Read all previous installments here, or better yet, never miss another feature by signing up for the RD Daily Newsletter here. You’ll receive our features and blogs every day in your inbox.

There was a psychological logic, as well, to my transition from born-again Christian to Bowie votary. Rock fandom, taken to its obsessive extreme, is indistinguishable from the hallucinating, levitating ardor of an enraptured believer like, say, Saint Teresa of Ávila. The etymological origins of the word are helpful: “fan” is short, of course, for “fanatic,” from the Latin fanaticus, “mad, enthusiastic, inspired by a god,” deriving from fanum (“temple”) and related to festus (“feast”).1

Some sources smell a whiff of orgiastic rites still clinging to the word, which would explain the tale told by a fan named Julie, in Fred and Judy Vermorel’s 1985 study of fan culture, Starlust—a bizarre (and, be it said, thoroughly unsubstantiated) account of a spontaneous outbreak of Dionysian frenzy at Ziggy’s 1973 farewell concert, in which:

a lot of men were throwing off their underwear and showing their cocks all over the place…I thought it was so extraordinary because nobody had any inhibitions. I remember that around me nobody gave a shit really about doing these things because it was rumored that maybe this was the last time Bowie would perform. Maybe this was the last time Ziggy would be here. And everyone’s got to get in on this because otherwise you’re just a square. […] Then I suddenly realized that all the things I’d been doing were perfectly O.K. Because here were people doing it with each other and sharing it. How wonderful, you know. So get off on that. And I thought I’d never seen so many cocks in my life.2

Holy communion in The Church of Man.

By the way, I’m not using the term “Dionysian” lightly. In The Great Transformation: The Beginning of Our Religious Traditions, the religious historian Karen Armstrong describes the carnival atmosphere that prevailed at celebrations of the Dionysian mystery cult: “Everybody drank wine, and there was music and dancing” and “sometimes, the whole group fell into a trance, a heightened state of consciousness, which spread from one celebrant to another. […] They called this experience of divine possession entheos: ‘within is a God.’”3; Oh, and “men wore women’s clothes, like the young Dionysus when he was hiding from Hera.”(Emphasis mine.)

A devout fan strives in every way to imitate his idol—to become him, in fact, in the same way that the Dionysian celebrants whipped themselves into a delirious state of divine possession; in the same way that the 16th-century Catholic mystic Saint John of the Cross strove, through the Imitation of Christ, to attain an ecstatic oneness with God; in the same way that charismatics fervently desire the “indwelling” or “infilling” of the Holy Spirit, so that they may live “spirit-filled” lives, guided by God’s will (entheos); in the same way, perversely, that the deranged Beatles fan Mark David Chapman was convinced that killing John Lennon would transform him into a household deity like his idol, a “guardian angel” maybe, or even a “quasi-savior.”4

A fan is a consumer whose all-consuming idolatry is just the well-behaved face of a sublimated desire to actually consume the love object. What more intimate and irrevocable way to have that faraway figure on the Jumbotron screen, the unattainable figment of a million fans’ fever dreams, all to oneself? The gonzo rock critic Lester Bangs winks at the inherent depravity of “psychofandom” in his gore-nographic fantasy of gobbling up a “giant rotten glob” of Elvis’s carcass in order to ingest the King’s magical powers: “I don’t need to go get The Golden Bough just to prove to everybody else what I already know because it’s simple horse sense, which is if I eat a little bit of Elvis (the host, as it were, or is that mixing mythologic metaphors?), then I take on certain qualities possessed by Elvis when he was alive…”5

As Bangs’s invocation of Frazier’s Golden Bough and the sacrament of holy communion suggests, fans’ appropriation of their idols’ hairstyles, fashion statements, signature poses, and, in some extreme cases, distinguishing features is only the latest stop on the elevator ride up from the basement of the religious unconscious—the postmodern return of one of the most primitive manifestations of the fan mind, namely, ritual cannibalism, in which participants absorb an enemy’s magical powers by eating his flesh.

Following Freud’s analysis, in Totem and Taboo, of the Christian Eucharist as a revival of that ancient totemic practice, unbelievers have gotten endless mileage out of the obvious correspondences between ritualized anthropophagy and the rite of communion, arguing that the Last Supper is just a sublimated blood feast. (The Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, which holds that the consecrated wafer metamorphoses miraculously into Christ’s flesh, has been god’s gift to irreverent wags.)6

Yet little, if anything, has been written about the conceptual hyperlinks between Christ’s solemn promise to his disciples, “whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood remains in me, and I in him” (John 6:53-56), and the quintessential fan practice of incorporating iconic aspects of the star’s appearance and attitude into his psyche—what Freud would call introjection—in order to be born again, into a more liberatory identity.

Fans remake themselves in their idol’s image by metaphorically tearing him to pieces, like Ziggy in “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide”—obsessively collecting and fetishizing photos, videos, concert memories, celebrity sightings, memorabilia, and other hallowed fragments of the divinity, from which they assemble new, recombinant selves. In an unguarded moment, Bowie traced his own metamorphosis from devotee to deity:

I took a look at my thoughts, my appearance, my expressions, my mannerisms and idiosyncrasies and didn’t like them. So I stripped myself down, chucked things out and replaced them with a completely new personality. When I saw a quality in someone that I liked, I took it. I still do that. It’s just like a car, replacing parts.7

This is what the music critic Simon Reynolds means when he talks about the “circularity” of rock fandom, “where fans grow up to be idols, having learned the art of posing from their idols.”8

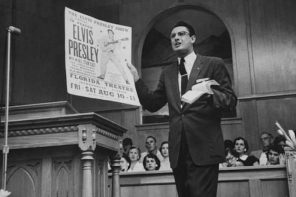

Hence the importance, in fan culture as in Roman Catholicism, of miraculous relics: objects the star has touched, like the Concert Used Handkerchiefs—Lot 106 in the auction catalogue for the Gary Pepper Collection of Elvis Memorabilia, “owned by audience members who gave them to Elvis Presley to wipe his face during a concert, after which they were returned. Unwashed.”—or, better yet, consecrated remnants of the star himself, like Lot 66,9 the Large Quantity of Elvis Presley’s Hair, sure to be “treasured by fans who wish to own a piece of the king himself.”

