The cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter is well known for his pioneering work on artificial intelligence, his brilliant writing about language and identity, and for his classic, Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Gödel, Escher, Bach.

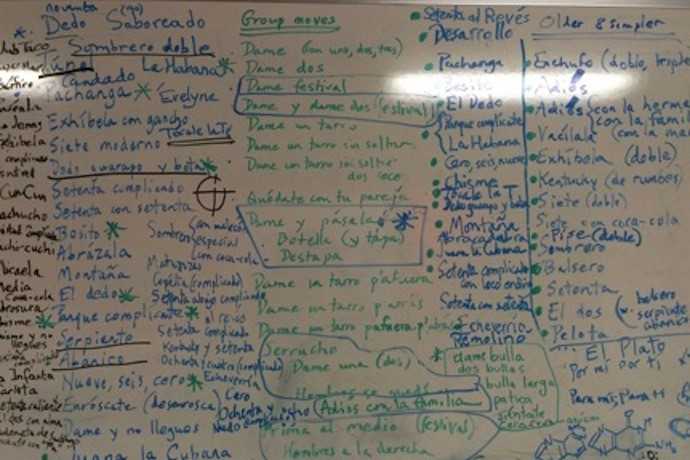

He is not known for salsa dancing. Which is why I was surprised, upon being invited to dinner at his home last month, to find myself eating pizza and sherbet in Douglas Hofstadter’s salsa room, complete with red walls, a black-and-white checkered floor, and a dry-erase board on which the cognitive scientist had scrawled hundreds of Spanish phrases. Hofstadter explained to his guests (the students in a seminar on sexist language) that these phrases were all salsa moves. He’s been practicing them with a small group, every Sunday, for two hours.

Hofstadter took up salsa five years ago while on sabbatical in Paris, a pursuit he explains in terms of simple admiration. Having envied those who could appear so cool and composed on the dance floor, while also totally virtuosic and precise in their movements, he decided to learn.

This fascination with salsa feels continuous with his work in cognitive science. Hofstadter’s persistence is legendary; he’s preoccupied with discovering the structure and essence of the mind and human creativity. He picks systems apart and then rebuilds them as unified wholes, whether those systems are language, the cognitive process, or dance.

In writing, Hofstadter’s interests range from artificial intelligence, mathematical proof, and musical composition, to language, the self, analogy, and cognition. His first and best-known book, Gödel, Escher, Bach, is an imaginative, genre-spanning exploration of the philosophical underpinnings of artificial intelligence. He followed that work with The Mind’s I, co-written with Daniel Dennett, in which the two cognitive scientists reflect on the complexity and strangeness of the concept of self or “I” as articulated across works of world literature and philosophy.

Few people have thought as creatively about the relationship between mathematics, patterns, language, and identity—in other words, about the science of the self. And Hofstadter himself has studied, and lived out, his own tangled “I”—as a thinker, an author, and someone with a modest measure of celebrity.

Hofstadter turned 70 this past February. Curious about the “I” of Hofstadter at 70, and the relationship between the author and the halo of his public persona, I sat down with him in the Salsa Room to discuss some of the common threads of his life and work. The result is the interview-cum-narrative transcribed below.

This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

On Writing Systems and Whirly Art:

You seem to be always striving to deeply understand complex things like dance and language. We’re sitting by a whiteboard on which you’ve written the names of probably hundreds of salsa moves. It’s clear that you want to break these things down, but you also want to build them back into a whole, into something that is essentially human and creative. I’m thinking of the figures in Gödel, Escher, Bach illustrating reductionism and holism—

Oh, yeah, I think I know what you’re talking about—different levels of description, as in the amusing HOLISM/REDUCTIONISM figure, which has structure on four different levels. That kind of thing is certainly a very major theme in my life and in my writings. But actually, the figure in GEB that I thought you were going to bring up is much closer to salsa, in a way. It’s the figure that’s filled with samples of beautiful curvilinear writing systems, like Sinhalese, Tamil, Bengali, Thai, and so forth. When I was in my late teens, the mystery of these languages was indescribable, the idea that these curves contained or represented sounds. These very fanciful shapes that stretched out for long distances were ideas. It was very magical and mystifying to me.*

I can say it—I can mouth it—but I can’t feel it the way I felt it then. It launched my quest for creating designs. I wanted to compose visual fugues, which my sister called “Whirly Art.” I remember the first one I ever did was sitting on an airplane crossing the Atlantic on the back of a letter pad. I had a pencil, and I drew three horizontal lines, and that was the theme of the fugue. And I drew three horizontal lines higher up but to the right and that was the second voice entering. And then I drew some other stuff interacting with it, and I moved from left to right across the page, so the fugue was a very, very short thing visually. But I had done something which was to make a visual thing, that I called a fugue, [but] that wasn’t music. That was the germ of one side of this art form.

