“All the world’s Muslims,” Richard Dawkins recently tweeted, “have fewer Nobel Prizes than Trinity College, Cambridge.” For good measure he sprinkled salt in the wound: “They did great things in the Middle Ages, though.” It happened so long ago, in internet time, that you might wonder the utility of a lengthy response. But in the great green country of Islamophobistan, where no argument goes unrecycled, what’s late one day might be on time another.

Unfortunately, too, many who responded to Dawkins’ tweet did no more than prove his point. By arguing for all that Islam had historically accomplished for science and technology, they were however unwittingly drawing attention to the great knowledge gap between the modern West and modern Muslims, or at least the modern Muslim-majority world, which is another reason to return to his tweet.

“What have you done recently for us?” Dawkins seemed to be asking. If the answer is nothing, does that mean Muslims don’t matter? (To justify the alienation, oppression, or killing of a person, you must first dehumanize him.) And you can do all kinds of things to folks who don’t matter. But Dawkins was not quite as clever as he supposed. Writing for The Guardian, Nesrine Malik proposed that if we:

insert pretty much any other group of people instead of “Muslims” and the statement would be true.

Malik addressed Dawkins directly:

You are comparing a specialised academic institution to an arbitrarily chosen group of people. Go on. Try it. All the world’s Chinese, all the world’s Indians, all the world’s lefthanded people, all the world’s cyclists.

It might make sense for Dawkins to think he can opine on the contributions of a civilization—though Trinity College would demand you have a degree in a subject before dismissing it altogether. It makes sense too for a scientist to think science is fair ground for such a fatwa. Though Dawkins would do his fans and foes a favor by taking this prospect of a multipolar world more seriously. Nobel Prizes are a largely Western affair. Most rankings, judgments and pronouncements on the “best of” this or the “worst of” that are absent Muslim considerations—all the more grating since one of four people in the world are Muslim.

Though, to be fair, the present Muslim world’s scientific (and other academic) achievements leave much to be desired; I will be the first to demand a sober appreciation of where and how Muslims have civilizationally depreciated. But I am also conscious that every argument has its flipside. Should Muslims focus on winning Nobel Prizes? What do Nobel Prizes measure, except an ‘abstracted’ science? And what does abstract science do for us? The number of nuclear bombs used by the West outweighs the number used by the entire planet. Muslims did not invent nuclear weapons, nor have they used them. (Let’s pray that stands.)

When Saddam Hussein was our ally, he unleashed chemical weapons on Kurds at Halabja, the only confirmed instance of a Muslim regime using chemical weapons. Even considering the possibility of Assad’s use of chemical weapons in his brutal war against his own people—supported by supposedly ‘Islamic’ actors, such as Iran and Hezbollah—still, nothing was invented. A Muslim world that lacks in groundbreaking scientific research also lacks in groundbreaking destructiveness; even in its pursuit of weapons of mass destruction, confirmed in Pakistan and suspected in Iran, the search has been derivative.

There are other senses in which the Muslim world, by and large, has not ‘excelled,’ and for that perhaps we should be grateful, not caustic. For you cannot claim the planet and eat it too. Nothing the Muslim world has accomplished can possibly compare to the harm done by Western technologies and modes of consumption. While China may recently have become the world’s biggest polluter, though not per capita, China was forced to be—else get conquered by the West. Don’t take my word for it, take Karl Marx’s:

The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilisation. The cheap prices of commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls, with which it forces the barbarians’ intensely obstinate hatred of foreigners to capitulate. It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilisation into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image.

On this measure, rather than express astonishment at Islam’s fall from a Middle Ages Golden Age, perhaps we should express happiness that Islam survived at all. Ask Australian Aborigines, Canadian First Nations, or our own American Indians what their countries think about their peoples’ pitiable record in Nobel Prizes. Yeah. Exactly. What countries? Once we step away from those societies, too, we see that Muslims who enter into different social systems and cultural politics can do quite well for themselves, while retaining religiosity.

