For decades, the American Right has claimed children’s rights are anathema. They undermine the family, they threaten parents, they could destroy the United States and cause the downfall of Western Civilization. Probably the most succinct summary of rightwing sentiments about children’s rights comes from the late Chris Klicka, an attorney for the Home School Legal Defense Association who said in 2000 that, “If children have rights, they could refuse to be home-schooled, plus it takes away parents’ rights to physically discipline their children.” In other words, if children have rights, they could exercise autonomy and we would not be able to hit them.

But in the last few years, due in part to shifts in broader cultural norms, a new approach to children’s rights has emerged. While portions of the American Right have begun to embrace the language of children’s rights, they are using that language to promote their anti-child agenda. These efforts have been successful on many fronts, opening opportunities for the American Right to promote their ideology around the world and even in spaces like the United Nations. A pair of recent books from some familiar voices on the Right epitomize key elements of this new strategy.

They’re all groomers

Stolen Youth: How Radicals Are Erasing Innocence And Indoctrinating a Generation, written by Bethany Mandel and Karol Markowicz, is the perfect example of conservative efforts to make the public (and especially children) afraid of helping professionals. “Children can no longer trust their teachers, doctors, or the societal structures that claim to protect them,” Matt Walsh’s blurb declares. This theme—distrusting helpers—is, in fact, the main argument of Mandel and Markowicz’s book. Because helpers today have become “woke,” they argue, adults and children alike should avoid them.

Stolen Youth begins with Mandel and Markowicz claiming there is “danger lurking in every corner… [of] children’s lives, from their schoolroom, to their library, to their smartphone, to their television and beyond.” This danger, according to the authors, is ideological in nature: “the radical progressive Left—the woke—are trying to completely remake society and start a revolution.”

But there’s an obstacle in the Left’s way: they have fewer children than the Right, and children are key to revolutions. As a result, they argue, the Left tries to recruit children from the Right: “Their aim is ideological capture of a generation, but it’s not their kids they’re working to brainwash—it’s ours.” To accomplish this recruiting, the Left makes children “question every fundamental building block of society (‘What is a woman?’ ‘What is a man?’),” thereby causing them to “rebuild their entire sense of reality, concept of right and wrong, and vision for the future.”

While Stolen Youth is allegedly about advocating for children, the book primarily tells a story, not of the nefarious brainwashing of children by the Left, but of parents who alienate their own children. Take, for example, “Elissa’s story,” a case study of a non-binary sixth-grader who wants to be called Corey (instead of their birth name, Elissa) and their mother, Alison. Corey is experiencing significant struggles, including cutting and suicidal ideation. But when Corey, with the support of their mental-health team and public school, finally has the courage to tell Alison they’re non-binary and want to be called Corey, Alison refuses. She decides Corey has been “groomed” and forces them to transfer schools.

Tellingly, while the authors describe it as the child’s story, Corey is never quoted. We never, at any point, hear from Corey directly. The entire story is presented from Alison’s perspective, which is that Corey was preyed upon by mental health and school professionals. Furthermore, the authors give no indication that they even talked to Corey or made any other effort to verify Alison’s claims and descriptions. This practice—citing parents but not children—occurs throughout the book, meaning that nearly every story about a child is reported from the perspective of adults.

The absence of children’s voices is both telling and meaningful. It’s telling because it reveals that, while Mandel and Markowicz may speak eloquently about advocating for children, they’re more interested in advocating for parental authority and control over children. They speak disparagingly, for example, of gentle and democratic parenting, describing it as “inmates running the asylum” and arguing instead that parents should “wield control” over their children “mercilessly.”

And it’s meaningful because it communicates the authors’ belief that children should remain in a state of suspended innocence for as long as possible—a discredited notion popularized by philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the 18th century. In response to other philosophers who believed children are born either inherently selfish or as blank slates, Rousseau argued that children are born pure and innocent. Thus, a goal of Rousseau-inspired parenting is to prolong this pure and innocent state in order to protect children from any understanding of, or influence from, the adult world.

Mandel and Markowicz assert that children have both a “sexual innocence” and a “racial innocence.” But, they claim, people who are woke believe that “innocence is a sign of privilege and, therefore, something to be ashamed about—and something to be destroyed.” The authors cite James Lindsay—a rightwing provocateur who helped popularize the “groomer” conspiracy and believes that critical race theory will lead to the genocide of White people—to summarize the woke approach to children as, “Children can’t be innocent; they must be activists.” The opposite is implied to be the correct approach: in order to maintain children’s innocence, they must remain ignorant of injustices and be sheltered from efforts to address them.

