically harassed,” he explains. Seeing the harm many religious believers perpetrate by acting on their religious beliefs has a powerful impact on young people, according to Bolling.

While it’s true that “there are differences and distinctions in the spectrum of spiritual, but not religious to atheist that comprises the nones,” Bolling observes, “they are rejecting religion, to some degree. Politicians, community leaders, celebrities, and corporations need to understand this younger generation doesn’t want religion pushed in their faces, won’t stand for religious nationalism, and doesn’t want one person’s freedoms to diminish their own.”

Secular community leaders also take issue with Berlinerblau’s assertion that “There has been no innovation in secular thought in 50 years,” as well as his description of the current “third wave” of secularism as lacking in leadership. Bolling pointed to the “big three” advocacy organizations—the Freedom from Religion Foundation, American Atheists, and Americans United for the Separation of Church and State—and commented on the increasing diversification of the secular movement, as a result of which “the movement has seen a more intersectional approach.”

To be sure, movement atheism has long been dominated by cisgender white men, and much work remains to be done both in terms of diversifying leadership and in terms of fully rejecting the misogyny, racism, Islamophobia, and anti-LGBTQ—especially anti-transgender—animus that characterize New Atheism. But by the same token, organized movement secularism has made significant strides in addressing both lack of diversity in leadership and bigotry in the movement, and that should be acknowledged.

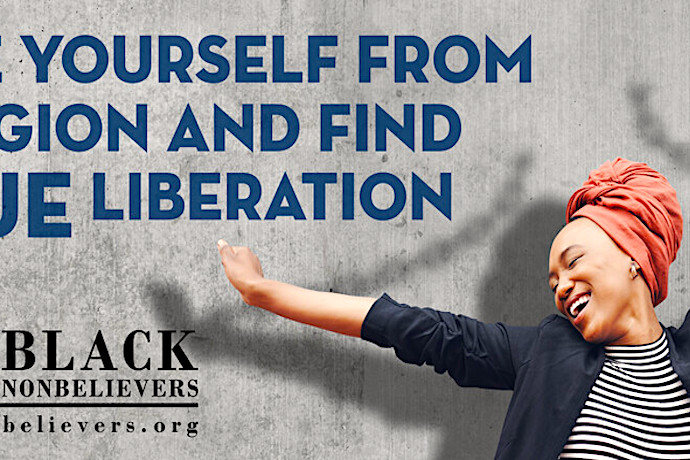

Asked what she makes of the suggestion raised in Boorstein’s article that we’re in a “third wave” of secular organizing, Mandisa Thomas, the founder and president of Black Nonbelievers, told RD, “If this is a comparison to ‘third wave feminism,’ in some ways, that could be true. There is now more of a focus on the voices of women, cis and trans alike; our concerns are being taken more seriously; and we are asserting ourselves through our content and events.”

Thomas also called Berlinerblau’s assertion of a lack of leadership in movement secularism “poorly researched,” noting that it “ignores the work of organizations like American Atheists, the American Humanist Association, and Black Nonbelievers. What does Berlinerblau, and even Boorstein, consider to be leadership, and how narrow-minded is their view?” I, too, would like to know the answer to this question.

Thomas began her organizing work in 2011 because, while data indicated that more and more young African Americans were questioning and disaffiliating from religion, there was a lack of resources available to bring them together and address their needs. Black Nonbelievers, which now has affiliates in seven cities across the United States, became a 501(c)3 nonprofit in 2014. Like the other secular leaders who spoke to RD, Thomas is frustrated with poor media representation of secular Americans and the secular movement. Her frustration extends to the paucity of coverage of BIPOC secular organizing relative to the (still sparse and often poor) coverage that majority white secular organizations and the (dead or aging and problematic) New Atheist leaders get. Despite improvement, Thomas agrees that the secular movement itself still has a diversity and inclusion problem, and maintains that the best way to address it would be for “‘allies’ to highlight the work of organizations like BN and encourage more support for us.”

Since the removal of David Silverman as its president amid allegations of financial conflicts of interest and sexual misconduct in 2018, American Atheists has also been at the forefront of diversifying the secular movement in practicing and promoting a broader, more intersectional approach to secular advocacy. The organization’s staff includes queer people, women, and African Americans in prominent roles. And, as it’s shifted away from Silverman’s “firebrand” approach to anti-religious messaging, American Atheists has begun to robustly and frequently make the case that anti-racist, feminist, and LGBTQ concerns are key church-state separation issues and should be an integral part of secular advocacy.

