Given the history of opposition to the ordination of women, it may come as little surprise to learn that mainline Protestant women clergy are some of the strongest voices supporting marginalized communities and prioritizing religious pluralism. Across social issues and concerns, women clergy are often the first to speak up publicly, influencing not only their congregants but also other already left-of-center male clergy. Both history and contemporary research can help us understand the influence of women clergy on their denominations, and to a larger extent, the religious and social fabric of our country.

Sojourner Truth. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Despite the legacy of opposition, notable women preachers have existed throughout American history. This distinguished list includes Sojourner Truth, the formerly enslaved abolitionist who became an outspoken advocate for racial justice and for women’s rights, Antoinette Brown Blackwell, who began preaching in her family’s Rochester Congregationalist Church as a child in the 1830s (and who became the first woman to be ordained by a major Protestant denomination), and evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson, who established the Angelus Temple in Los Angeles before the Great Depression, which attracted millions of visitors and whose charismatic preaching style made her one of the country’s most famous women. Yet, despite these early trailblazers, widespread debate about women’s ordination in American mainline Protestant denominations didn’t begin in earnest until the mid-twentieth century.

In the 1950s, the United Methodist Church became the first major mainline Protestant denomination to allow women pastors. By the late 1970s, in part a reaction to the second wave of feminism, each of the seven largest mainline Protestant denominations had begun to welcome women to the ranks of the ordained.

Although women still represent a minority of ordained mainline clergy today, their presence has grown substantially since they first entered the pulpit in the 50s, 60s, and 70s. In 1978, fewer than 3 percent of clergy were women, but by 2017, their numbers had grown to approximately one-third of ordained clergy in the mainline denominations. Despite these gains, women clergy still remained less likely to serve as lead or senior pastors than their male counterparts.

My 2005 book, Women With a Mission: Religion, Gender, and the Politics of Women Clergy (co-authored with Sue E.S. Crawford and Laura R. Olson), examined the political priorities and behaviors of women clergy, including Protestant pastors and Jewish rabbis, several decades ago. We found that many women clergy undertook as part of their religious calling a commitment to helping the disadvantaged and marginalized, through preaching, community activism, and political organizing. Their identities as women in a male-dominated profession, and a larger commitment to women’s equality, also profoundly shaped their political views and habits.

Compared with male clergy in major mainline Protestant denominations, our research (with political scientist John C. Green) also found that women clergy identified as more Democratic and held more liberal policy views. Although we found that male clergy held more liberal positions in comparison to men in the general population, a significant gender gap appeared on a variety of policy attitudes, including cultural issues such as abortion and LGBTQ rights.

In a survey released this fall, my organization PRRI found once again that mainline Protestant clergy overall are more politically progressive and identify as more Democratic than their parishioners. But what an initial analysis failed to note was the significant gender gap that continues to shape and define the political identities and opinions of mainline clergy today.

