On August 29, 2021, in an emblematic end to America’s 20-year war in Afghanistan, the US military killed 10 innocent people, including 7 children, in an armed drone attack on a dense residential neighborhood of the capital city, Kabul. The Hellfire missile killed Zemari Ahmadi, an Afghan employee of the California-based aid organization Nutrition and Education International, and 9 of his relatives. Labeled a “righteous strike” by the US military because militant Islamists were ostensibly the target, the reality is that the attack happened, because of confirmation bias rather than evidence. This tragedy is one of many in a nation long-beleaguered by foreign invasions. Even the Taliban takeover of the Afghan national government after the catastrophic US military withdrawal from Afghanistan is indicative of Pakistan’s strategic maneuvering and strengthening of ties with China and Russia.

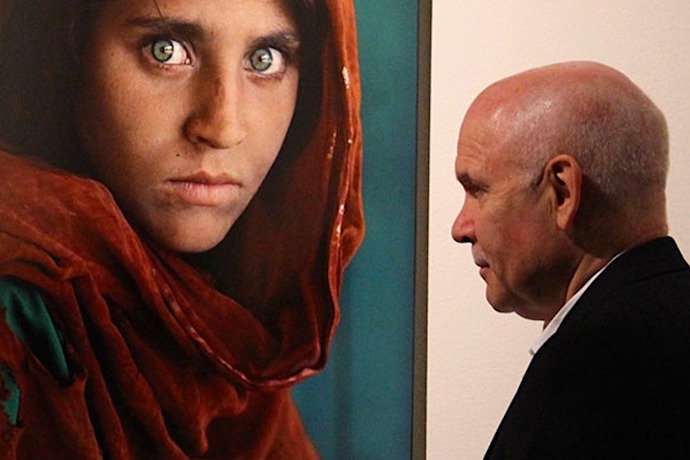

Afghans with the access to do so have fled their cherished homeland to restart their lives elsewhere. Bibi Sharbat Gula, captured on the cover of the June 1985 edition of National Geographic, is one of them. Sharbat Gula’s then-ten-year-old face is also one of the most enduring images of Afghanistan for the West. Her picture, however, isn’t merely a portrait of an Afghan girl. It’s a synecdoche for the White Savior lens through which many Americans have singularly viewed and continue to view Afghans, Afghanistan, and the US-led invasion of Sharbat’s nation of birth.

This approach to Afghans and Afghanistan diminishes the agency of Afghans themselves, reducing their rich culture to a simplistic narrative of warfare, and determining the foreign governance and institutional infrastructure of the nation for decades.

In 1984, Sharbat Gula’s photo was taken without her consent by American photographer Steve McCurry in a makeshift school at a refugee camp in Pakistan where she had fled the war in Afghanistan. She stares directly at the viewer, neither happy nor sad, but resigned. Fully present, her eyes convey intelligence, defiance, and a shyness that could also be read as wariness. The initial cover read, “Haunted eyes tell of an Afghan refugee’s fears.”

However, this was not the fear of war, but of an unknown man—and of anger at being forced to take a photograph that violated the norms of her Pashtun culture. Sharbat Gula is a Pashtun with a fierce code of respect, honor, and modesty. The notion that women and girls should not share space with a man without her or her parent’s consent is intertwined with the Pashtun code of conduct, as is the lack of direct eye contact between men and women.

In 1984, as McCurry recounted to NPR, Sharbat Gula initially covered her face when he took her photo. It was her teacher who instructed her to uncover her face. She wasn’t even asked if she wanted to participate. Arguably, the teacher’s complicity must also be called into question. However, the power dynamics at play—the White Savior bringing hope to the destitute—must be taken into consideration as must be his insistence that the photograph be taken.

As McCurry later remembered in an interview with NPR, her “incredible eyes” were the reason her photo was “the only picture” he wanted to take; yet, he didn’t, in fact, learn her name until National Geographic arranged a reunion in 2002 (which is, incidentally, the first time she ever saw the photograph herself, 17 years after it had been published). Indeed, then and now, in 2022, Sharbat Gula is referred to as “The Afghan Girl.” Not “Sharbat Gula, the Afghan Girl,” or “Bibi Sharbat Gula,” using the term of respect for women, but merely “The Afghan Girl.” Her selfhood reduced to a tagline as if she were merely the latest hashtag trending on TikTok.

Furthermore, it’s illustrative that there are many interviews of McCurry, yet hardly any that investigate and center Sharbat Gula’s own recollections and experiences of that day. This is disproportionate to the numerous reports on McCurry’s story and his book (ironically named Untold) about his encounters with Sharbat Gula and the many people who served as subjects of his photos.

In 2002, while Ms. magazine’s Spring 2002 issue focused on “freeing” Afghan women, Sharbat Gula was featured on yet another National Geographic cover. This time, her face is covered by the specific style of burqa enforced by the Taliban regime. The caption simply read, “Found: After 17 Years / An Afghan Refugee’s Story.” The article reported Sharbat Gula was an orphan when McCurry took her photo. By depicting her as an indigent waif, it played up—and into—the narrative of the Savior to the destitute Brown girl. In reality, while her mother died of appendicitis, her father was with her as they both fled to Pakistan.

Again, Sharbat Gula’s name was erased and her image subsumed into a larger narrative of the international community doing good. A charity named The Afghan Girl’s Fund was set up by National Geographic (its name was changed to The Afghan Children’s Fund in 2008). Illustrative of the misguided international aid programs that saturated Afghanistan for decades, the aid ultimately bolstered the image of the magazine instead of supporting Afghans directly themselves through access and resources.