American Atheists’ current president, Nick Fish, told RD, “I view American Atheists’ role as providing opportunities for members of our community to more fully participate in American society, whether that be in politics, cultural institutions, or any number of other areas of life. That means doing more than simply being right about this one thing: the nonexistence of gods. It means finding partners who share our values and interests and working together to make this world a better place to live.” Clarifying that latter point, Fish noted, “Our advocacy is going to continue working to find areas of common ground with partners, regardless of their religious beliefs, while holding true to our own values around equality for all.”

Asked for his take on Berlinerblau’s comment about secularism’s lack of leadership, Fish asserted that it’s “unfair” to say “there’s no coherence or collaboration within the secular movement, which is advocating on behalf of the nonreligious.” He admitted, however, that the lack of centralization and hierarchy means that secular organizers face “challenges that simply aren’t present for religious groups.” He knowingly adds, “There are certain things that we wouldn’t want to replicate from the Religious Right even if it were structurally possible to do so because they run counter to our values as atheists and humanists.” Perhaps critics of the secular movement’s less centralized approach to leadership lack the imagination to conceive of models of leadership that differ from those employed by many religious institutions.

Regarding media representation, Fish lamented the tendency of the media to focus on New Atheist leaders and their angry, often bigoted style of atheist advocacy, when journalists should be looking to “actual policy advocates, community leaders, and grassroots activists.” Says Fish, “It’s certainly easier to always go back to the same people, but this does a tremendous disservice to promoting understanding of this community as it exists today.” As Fish sees it, journalists “don’t quite know how to talk about this elephant in the room: the fact that almost a third of Americans are no longer part of an organized religious tradition,” and no legacy media outlet does a particularly good job.

To speak of this significant percentage of the population as merely having lost something, or lacking something is at once offensive and ignorant. And so long as the legacy media continue to portray the nones in this way without actually talking to us, their reporting will inevitably imply that the nonreligious do not deserve to be taken seriously.

This brings us back to the new secular media project, OnlySky. Founded by Silicon Valley tech veteran Shawn Hardin, who now acts as its CEO, OnlySky already boasts an impressive group of contributors who are well known in secular circles. These include Pitzer College Professor Phil Zuckerman, a sociologist whose books on lived secularism are highly valued in the atheist and humanist communities.

Speaking to RD as a columnist, feature writer, and editor for OnlySky, Zuckerman explained that the outlet, which was in development from early 2020, quickly became a haven for popular atheist bloggers, including Hemant Mehta and Captain Cassidy, who were pushed out of the blogging site Patheos by onerous new guidelines requiring bloggers “to avoid politics and criticism of other worldviews, two things increasingly important to our writers since the merging of evangelicalism and conservative politics in 2016.”

But while “Patheos Nonreligious was focused tightly on the self-declared atheist and humanist demographic, OnlySky aims to serve a much broader audience—the 1 in 3 Americans who identify as having no religion,” says Zuckerman.“The hope is that OnlySky will be the main go-to media hub for secular, post-religious Americans—or for people simply interested in a secular slant on the world and on current events.”

Zuckerman and Levin, OnlySky’s director of advocacy, both share the general frustration with media misrepresentation of secularism that RD found among secular advocates. But is a secular media outlet the best way to address that issue, given that American atheist and humanist thought already exists largely in a silo, exerting little influence on anyone not already in the club?

Asked this very pointed question, Levin was ready with a powerful answer. “If we reach even a quarter of the 29% of unaffiliated [in the American population], our reach will certainly match if not exceed that of many mainstream publications.”

Marketing, too, will play an important role in getting the public to understand that the nonreligious constitute a relatively cohesive demographic worthy of attention from both advertisers and politicians. “We are often dismissed as this nebulous, loosely connected group of people that can’t possibly be reached in a targeted way that would meaningfully impact, for example, a candidate’s election prospects or a business’s bottom line,” says Levin.

OnlySky is taking on the ambitious task of changing this perception, and I can only wish them godspeed, so to speak. “The nones are not the only large and complex demographic out there,” Levin observes. “Complexity hasn’t stopped politicians or advertisers from targeting the Latino community, for example. But unlike Latinos, the nones are not generally treated as a group worth researching and targeting.” Levin’s a smart strategist, and her enthusiasm for the project is contagious. “In success,” she maintains, “OnlySky will prove that nonreligious Americans are a cultural, political and economic force to be fully reckoned with.” Given the disproportionate political power of the Christian Right and the progressive and pluralistic tendencies of the nones, let’s hope she’s right.