Digby points to what she calls “a provocative piece” by Richard Florida at the Atlantic blog. She says it might explain “why the country is stuck and polarized”:

The connection between creative class states and the Democrats, and working class states with the Republicans is a clear break from the old pattern of the New Deal and post World War II. But it’s equally clear that both parties are constrained by their connections to long-held special interests. By paying excessive deference to the social conservatism and extreme anti-statism of its right fringe, the Republicans are unable to attract the creative class broadly, even though many of its members are drawn to its individualist ethos and fiscal conservatism.

Democrats, meanwhile, remain captive to the housing-finance-auto industrial complex which literally defined the old order. As the Cato Institute’s Brink Lindsey quipped some years ago, “Here, in the first decade of the 21st century, the rival ideologies of left and right are both pining for the ’50s. The only difference is that liberals want to work there, while conservatives want to go home there.” A sustained political realignment will only come about when one or the other of the two major parties is able to shuck off the interests that tie it to the past and develop an agenda that is in line with the future.

Unless and until that happens, the United States is likely to remain stalled at its current impasse, lurching between economic and political cycles while failing to address the deep structural challenges it faces — and unable to develop the much-needed reforms, new economic policies, and broad infrastructure investments required for a new round of sustained prosperity.

Does this mean that either the Republicans have to lose the social conservatives or Dems lose the unions in order for there to be a sustainable end to political gridlock? It’s worth a thought, says Digby.

I’m not so sure. Florida has an interesting thesis that what he calls “structural factors” may cause more of a swing in the 2010 elections than “cyclical factors” such as the economy. But I’m just not sure you can do that with pre-election polling data like he does.

More broadly, I think all of this talk about “creative class states” and “working class states” and this complex and that special interest misses the point. One of the major theses of my book Changing the Script is that we are stuck because there is a distinct lack of imagination on the part of our political leaders. They are unable or unwilling to question the basic premises that exert such control in our lives—consumerism, militarism, and so on—and so we see no meaningful change.

That might be the result of being captive to special interests, as Florida suggests. I happen to think it’s more basic. The system has simply run dry on the ability to see any kind of purpose or meaning in human life beyond working, shopping, and occasionally blowing up Muslims. (It used to be Commies.) So we see no real change.

And because nobody knows how to punch their way out of this bag, they start punching one another instead. Our quarrels, a wise man once said, are sometimes “simply a smokescreen to keep from facing the hard questions.”

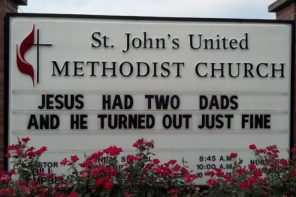

Perhaps it’s my own failing, but I can’t imagine where the vision would come from to reposition our system if not from God. Newness of life simply is not going to come about from within. Neither is real hope. That’s my story, and I’m sticking to it. You think what you like.

I do have to wonder, though, if the answer to Florida’s puzzle isn’t so much who the political parties relate to as how they relate. After all, social conservatives, unionists, and yes, even the rich deserve political representation, though not in today’s crapulent and apparently unchanging form. A new and more just way of being together might be just the ticket to getting the American political whale off the beach. All it would take would be a charismatic and articulate leader, who, along with a thoughtful and responsible political establishment, could summon the nation to a new understanding of common purpose…

Oh. Right. Never mind.