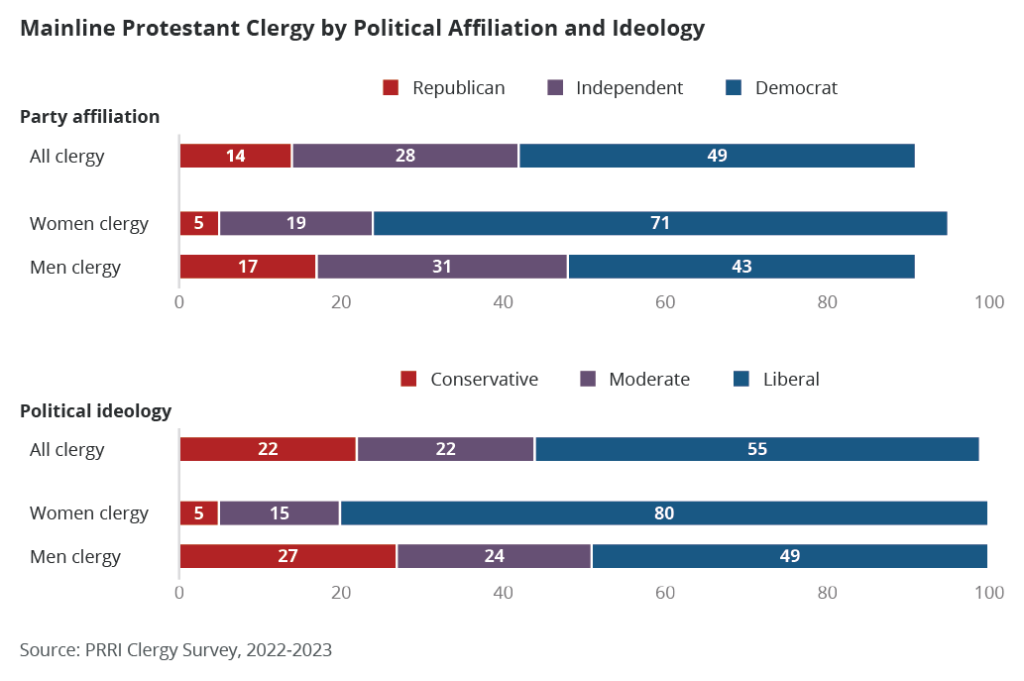

Unpacking clergy party affiliation and ideology

In a new analysis of this survey, women clergy are far more likely than men clergy to identify as members of the Democratic Party (71% vs. 43%, respectively) and as liberal (80% vs. 49%, respectively). While only a relatively small minority of male clergy identify as Republican, they’re more than three times as likely to do so than women clergy (17% vs. 5%, respectively). The gender gap among clergy identifying as conservative is even starker, with men more than five times as likely as women to claim a conservative identification (27% vs. 5%).

Support for LGBTQ rights

In 2008, PRRI found that mainline women clergy were more supportive of marriage equality than their male counterparts before the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision made it the national law of the land. Although the question was worded differently—we gave clergy in that survey the option to indicate support for allowing gay couples to be married (“same-sex marriage”), support for forming civil unions but not to marry, or opposition to any legal recognition for gay couples—a solid majority of women clergy (58%) supported marriage equality, compared with just 27% of men clergy; additionally, 28% of women clergy supported the civil unions option, compared with 33% of men clergy.

In a post-Obergefell world, the vast majority of mainline clergy (79%) now support marriage equality, according to our more recent clergy survey. Yet, gender differences remain. Support for marriage equality is nearly universal among women clergy members (93%), while only 75% of men clergy members say the same.

Those gender gaps among mainline clergy extend to broader protections for LGBTQ Americans. Today, women clergy overwhelmingly (96%) favor laws that would protect gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people against discrimination in jobs, public accommodations, and housing, compared with 88% of men clergy. Women clergy (86%) today are also more likely than men (64%) to oppose allowing a small business owner to refuse, on the basis of their beliefs, to provide products or services to LGBTQ people.

Abortion and gender attitudes

In PRRI’s 2008 survey, mainline clergy were more divided over abortion, with 51% of clergy supporting abortion’s legality in all or most cases, compared with 49% of clergy opposing abortion’s legality in all or most cases. However, more than three in four women clergy (77%) supported abortion’s legality, compared with fewer than half of men clergy (44%).

While the more recent mainline clergy survey didn’t ask about abortion directly, we did ask about the overturn of Roe v. Wade, which provides insight into their attitudes about abortion. Unsurprisingly, a deep gender gap on abortion attitudes remains: while most men clergy opposed the overturn of Roe (69%), nearly all women clergy (91%) opposed the decision.

PRRI’s most recent survey also finds that while most mainline clergy reject the idea that American society as a whole has become “too soft and feminine,” women clergy do so at higher rates than men clergy, 97% versus 80%, respectively.

Cultural identity and religious pluralism

Maintaining the trend, women clergy members are also more likely than male clergy to embrace religious pluralism. For instance, our most recent clergy survey found that 62% of women clergy think that the US would benefit from having more elected leaders who follow religions other than Christianity or who are not religious, compared with 43% of their male counterparts.

Moreover, male clergy are substantially more likely than women clergy to agree that “America is in danger of losing its culture and identity” (40% vs. 24%).

Academic research has long found a clergy-laity gap among the White mainline Protestant traditions when it comes to political and policy views, and PRRI’s most recent survey continues to document this trend. But our survey also finds that another, often overlooked, gap characterizes attitudes among clergy as well.

While evangelicals are the focus of so much discussion concerning religion and politics, close to 14 percent of Americans are White, non-evangelical/Protestants at last count. And women clergy in the mainline tradition are not only the strongest allies of many marginalized groups in our culture, but they also prioritize religious pluralism at rates higher than their largely already left-of-center male colleagues. The feminization of religious leadership may help explain why we’re seeing the increasingly progressive direction of many mainline Protestant denominations today—and it may well provide a strong hint as to why evangelical denominations like the Southern Baptist Convention are reluctant to include women at all levels of leadership.