The other side was that I was in love with these forms from Sinhalese, Tamil, and other languages. My hand would start to trace curves that came from those alphabets. I didn’t know what they meant. The shapes became part of me, but the point was that I just would start improvising using elements of the shapes. They were no longer letters. And then these two things merged. I started drawing fugues, and instead of having just three parallel lines, which is a pretty boring theme for a fugue, I would have some kind of intricate shape and this intricate shape would then be repeated. I would have different voices, and the voices would intermingle, would have harmony in the way they interacted visually with each other. They would go down long strips of paper and sometimes could be five feet long, fifteen feet long, twenty feet long, all improvised. This became an obsession of mine.

On Salsa and Fugue:

Salsa could be said to have something in common with these alphabets and these fugues. Again it’s the sense of curvilinear motion in space, improvised, unexpected, all the time catching you off-guard, surprising you forever. In Whirly Art the idea was to do very long lines. Sometimes in salsa you can do things that have the quality of being like a very long line, though normally when you learn salsa you learn it in moves. That is, you’re taught a move, sombrero, and it lasts ten seconds, twelve seconds, it depends on how fast the music is. But it’s a chunk. And then you learn another move, balsero, which is sort of sombrero twice, and then besito is another one, and then after that there’s something called exhíbela.

After exhíbela, there’s something called, well, we don’t have a name for it, but it’s sort of balsero reversed, then there’s barrel roll, then abánico, then enchufe. Now if you put those all together, so balsero, besito, sombrero, exhíbela, backwards balsero, barrel roll, abánico, and enchufe, it’s all one thing, called bebé. If somebody doesn’t know bebé, they will think that you’re just improvising this long thing.

It’s a very long, long extended seamless thing. Although you can see substructure, there is no stopping point. It’s flowing the whole time, and that’s very closely related to Whirly Art. It’s very closely related to my passion for languages, to my passion for music, to my passion for fugues, for structure, for symmetry, and it goes on.

On Love, Shame and Chopin:

See, this is the story of my life. Things come from a mixture of profound love and profound shame. In my case, the love that was infinitely profound was for music, for fugues, and for other kinds of classical music. In my teenage years I was profoundly involved with music in this way that just defies description.

But at the same time there was this sense of inferiority and shame and inability and incompetence because I tried to learn a particular Chopin etude that was perhaps the greatest piece ever written, from my viewpoint. And it was too hard for me. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t learn it. I suspect that if I had spent ten years trying to learn the seven or eight pages of music that it is, I might have been able to learn it in ten years. But that’s not sensible.

I felt humiliated, at least humbled, by my own limitations. Many music students learn all of the Chopin etudes, twenty-seven of them. I eventually did learn some Chopin etudes, but that one I’ll never be able to learn. My point is I was driven by this passion but also by a sense of inability.

In my teenage years I didn’t understand the depth to which one must dedicate oneself in music if one wants to become very good. I admired composers beyond perhaps anyone else. They were my biggest heroes. I felt if I couldn’t be a composer, I was a failure. It’s like I had to compose. Since I wasn’t at that time playing piano at all, I channeled all this musical passion into drawing.

Then with GEB, I channeled it in the direction of dialogues. It was like the love of fugue and canon and structure reasserted itself in a new domain, in my case. It came out spontaneously in this amazingly self-driven, self-propelled way.

Hofstadter and “I”

Your books often focus on the self, or “I”. The style you write in is often narrative, and you intersperse discussion of the self as a construct with personal anecdotes from your own life. So it seems that while you have an academic interest in the self, your books also simultaneously narrate your own self to some degree. It seems appropriate that the first story you included in The Mind’s I was “Borges and I” by Jorge Luis Borges, which looks at the relationship between an author and his work.

“His”?

“His” being Borges’s – a specific “he” there.

I think this is the contaminated generic “he.”

It is. Though I think it came out with a sort of traditional generic “he” sound to it.

Borges and I contaminated it.

I’d like to know what your feeling is about your relationship with your written work. As I’m sure you know, many students take your courses because they’ve read your books.

Well, it’s interesting; the other day some students mentioned this when I asked them why they took my course. They went around the table, and they were all saying, “oh I took this course because I heard of Douglas Hofstadter.” They didn’t all say that, but golly, 90% of them did.

I mean, it’s flattering, but I don’t really know if I want to be flattered. I am just more interested in ideas. The truth is, my two kids, Danny and Monica, are not readers of my books. I’m flattered that Danny decided to read Surfaces and Essences this year and he’s twenty-seven now. It’s only half mine, but it’s the first book of mine that he has tackled. Monica, who’s twenty-three, may have read one book.

