In the second act of William Shakespeare’s Henry V, the bawdy barmaid Mistress Quickly delivers a eulogy for one of the playwright’s most immediate, modern, and visceral of characters. Speaking of Sir John Falstaff, who drank, thieved, embellished, and joked across both Henry IV Part 1 and Part II, the proprietor of the Boar’s Head Inn assures us “Nay, sure, he’s not in hell! He’s in Arthur’s bosom, if ever man went to Arthur’s bosom.” Mistress Quickly recounts that, as Falstaff approached the end of his life, “His nose was as sharp as a pen, and he talked of green fields.”

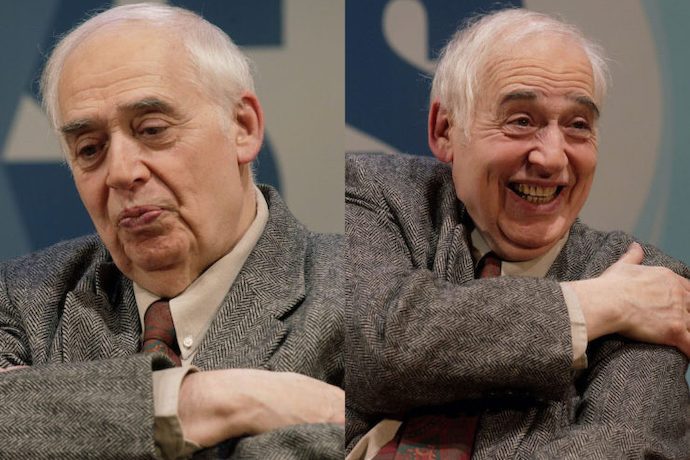

An appropriate image and metaphor, the sharp pen, for America’s most famous literary scholar Harold Bloom was welcomed into Arthur’s bosom this week at the age of 89 in New Haven, Connecticut; a man who, in his erudite yet disheveled, avuncular yet cutting, radical yet deeply conservative, way had always configured himself as the Falstaff of criticism. Bloom said of Falstaff that he was the “grandest character in all of Shakespeare,” which was saying something since the critic also maintained that Shakespeare, more than just being a great (or the greatest) of writers, had actually invented what it means to be human.

Such grandiose pronouncements of Bloom’s, things like when he inveighed against the “recent politics of multiculturalism” and the “schools of resentment,” which he associated with literary theories indebted to feminism, Black studies, and queer studies, made him the most famous literary scholar in the United States. As Sterling Professor of the Humanities at Yale University since 1955, Bloom finished his last class just days before he died which underscores his commitment to literature. Say what you will about his conservative aesthetics, his valorization of the transcendence of poetry was many things, but an act it was not.

Often this love of literature—which anyone willing to go through the frustration, difficulty and insecurity of a PhD shares with him, even if Bloom sometimes denied those of us that similarity in vocation—could manifest itself with denunciations of his colleagues who were as “fresh rushes of academic lemmings” obsessed with the “political responsibilities of the critic.” That became Bloom’s role, the traditionalist bemoaning all of these fashionable theorists in the academy, while he alone remained true to Victorian critic Matthew Arnold’s contention that literary study must be contemplation of the “best that has been thought and said in the world.”

There is, of course, an irony to this, because when Bloom began his doctoral studies he was within the radical camp, the “Yale School” of critics like Paul de Man and Geoffrey Hartman who were strongly indebted to the deconstruction philosophy of Jacques Derrida. Several currents of Blooms’ “School of Resentment” were also in the stead of Derrida and other French theorists, but over his career the professor seemingly moved away from his earlier, innovative arguments in favor of his later writings which were obsessively focused on literary greatness, including how to identify it and how to categorize it. Such issues of canonicity, when they take the idea that rational, objective standards of greatness are possible (or even desirable) aren’t just elitist, they aren’t necessarily even that interesting. More importantly, such concerns are often more about furthering an elitist status quo rather than interpreting literature, as Bloom’s ham-handed readings of brilliant writers from Adrienne Rich to Maya Angelou will testify to. Even his denunciations of J.K. Rowling evidenced a certain turning away from that which spoke to people, an abdication of Roman playwright Terrence’s contention that “I am human; I let nothing which is human be foreign to me.”

“We need to teach more selectively,” Bloom wrote in The Western Canon, and no doubt the task of selection was given to the sort of men who could become the Sterling Professor of the Humanities at Yale University. That this selection was frequently done with an eye towards bolstering those old racial and gender hierarchies goes without saying. Bloom might not have had much use for talking about such issues, but that doesn’t mean that everybody else didn’t. When viewed in tandem with the credible allegations about him concerning sexual harassment, the overall picture of the man is made all the more problematic and complicated. His critical traditionalism often had readers confusing him with that “Other Bloom,” Alan, whose neo-conservative treatise The Closing of the American Mind made similar arguments, though our Bloom’s avowed socialist politics made him embarrassed to be included with such company. It’s easy to see why the public would understand Bloom as a conservative, for in dozens of books like Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human, How to Read and Why, and The Western Canon, that’s precisely what he appeared as.

A certain shame to that, because for a man clearly so brilliant, so capable of writing that intelligently, and who in his prime could produce readings of literature that the rest of us could only aspire to, there’s a shadow list of his publications that go far beyond the baseball card collecting of The Western Canon. Bloom probably wouldn’t have seen the ruptures between his earlier and later work, but if there’s one thing that unites, say, The Anxiety of Influence and his later work, it was a keen religious vision.

If in a hundred years people are still reading (and Bloom prayed that they would be), then I hope that they’re still reading The Anxiety of Influence, A Map of Misreading, Kabbalah and Criticism, Agon: Towards a Theory of Revisionism, Ruin the Sacred Truths: From the Bible to the Present, The Book of J, and The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation. I may have come off earlier as intemperate toward Bloom, but it would be a mistake to think that I don’t respect him. I positively valorize Harold Bloom.

As he notes in The Anxiety of Influence “There must be agon, a struggle for supremacy,” and in that regard all younger critics have been in conflict with Bloom for decades. That aforementioned listing of studies is astounding; that it gets lost in the (always incredibly well written) dross is its own small tragedy. Because for all that Bloom got wrong about theory and the state of the discipline (and he was very often wrong about it), he was correct in his contention that the sometimes godlessness of the field was a critical detriment, and that “A nation obsessed with religion rather desperately needs a religious criticism,” as he noted in The American Religion.

The works listed above, and more besides, constitute a remarkable syllabus of theologically inflected literary criticism, drawing from sources as diverse as Kabbalah and Gnosticism, to provide readings of canonical literature frequently more radical than anything from the tired deconstructionist pens. There are those who produced similar work; Frank Kermode and Northrop Frye were certainly brilliant religiously inflected critics, and today Terry Eagleton continues in their theological stead. But Bloom, in his sheer expansiveness, was our last great religiously inflected critic. If he sometimes made literature itself a religion, that was no major sin, for he understood that there is no reading or interpretation that doesn’t find its origins in exegesis. He writes that kabbalah is the “ultimate model for Western revisionism from the Renaissance to the present,” and this is more generally true for all forms of scriptural interpretation as related to literary criticism.

If Bloom was right about any one thing, it was this: literature is a form of sacred writ, and those in its stead are its monks. Perhaps, with our minds towards the transcendent, we too may depart as Falstaff, who may as well be turning pages when he does “fumble with the sheets and play with flowers/and smile upon his fingers end.”