In the fall, I frequently teach a survey of American literature to the Civil War, and I end with one of the great wordsmiths of the nineteenth century: Abraham Lincoln. After the frantic gait of Emily Dickinson’s psychic drama and the spasmodic ecstasy of Walt Whitman, Lincoln gives the course a badly-needed sense of gravitas. Lincoln may have written speeches to save a nation, but they have also rescued my flailing syllabus on more than one occasion.

The Lincoln that I give my students is the Lincoln whom I acquired via Gary Wills, Harry V. Jaffa, and probably a host of other historians whose hagiography I have come to accept as my own. This is a Lincoln who shapes a secular creed for the United States, who canonizes the proclamation of equality in the Declaration of Independence as its central scripture, and who, in doing so, adds his own words to its gospel.

The genius, of Lincoln, I tell my students, was to look backward to the ideals of the Founding even while he ignored their failings. Motivated by a belief that the Union had an almost transcendent, divine power, Lincoln sought to craft a history that he believed could carry the nation into the future as a reunited whole. His most brilliant rhetoric—the dedication of the Gettysburg Cemetery and his second inaugural address—calls upon Americans to attend to the “unfinished work” of this enterprise, and suggest that those who have died in the Civil War demand nothing less. This entreaty to “finish the work we are in” plays well as the closing act of the semester. It is, if I may say so, a pretty good lecture.

I have been thinking about the Lincoln-of-the-secular-creed during this last week, the bicentennial of his birth. The United States may need a reenactment of the New Deal, but America is also in a moment of Lincoln-mania cultivated, with great skill, by our president. I’m still working my way through all of the Obama-Lincoln articles in the popular media—and I am waiting for the scholarly presses to begin churning out articles and books on the phenomenon. If only I had been prescient enough to record my own fine oratory, I might be able to document that I noted an affinity while teaching the Lincoln class years ago, after the 2004 Democratic convention but before Obama began his improbable presidential run. The press loved Barack Obama, I simply said, because he understood something that Lincoln understood—and that too many politicians from all political persuasions had forgotten: the English language can be a beautiful thing.

Of course, the affinity is deeper. Obama would recognize the Lincoln of my lecture, who had an abiding faith in the progress of humanity, the spread of equality, and the ability of Americans to work toward a common purpose. Surely, this is the mantle that Obama hopes to claim. Our President should also understand, though, that Lincoln did not always speak the truth directly, that his rhetoric sometimes outstripped the reality of the divided nation in which he lived.

Lincoln, after all, was widely reviled during his own presidency, and even for decades afterward his legacy in the United States was deeply divisive. As Barry Schwartz—a sociologist who has studied the evolution of Lincoln’s image over time—has shown, it was not until the centenary of his birth, some one hundred years ago, that the sixteenth president was fully embraced by the nation he labored to save.

So when Lincoln claimed, in his second inaugural, that both sides in the US Civil War “read the same Bible and pray to the same God,” he was hardly speaking the truth, particularly on the latter count. As he noted, many were praying to a God that allowed them to wring “their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces.” Many other Americans were praying to a God that they believed would deliver them from the hell of that slavery. The prayers would change after Lincoln’s death, but the divisions would remain long after. One way of understanding the Civil Rights Movement of the twentieth century is to consider that it was nothing less than a continuation of a long theological struggle over whose God would prevail.

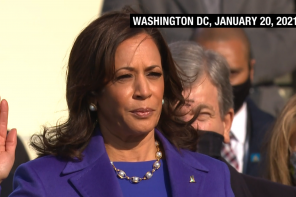

Is that struggle over? Speaking in the rotunda of the US Capitol on Thursday, as part of the celebration of Lincoln’s bicentennial, President Obama seemed to recall the words of that second inagural. He asked that Americans remember that they are debating the issues of our time “as servants to the same flag, as representatives of the same people, and as stakeholders in a common future.” This is easier to compass than the possibility that we might be reading the same scripture and praying to the same God.

However, I hope that President Obama can imagine that we may not, in fact, be servants to the same flag—or at least servants who agree on what that flag may mean. No matter what he said publicly, Lincoln seemed to understand that possibility, and he was ready for the deep struggle that his own creed of justice demanded. That struggle cost him not only his life, but also his national reputation for the following half-century. Let the cost of the battle be much less dear for our current president, but let him be equally prepared for the fight.