The point is, my kids know I’ve written books, but it’s not like they think of their dad in terms of his books. They think of me in terms of what you would expect, everyday interactions. The food that I fixed for them when they were growing up, the stories I read to them, that we spoke Italian at home, that I took them to Italy, that we ran off to California all the time. Those are the things that made my relationship with them.

I’ve been very blessed by the fact that my books have brought me into contact with a remarkable, wonderful set of people. That’s one of the great things that have come to me through having written books—that I’ve met people who otherwise I wouldn’t have met. I wouldn’t have known these people. And I feel that’s a great, lucky thing. Those people initially knew me as the author of a book – but luckily they go way, way beyond that.

On Human Connection: A Letter to Alexander Jenner

This is a blow-up of a record cover from 1950 of Chopin’s Etudes, Opus 25. Alexander Jenner recorded this when he was twenty. In a certain sense, this is the most important record of my entire life, this first classical record that I ever heard. It happened, and just changed my entire life. Completely.

One day I said, “Where is Alexander Jenner, is he still alive?” So I looked up his name. There was a site devoted to people who played on this label, Remington Records. It had bios of various people and didn’t mention any death date. I wrote to the person in Holland who put this site together and said, “Do you happen to know how to reach Alexander Jenner, is he still alive?” He gave me a postal address for Jenner in Vienna, so I wrote a four-page letter telling him how much of an impact this record had had on my life. I kissed the envelope when I put it in the mailbox. At the last moment, just before sealing the envelope, I scribbled a tiny P.S. that said, “By the way, if you use email, here’s my email address.”

When I came back after two weeks there was an email from Alexander Jenner. And the first thing he said was, “Dear Professor Hofstadter, it was such a pleasure to receive your letter. We were just talking about you the other day.” It was like, WHOA! Just so twisted. Of course it could only happen because I’d written books. He said, “We were walking down the street in Vienna and there was a plaque that said ‘Gödel lived here,’ and my friends and I started talking about Gödel, Escher, Bach.”

It’s just too weird. He knew about me, but he didn’t know that I knew about him. That he had been so pivotal in my life. And luckily, I reached him.

On Radio Warsaw:

I can tell you another story that has to do with Chopin. This was before I had written any books. I had sketched GEB, but I by no means had finished it. I went off to Germany to work on my PhD thesis with my advisor, in the town of Regensburg near Munich. And it was a very lonely time because I didn’t know anyone there. I would turn on the radio and Radio Warsaw would play something at exactly midnight, that would go, “Hello, this is Radio Warsaw calling… Ici Radio Varsovie… This is the time for our nightly Chopin broadcast.” And it was a half an hour of Chopin music. I would listen every night religiously to this thing as it faded in and out. I taped it, every night.

At one point a physicist I knew in Warsaw wrote me and said, “Would you like to come and visit and give a talk on your research.” The idea of going to Poland, Chopin’s country and also the country of my grandparents excited me. I said I’d love to, and we set it up for March of 1975. I ran up immediately to the bookstore in downtown Regensburg and bought a grammar of Polish, and I went through it from head to toe and did all the exercises, and I got extremely excited about it. I was playing piano at the university. I would spend an hour a day practicing various pieces. It was all extremely intense. Just amazing. And so the day came when I was leaving. I could barely sleep. I took the train from Regensburg across the Iron Curtain.

So there we are in Warsaw, I’m with Marek Demianski, this physicist. We did a lot of Chopin things, including going out to Chopin’s birthplace Żelazowa Wola and the Chopin Foundation in Warsaw. At one point I said to Marek, “You know, I’ve been listening to these Chopin broadcasts, and it’s meant a great deal to me, and I wondered if it would be possible to meet those people who announce them.”

He said, “Why don’t you call up Radio Warsaw?” So I did and they said, “We’d love to meet you.” I was a thirty year-old graduate student. Nobody had ever heard of me. I was an unknown, never published a book. They welcomed me with open arms, this random American graduate student, and they interviewed me because they wanted to know why an American living in Regensburg would listen every night to Chopin. I told my little story, and I was introduced to the head of the foreign languages division of Radio Warsaw, and then to Maria Nosowska who was the woman who had created the program twenty-five years earlier. She’d done it five days a week for twenty-five years. And she was just completely devoted to Chopin. We spent four hours together listening to music. It was an amazing thing.

They told me my interview would be broadcast the day I got back. So I took the train back all the way back to Regensburg. I arrived in the afternoon. I went back to my little dingy room in this dingy dormitory. I had my little radio. I turned it on and put in a tape, and I taped myself fading in and out, talking about Chopin fading in and out. And I still have that.

This was again a desire for human contact. It had nothing to do with writing books or being famous or anything like that. I wanted to show these people how much their show, their program had meant to me, a lonely person in a foreign country to whom this had been a backbone of his stay for six months. Just like salsa was in Paris, Chopin was in Regensburg.

*This section was corrected for clarification.