Talismanic objects such as ticket stubs and tour T-shirts are more common; most common of all are venerated images displayed on bedroom walls: on the Bowie fansite Ziggy Stardust Companion, an ardent fan named Madeline proudly displays a blurry snapshot of her “Ziggy wall.”10 (image, upper right).

Wall-mounted photo collages are devotional aids—focal points for inner dialogues with the deity, daydreams, wet dreams, wish-fulfillment fantasies involving fan and star or fan as star. Intimately situated in a teenager’s Fortress of Solitude (her bedroom), they’re domestic shrines, depicting the tutelary god at his most iconic, styled and posed and lit (if clothes make the man, lighting makes the god in celebrity portraiture and Christian iconography alike), then retouched into an unattainably idealized version of Himself—a Photoshop apotheosis.

Icons have played a key role in the contemplative lives of Christians for centuries, putting an approachably human face on the deity while concentrating the mind on otherworldly things. Saint Teresa had her first mystical catharsis when she entered a chapel and stumbled on an image someone had left behind, a picture of the wounded Christ that stirred her soul as no picture ever had, literally bowling her over, leaving her on the floor in “a great flood of tears,” overmastered by the feeling that “He was within me, or that I was totally engulfed in Him.”11

In American Jesus: How the Son of God Became a National Icon, the historian of religion Stephen Prothero traces the history of chromos, wallet-sized prints, posters, and other mass-produced images as zeitgeist weathervanes, spun this way and that by changing attitudes toward Jesus. Shaped by the cultural politics of a given historical moment (think of the longhaired, drop-out Jesus of the Jesus Freaks or the fan-mobbed, fame-sick messiah of Superstar), such images also shaped popular conceptions of the Son of God—one of the tight feedback loops typical of a highly networked, mass-media age. “Advances in printmaking made lithographs affordable in the first half of the century and halftone engravings inexpensive in the last,” he writes. “As images of Jesus proliferated in illustrated books and prints suitable for display in the home, Americans increasingly approached God through images as well as texts, and those images reinforced their devotion.”12

In the dream life of American culture, mass-marketed depictions of Jesus, from Warner Sallman’s pensive, doe-eyed Head of Christ (1941), distributed by the millions to servicemen during World War II, to the Fabio-haired prizefighter messiah of Stephen S. Sawyer’s Undefeated (1999), have left an indelible stamp on the inner lives of believers. “When devout viewers see what they imagine to be the actual appearance of the divinity that cares for them,” the art historian David Morgan contends, the picture in question “becomes an icon”—an image with a life of its own, charged with the divine presence.13

“When I look at [Sallman’s Head of Christi] in prayer, and when I am the most in need,” says a believer quoted by Prothero, “I see not only a painted portrait, but the face of the real, the living Christ.”14

Spoken like a fervent Bowie fan, one of those worshippers who are “most in need,” desperate to be healed by the Master’s touch as he passes by, frantic to kiss his hand—or to “crush his sweet hands” if he turns out to be a false idol, “making love with his ego” (“Ziggy Stardust”) instead of us, his frenzied votaries, Maenads of a secular mystery cult.

In our epic saga’s last (!) installment, the author looks back on his teenage-fanboy crushes on Jesus, then Ziggy, thirty-six years after the fact, and can’t help wondering: What was that about!?

Endnotes:

1Fanatic. Dictionary.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper, Historian. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/fanatic.

2Quoted in Fred and Judy Vermorel, Starlust (London: Comet Books, 1985), pps. 182-183, archived on the “Retirement Gig” page of The Ziggy Stardust Companion, http://www.5years.com/Retire.htm.

3Karen Armstrong, The Great Transformation: The Beginning of Our Religious Traditions (New York: Anchor Books, 2007), pps. 221-2.

4See “Motivation and Mental Health” section of the Wikipedia entry on Mark David Chapman, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_David_Chapman#Motivation_and_mental_health.

5Lester Bangs, “Notes for Review of Peter Guralnick’s Lost Highway; 1980,” quoted in Greil Marcus, Dead Elvis: A Chronicle of a Cultural Obsession (Boston, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), p. 172.

6Catholics would argue that, while the essence of the host is transformed, those aspects of the sacrament that are apprehensible to the senses (“the accidents”) remain unchanged, thus ensuring that celebrants are not, in fact, cannibalizing the Divine—-an awkward bit of theological footwork that, to my mind, is nothing more than an attempt to dodge the bullet of atheist mockery, not to mention skeptical inquiry, however unconvincingly.

7Quoted in George Tremlett, David Bowie: Living on the Brink (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1997), pps. 20-1.

8Marc Spitz, Bowie: A Biography (New York, NY: Crown, 2009), p. 316.

9Auction catalogue for The Gary Pepper Collection of Elvis Presley Memorabilia, http://issuu.com/lesliehindman/docs/sale120_elvis.

10 See http://www.5years.com/madx.htm.

11Cathleen Medwick, Teresa of Avila: The Progress of a Soul (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999), pps. 38-39.

12Stephen Prothero, American Jesus, ibid., p. 144.

13Quoted in Prothero, ibid., p. 118.

14 Quoted in Prothero, ibid.