This pursuit of childhood ignorance as innocence creates moral panic inflation. Whereas moral panics over childhood innocence have largely involved gender and sexuality, a moral panic can now be extended to any issue, including race, class, and even climate change. If you risk making a child feel bad or guilty about any subject or fact, you are now a groomer.

And this is the conclusion of Stolen Youth: helping professionals cannot be trusted because they are groomers. “Who would suspect a child’s therapist, teacher, pediatrician, or librarian of being part of widespread effort at indoctrination and manipulation?” But alas, under this wildly expansive definition, they are. The only solution, therefore, is greater parental control over children and a drastic reduction of exposure to helpers:

Parents need to assert their right to raise their own children [which] requires limiting, supervising, and monitoring the exposure children have to authority figures and messages that seek to usurp their parents’ proper role.

With helpers as threats, children’s worlds become much smaller. And studies demonstrate that isolation is the perfect breeding ground for child abuse. These suggestions are not best practices for child advocacy; they are red flags.

A global movement (of bigoted adults frightened by a rapidly changing world)

The other recent entry in this genre, Them Before Us: Why We Need a Global Children’s Rights Movement, is a deeply deceptive book. Written by evangelical Christians Katy Faust and Stacy Manning, the book presents itself as a secular defense of children’s rights and a call to listen to children’s voices on issues like marriage, divorce, and adoption. In reality, the book is an attempt to defend evangelical beliefs about family by highlighting the voices of bigoted adults.

In Them Before Us, Faust and Manning argue—without providing any evidence—that children require three things to “thrive outside the womb”: a mother, a father, and a stable, “Western-prescribed nuclear family.” They call these three needs the “critical socioemotional trinity.” On the basis of these needs, Faust and Manning argue that children have two rights: the right to life (defined as the right of a fetus to be born) and the right to family (defined as the right of a child to their biological parents).

In the two years since Faust and Manning published their book, they have expanded their list of children’s rights to include two more: the right of children to “reach adulthood with bodies that have not been chemically and surgically altered” (i.e., gender-affirming healthcare should be “banned for minors”); and the right of children to be ignorant about “topics related to sex and gender,” which means children should not receive sex education in school.

You will notice the four “children’s rights” identified by Faust and Manning are the current trending evangelical causes. Reproductive rights, diversity in families and parenting, gender-affirming healthcare, and sex education—all items that actual child advocates understand to be tools to protect and empower children—thus become the enemy. To defend this link between children’s rights and evangelical causes—to give it even the flimsiest social science veneer—Faust and Manning sprinkle stories from “children” throughout their book who share their worldview.

I put children in quotation marks because, while the authors share many personal narratives, the stories are deceptively presented. On the book’s back cover, we’re promised “kids’ perspectives,” yet in their introductory remarks the authors admit the narratives are “mostly authored by people in their forties, fifties, or sixties and sometimes older.” This means Them Before Us is less a global children’s rights movement and more a global movement of bigoted adults frightened by a rapidly changing world.

That the purpose of Them Before Us is ultimately to consolidate adult power is most apparent when Faust and Manning discuss parental rights. In their section titled “Children’s Rights Are The Flip Side of Parental Rights,” we read that “Parents have a right to their own children” and that “they have an inherent right to parent the child they bring into this world.” While many parents would agree with, or at least not find anything objectionable in, these assertions, this seemingly benign language has very specific, and very dangerous, roots in the American evangelicalism to which the authors belong. To evangelicals, parental rights mean more than adults having duties towards the children they bring into existence. Parental rights mean ownership. Children literally belong to, or are property of, their parents. As a result, children have few to no rights themselves (just four, according to Faust and Manning).

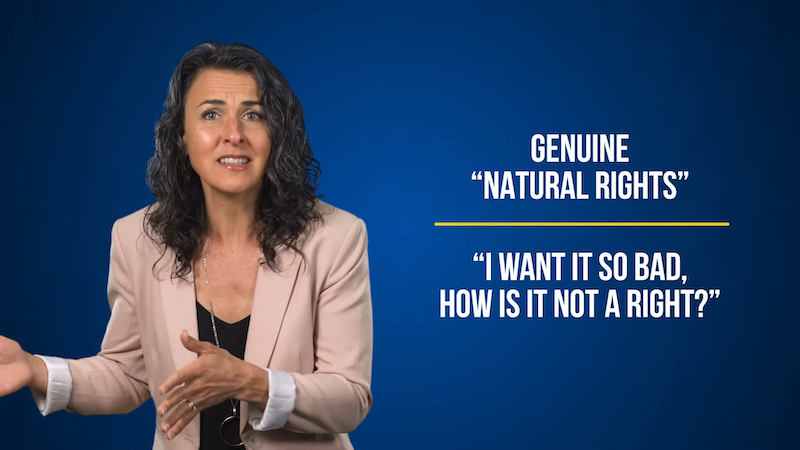

Katy Faust from a YouTube video “Do Children’s Rights Override Parental Rights?” produced by the Colson Center (launched by convicted Watergate felon Chuck Colson).