For example, a sustainable program training Afghan photographers and supporting their careers through paid positions would have been more useful to Afghans. One more example is the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) that was established in 2002 with the “particular priority to combating violence against women and enabling their participation in the public sphere.” Yet, Afghan women themselves are not part of UNAMA’s policy-making circles, nor are they represented in UNAMA’s leadership.

In 2021, Sharbat Gula received a welcome to Rome by the Italian government. While this resettlement may seem like a positive outcome from McCurry’s photo, during the few interviews that have featured her, Sharbat Gula points out that she needed to be resettled precisely because McCurry’s photo made her a target of the Taliban regime “who don’t believe women should appear in the media.”

Speaking in her native language of Pashto to reporters with the Tolo News Agency, which is based in Afghanistan, she expressed her and her now-deceased husband’s feelings when first learning about the photo in 2002 after 17 years, “We are Pashtuns so we became nervous and very sad.” In a different interview, she stated, “The photo created more problems than benefits. It made me famous but also led to my imprisonment.” The imprisonment she’s referring to was her time served in 2016 for obtaining identity cards outside the legal realm in order to remain in Pakistan with her family, including her children, two of whom have died.

While her life and her stories of love and loss speak volumes on the multi-faceted lives of Afghans and women especially, her portrait only speaks a thousand words of media myopia, military arrogance, and cultural illiteracy.

McCurry may have taken Sharbat Gula’s photo, but he failed to portray Sharbat Gula as a human being with all the complexities that we each carry. Sharbat Gula most likely never received—nor will receive—a profit from her own photograph. And while the subject of monetizing one’s own likeness may be an issue thought to be solely for celebrities in the Instagram Age, photographers like Steve McCurry, and the media broadly, profit through money, accolades, book deals, and more jobs, while their very human subjects continue to suffer, often remaining nameless and untraceable.

Like McCurry’s exploitation of Sharbat Gula and profiting disproportionately from the rights of her image, many members of the international community—the United States’ white military industrial complex and White Feminist Majority in particular—have regarded Afghanistan merely through the point of view of war rather than as a nation of diverse peoples, a plethora of cultures, many histories, and multiple geographies—and have certainly benefited from positioning themselves as White Saviors. Afghans are portrayed and regarded as people whose way of life—including education, religions, celebrations, traditions, clothing, and food—are in need of saving by a reputedly superior White Anglo-American culture.

The US military industrial complex in Afghanistan, a term used by US President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1961, can be traced back to the 1950s during Eisenhower’s own administration. The US also played a major military role in the pivotally located nation for the duration of Sharbat Gula’s life. Most notably in the 1980s during the Reagan administration and Operation Cyclone; and most recently in every presidential administration during and since September 11, 2001.

The white (cis-hetero male) gaze is an Orientalist lens that continues to shape the understandings of the histories of Central Asian and Afghanistan, including how narratives of Afghans themselves are told. Orientalism, as defined in cultural critic Edward Said’s 1978 seminal work of the same name, is in part defined as pejorative perceptions of the Orient from a colonialist perspective, which regard people living in the Middle East as well as South, Central, and East Asia as “less than.”

Within the context of the present-day geopolitical landscape, McCurry and many media outlets, the US military industrial complex, and white feminists have reaped rich rewards by perpetuating disparaging poverty porn tropes of Afghans and Afghanistan to serve their respective culturally illiterate Savior agendas.

Specifically, the condescending and erroneous assumption that invading Afghanistan post-September 11, 2001 would “liberate” Afghan women and girls was widely held, including by the George W. Bush administration and First Lady Laura Bush. And, perhaps not surprisingly, according to Wendy S. Hesford and Wendy Kozol, such arguments in fact “renewed interest in the anonymous Afghan girl.”

McCurry’s cover photo of Sharbat Gula reified the white (woman’s) view that regards Afghan women as objects of white cis-hetero saving. Sharbat Gula in a tattered chador, and in other photos displaying her nail-bitten fingers lined with dirt, simplified the narrative of Afghanistan. Rather than instigate questions such as whether or not Afghans themselves wanted war and what the ultimate cost would be to Afghans and Americans alike, Steve McCurry’s portrayal of Sharbat Gula made the narrative of a US-led invasion into Afghanistan palatable to many Americans. McCurry’s depiction of Sharbat Gula as a helpless and hapless exotic creature was also capitalized upon by a White-led military industrial complex and the White Feminist Majority to justify their use of force and do-gooder image to an American public that viewed Afghans as The Other post-9/11.

The priorities, ideas, and aspirations of Afghans, and particularly Afghan women and girls themselves, were—and continue to be—negated. In her first radio address on November 17, 2001, then-First Lady Laura Bush seemingly spoke for Afghan women, stating, “Because of our recent military gains in much of Afghanistan, women are no longer imprisoned in their homes. They can listen to music and teach their daughters without fear of punishment. The fight against terrorism is also a fight for the rights and dignity of women.” Afghan women also became the cause célèbre for other straight white, primarily socioeconomically élite women, including actresses Susan Sarandon and Meryl Streep and former head of the National Organization for Women, Ellie Smeal.

Yet, where are these white women now to support Afghan women’s rights? How much did they ever learn and understand about the people they claimed to save? What success can the same Americans who once attested to be allies to Afghan women claim now?

Lifetimes after Sharbat Gula had her picture taken—her image stolen—by American photographer Steven McCurry, how many Americans know the name of one Afghan photographer?

Afghans, and Afghan women and girls in particular, do not need saving. They need—and deserve—understanding through multiple lenses and panoramas, and they need respect as individuals.

###

Author’s note: Afghan-led organizations to follow and support include Enabled Children’s Initiative and Art Lords, and the news agencies Ariana News, EtilaatRoz, Pajhwok News Agency, Tolo News, including the women-led Sahar Speaks and Rukhshana Media. This is not an exhaustive list.