Go to any university in America and you’ll come across a disproportionate number of Muslims. Before Dawkins can cry, ‘You succeed in the West but not the non-West!’—and thereby claim the superiority of the West he and I are both happily a part of—note that American Muslims have, on the whole, done much better than Western European Muslims. Whose fault is that? Why are Muslims succeeding culturally, creatively, and scientifically, in America, but not, say, at the same rate, in the United Kingdom or Germany?

Is it because those countries have done greater things in the past?

A dose of your own medicine.

To declare the Muslim world backwards on a Western scale is making an argument on assumptions you have yet to prove. Should Islam compete in science and technology? What does that even mean? Are the standards we set for ourselves organic to our own experience and true to our own values, or are they a continued imposition from without, an extension of what was once political hegemony but survives still as an assumption of superiority? Just imagine, after all, that the Muslim world should reach ‘Western standards,’ a world in which the average Easterner consumed as much as the average American.

There are more concerns, too. Just because you excel in the sciences doesn’t mean anything for your moral quality. The Soviet Union made tremendous leaps in science and technology, and actively contributed to the planet’s store of knowledge and capability. The first satellite in space. The first animal in space. The first human being in space. The same Soviet Union killed, in the name of scientific materialism and in the interests of atheism, millions upon millions of people. Persons of faith were especially targeted, by a regime that at its end had murdered more than any other. (Like Islamic extremism, its actual motives may have been quite different.)

But there is a fourth hole in this terrible Swiss Cheese of a tweet. What if you don’t produce good science because you can’t? Describing his (adopted) country’s powerfulness, the Anglo-French poet Hillaire Belloc quipped, ‘Whatever happens, we have got / The Maxim gun and they have not.’ Perhaps no more succinct definition of colonialism has been offered.

As Hamid Dabashi noted in Iran: A People Interrupted, most non-Westerners experienced the West at the wrong end of a gun. In this instance a machine gun. Which is an instance of great scientific accomplishment wedded to technological practice, or realization. Science doesn’t exist in a vacuum, even if Richard Dawkins does.

The Problem With Problems

At least part of the reason why the Muslim world, as opposed to certain Muslim-minority communities, suffers from a slide in technology, science, and even in learning its own tradition—if the Taliban are the students, we shudder to think who their teachers were—is because of political and social circumstances. We have little if any awareness of how regularly Muslim societies have been on the receiving end of violence, and I do not mean in the Middle Ages.

Let’s take the 16th century. The Ottomans had become Islam’s historically most powerful civilization. Along the Indian Ocean rim, as Engseng Ho argues in The Graves of Tarim, a new, peaceful, entirely non-militarized trade linked East Africa to China. (He’s at Duke University.) The artistic and aesthetic legacies from these periods speak for themselves. The Alhambra Palace in Granada, which so inspired Washington Irving. The Taj Mahal in Agra. The Blue Mosque in Istanbul. The wonderful domes of Isfahan.

But within a few centuries, all these lands were under foreign rule, their populations subjugated, and their cultural and religious assumptions shattered. Bernard Lewis asked: ‘What went wrong?’ Dawkins is at best a meager echo of such sentiments. Because if we ask what went wrong in the Muslim world, we must ask what went wrong everywhere. Africa, the Americas, Australia, East Asia—all were colonized or otherwise interfered with. The few Muslim governments that attempted to beat the West at its own game were quickly invaded and, albeit with great difficulty, put down.

Euthanized, as modernity likes to do to the ancient. The Albanian ruler of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, and Tipu Sultan of southern India, great nemesis of British ambitions in South Asia. One of the few countries to escape Western colonization was Japan. Is it, on balance, better that the Muslim world was largely colonized and fell behind, or would we have rather that, potentially, to complement Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan, a Muslim-majority state did its best impression of imperialism? The same Ottomans, in their twilight, were overrun by a nearly fascistic Committee of Union and Progress, whose treatment of the Armenians underlines my point.