To better understand this position, we must look to the authors’ writing beyond the book. Elsewhere, Faust and Manning have repeatedly praised parental rights advocate and conservative Catholic philosopher Melissa Moschella as being representative of their view. Moschella is “the philosophical genius on parental and children’s rights,” Faust told evangelical apologist Sean McDowell on his Thinking Biblically podcast earlier this year. Moschella, an advisor to Faust and Manning’s non-profit advocacy organization, often speaks with Faust at conservative events, while Faust and Manning do not merely cite Moschella in their book, but also in articles and podcasts over and over and over again.

Moschella, the author of her own book called To Whom Do Children Belong?, believes children belong not to themselves, their community, or the government, but to their parents. In Moschella’s mind, the world is divided into a hierarchy of communities, each defined by authority: “Human beings are, in a sense,” she writes, “nested within various levels of community like the traditional Russian nesting dolls, communities that… exercise different degrees and types of authority over us.” And much like how American Christian Reconstructionists argue for sphere sovereignty, Moschella argues these various communities should mind their own business. Each community is “a kind of sphere of sovereignty,” she explains, and “parents have the authority to make controversial child-care decisions free from coercive state interference.” In other words, the government should not interfere with family matters.

“Except in cases where the authority of parents is clearly failing to fulfill its function—i.e., cases of abuse and neglect,” Moschella declares, the family should be considered “an authoritative community distinct and relatively independent from the larger political community with regard to its internal affairs.” This is the age-old conservative argument against any and every government attempt to oversee or regulate family matters—the same arguments used against compulsory education laws in the 1800s, against criminalizing child abuse and neglect in the early 1900s, and against federalizing our child protection system in the mid-1900s.

The problem is that our society has rejected these arguments. We rejected them because we decided that children are not mere property—of parents, communities, or governments. Children belong to themselves. While children require nurturance and guidance, requiring nurturance and guidance does not make a person someone else’s property. Adults with disabilities sometimes require these same things and we understand that does not mean the people who provide services to adults with disabilities own those people. So why would we think otherwise when it comes to children?

This inability to grant that children should be considered their own human beings is especially unfortunate because Faust and Manning are on to something important and real: “children are not items to be cut and pasted into any and every adult relationship.” Children are not objects to entertain or fulfill adults. They are their own beings with their own lives and rights.

Sadly, Faust and Manning only apply this truth to those adults and families they consider illegitimate and undeserving of rights (e.g., queer people, divorced families, etc.). They refrain from applying it universally, because to do so would undermine their non-negotiable belief in parental rights. So instead of a perceptive critique of the commercialization and commodification of children, we merely get repackaged evangelicalism.

The only winners are abusers

Stolen Youth and Them Before Us exist in an upside-down world, where everything is the opposite of reality: parents respecting a child’s right to be who they are becomes abusive and abusive behavior becomes both love for a child as well as a parental right. So respecting a child’s gender identity is seen as either grooming or child sexual abuse, whereas isolating a child from their LGBTQIA-affirming peers and mental health support team is accepted as both good parenting and a constitutionally-protected parenting decision. And you cannot object by appealing to actual experts because, according to Stolen Youth, all the experts are conspirators.

You have to pay close attention to how the authors of these two books constantly invert the truth, because the authors do offer significant lip service to the ideas of child advocacy and children’s rights. Them Before Us is even bold enough to cite the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, the most widely ratified treaty in human history. But Faust and Manning bury in the footnotes the fact that the United States is the only member of the United Nations that has not ratified the Convention, which is due to lobbying by evangelicals led by homeschool leader Michael Farris (the godfather of the parental rights movement).

Evangelicals incorrectly believe the Convention is a threat to parental rights, even though it explicitly affirms parental rights, declaring family is “the fundamental group of society” in its Preamble and that governments must “respect the responsibilities, rights and duties of parents” in Article 5. Despite this, evangelicals and other members of the American Right remain fearful of the Convention. The Parental Rights Organization, founded by Farris, is still, over 30 years in, issuing dire warnings about ratification.

This is the context in which Stolen Youth and Them Before Us set forth their upside-down interpretations of child advocacy and children’s rights. What they do with child advocacy and children’s rights is not simply incorrect, it is part of a long history on the American Right of perverting and weaponizing child protection. As I have written elsewhere, the problem with this theft of child advocacy and children’s rights is that it renders those fields powerless against actual child abuse. When child advocacy means isolating a child from friends and professionals, and children’s rights mean children should be kept ignorant about sex and gender, the only winners are abusers.