If religious kitsch is a guilty pleasure, one of my favorite indulgences is a graphic that depicts a school of ichthus—the simple outline of a fish that is was an early symbol for followers of Christ—with a contemporary “evangellyfish” swimming in the opposite direction.

The caption reads, simply, “Go against the flow.”

The 2014 U.S. Religious Landscape Study, which is being rolled out in a series of reports this year, depicts a deep shift in how Americans identify (or don’t) with religion. It’s tempting to approach the latest report, and those to follow, with attention grabbing headlines that portray the complex statistics as a simplistic counting of which way the proverbial “fish” are swimming.

To do so would be a grand mistake.

While fluctuating statistics about how American adults affiliate religiously are important, the greatest insight the latest report provides is about the water in which we are swimming.

A deeper dive into related polling data indicates that the greatest shift right now might not be in attitudes toward religion or religiously related behavior, but instead about default assumptions regarding what it means to choose (or not to choose) to affiliate religiously.

A prime example of this shift might be the structure of a key question in the Pew survey itself.

The Big Question

In Appendix C, a section many readers might have overlooked, the researchers note that, “all major religion surveys find that the unaffiliated share of the U.S. population (the percentage of religious ‘nones’) is growing rapidly.” Still, Pew’s study has higher rates for this population than any of these other surveys.

In 2014, for example, the National Opinion Research Council’s General Social Survey (GSS) put the proportion of “nones” at 21 percent of the population, while Trinity College’s American Religion Identification Survey (ARIS) counted “nones” as 20 percent of the population in 2012, compared to Pew’s own estimates of 23 percent.

While there may be many reasons for these discrepancies, the Pew researchers chose to explore just one: how the big question of affiliation is asked.

The GSS queries, “What is your religious preference? Is it Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, some other religion, or no religion?” while ARIS asks, “What is your religion, if any?”

The Pew ask a different question: “What is your present religion, if any? Are you Protestant, Roman Catholic, Mormon, Orthodox such as Greek or Russian Orthodox, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, atheist, agnostic, something else, or nothing in particular?”

Pews researchers said they believe, “by explicitly offering respondents the chance to identify as atheist, agnostic or ‘nothing in particular,’ the Religious Landscape Study question may make it easier for marginally religious people who once thought of themselves as Catholics, Protestants or members of another religious group to identify as religious ‘nones.’”

As currently worded, the questions in other surveys assume that a respondent will identify as religious unless they explicitly opt out. The Pew study claims, and I believe correctly so, that by offering additional answer options up front, respondents feel a greater sense of freedom to answer the polling questions accurately. People who previously would have felt a conscious or subconscious pressure to identify with a religion are less likely to do so.

In attempting to quantify how (and how many) Americans identify religiously today, what we’re really asking is something deeper than how many people feel like they should tell a pollster that they are religious. The more meaningful answers arise when a set of attitudes and behaviors are correlated with a religious identification.

We want to know that when people say they are Catholic, Hindu, evangelical or Jewish that those identifications mean something about how those people act and think about the world and others.

This does not mean the “rise of the nones” as detailed in this report is insignificant. Far from it. Such changes in declared identification have huge implications for society today. And yet the import and meaning of these changes are likely more nuanced than how they often are portrayed.

A mouse pad decorated with a school of ancient “ichthus” Christian symbols (and a contemporary “evangellyfish” headed in the opposite direction). Image via Zazzle.com.

A few examples:

Self-reported church attendance is roughly the same today as in the 1940’s and did not change significantly during the time of these reports. According to a Gallup survey released in December 2013, “Nearly four in 10 Americans report that they attended religious services in the past seven days. Americans’ report of their weekly church attendance has varied over the years, but it is close now to where it was in 1940 and 1950.” That same survey showed, “Americans’ assessment of the importance of religion in their lives generally has been stable over the past four decades.”

As Pew continues to release its data over the course of the coming year, it might well find more changes than Gallup has in these other measures of religiosity, but the relative stability of these other markers do not make a case for a sudden and swift collapse of Christianity in America.

Ed Stetzer, who leads the Southern Baptist Convention-affiliated Lifeway Research has argued that these numbers indicate a redefining of Christianity in which those who had been marginal or nominal Christians all along feel a greater comfort in simply reporting what was true about them all along, that they are unaffiliated.

The percentage of American adults who identify as “born again” or evangelical increased over the timeline of these studies. What is even more interesting than the factoid itself is that it occurred while the percentage of American adults who identify with an evangelical institution has declined.

This apparent contradiction could be explained again by the theory that more of those who were previously marginally affiliated are simply being more honest with pollsters about that fact. In contrast, being asked if you are “born again” is very different. For many people this refers to a personally transformational experience not an institutional affiliation.

Following such a line of reasoning might mean we are seeing an uptick in the number of American’s who will report a life-changing Christian experience while simultaneously being less likely to identify with any particular Christian institution. This raises questions about the complicated relationship between Americans and their willingness to affiliate with large institutions (religious and otherwise) in general.

The rate of decline in affiliation for America’s two largest protestant denominations—the Southern Baptist Convention (evangelical) and the United Methodist Church (mainline)—is roughly the same.

Declension among mainline denominations has been widely reported for some time and for good reason. From 2007 to 2014 the number of Americans who affiliate with a mainline denomination has dropped from 18.1 percent to 14.7 percent. As widely reported, the UMC (the largest mainline denomination) declined by 1.5 percent during that period. Less widely reported, however, is that the Southern Baptist Convention’s population also dropped 1.4 percent during the same period.

Even less widely known is that if you look at the 10 largest protestant denominations in the country, the only one that grew during that time (at a rate of .3 percent) was the American Baptist Churches USA, which is classified as a mainline denomination.

Growth for evangelical institutions has occurred almost entirely under the auspices of the ambiguous classification of “evangelical non-denominational”. These trends in Protestantism coupled with the significant decline among those who identify as Catholic (from 23.9 percent to 20.8 percent between 2007 to 2014) indicate a deep ambivalence to the nation’s largest religious institutions.

Because of the size and notoriety of America’s largest denominations, identifying with them carries more cultural baggage than lesser known institutions. It means more in our culture to identify as, say, Catholic, Southern Baptist, or Methodist than it does to affiliate with a more obscure religious institution. This fact might contribute to the reality that those who continue to choose to affiliate as Christian are less likely to identify with the groups that have been the largest players in American Christianity.

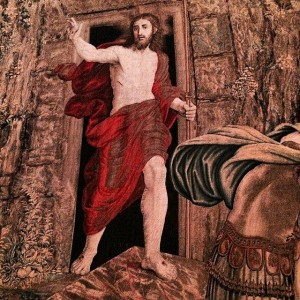

Detail of a tapestry depicting Christ emerging from the tomb from the Vatican museums. Photo by Cathleen Falsani.

The Decline of Christendom

Obviously, from the numbers and the tales they tell, American Christianity is hardly experiencing a Renaissance. But the rise of the “nones” does not equal its wide-scale collapse, either.

A better description might be that we are witnessing the decline of “Christendom.”

In this sense” Christendom” refers to the broader assumptions we imbibe, often without being fully aware, as a result of the influence of Christianity on the culture as a whole. Under Christendom, many people assumed an affiliation with Christianity unless there was a reason to do otherwise.

Under such a rubric, the rise of the nones could be interpreted primarily as a shift in cultural assumptions—that people are more likely to say “nothing in particular” unless they have a good reason to identify otherwise when asked about their religious predilections.

Pew’s forthcoming reports will provide greater depth to understanding the nature and significance of these changes. The release of these initial numbers makes one thing clear: the water is changing, and fast.