Then, though the Muslim world achieved formal independence in the 20th century, this was but nominally sovereignty. These countries did not have the chance to develop their own institutions because of indigenous despotism and continuing external interference. For those who make the strange argument that “democracies do not attack each other,” consider Chile—not Muslim—and Iran—majority-Muslim. In both instances, the American government overthrew democratically elected leaders for fear of what they might do.

In 1979, Russia ‘intervened’ to save Afghanistan’s fractious Communist government, which gesture led to the deaths of nearly ten percent of Afghanistan’s population.

Afghanistan has still not recovered. Subsequently to this horrifying military intervention, Russia cracked down on a Chechen independence movement that emerged, plausibly enough, with the collapse of the brutal Soviet Empire. Tens of thousands killed, out of a population of just about a million. There were of course retaliatory Chechen attacks, but paling in comparison.

The Russian and Soviet expansion into the Caucasus eliminated whole peoples. There are, for example, no Ubykh speakers anymore. Most Circassians live in Turkey, Syria, Jordan, or anywhere but Cherkessia, which is their homeland. In a history of the past two centuries, one cannot worry much about the Muslim failure to ‘catch up to’ or copycat Western science, and never mind if this is a fundamentally Islamic goal—it wasn’t possible.

In the 1990’s, Russia supported radical Serbian nationalist Slobodan Milosevic, whose assistance to Croatian and Bosnian Serbs led to the massacre of tens of thousands. Muslims are, as we speak, the target of horrible persecution in Myanmar, a record of anti-Muslim bigotry that goes back almost to the founding of independent Burma, as it was then called. Their rights are denied in Xinjiang, properly East Turkestan, except they have no Dalai Lama-like figure to draw attention to their plight. (Who’s going to stand up to China anyway?)

Across the border, in Central Asia, Muslims remained ruled by Communist holdovers propped up by a Russia desperate to save its “near abroad”. Having seen what happened to Chechnya, it’s not surprising there’s little move to break free. There are, of course, sadly plenty of conflicts in which Muslims are involved, as aggressors, and worse still, plenty of Muslims who justify their sadism, barbarism and immorality in the name of Islam.

The best response to Richard Dawkins is not a history lesson, nor an appeal to specific verses, but a calm perusal of the newspaper. How can the Arab world, for example, technologically progress when its most populous state was kept under our thumb for decades? It is easy for Americans to forget that we supported Egypt’s dictator for thirty years, and happily welcomed Qaddafi back into ‘civilization’ when he realigned his policies with our own—not in the area of human rights, but ‘counterterrorism’. (And by ‘our’ I mean certain governments.)

The next best response to Dawkins will come, if it does at all, with how Muslims deal with a multipolar world, in which the West is not the only source of power and patronage. Thus freed—for a multipolar world offers more options—what will Muslims in the Muslim world spend their energies on? What will American and other Muslims contribute to their societies, their communities, and of course the planet at large? Do I pursue a career that makes me more money, or leaves the planet a better place? Do I use what I know about Islam to fight back against its misuse and at the same time misunderstanding of it?

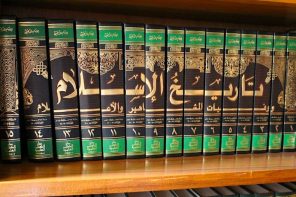

Once Muslims used to develop a language that looked out positively at the world, and inspired action in it, inflected by Islam but not limited to Muslims—or to any particular peoples. This was a great age, comparatively speaking, for Muslim culture, arts, aesthetics, sciences and learning, though we just call it the Middle Ages, which is kind of like the middle child, meaning it’s just something or someone you’d rather forget—which is par for the course for an adolescent contribution to the humanities by someone who not only should, but can know better.

I’m sure Dawkins can enroll in a course, take out a book, or even afford to buy a few. I’d be happy to make recommendations.