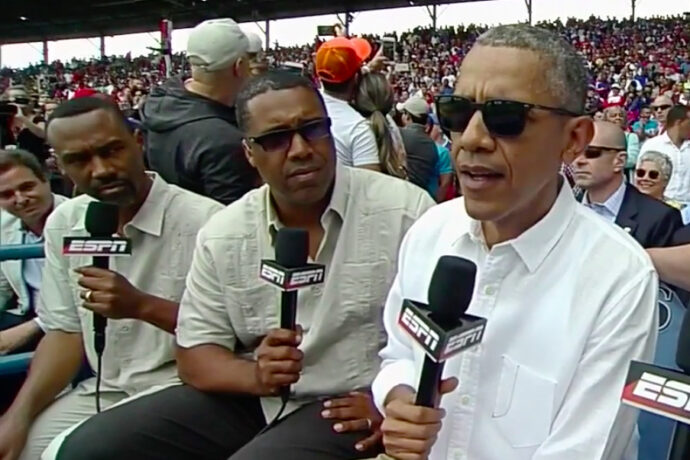

On a historic trip to Cuba this week, and in the wake of a terrorist attack in Brussels, President Obama sat in a Havana stadium extolling the sacred power of baseball to a trio of ESPN commentators:

I did not play a lot of baseball as a kid; I was more of a basketball player, but there is something about baseball that is so fundamentally woven into our culture. And in some ways, at a time in our lives where everything is a mile a minute and kids are on their phone all the time and there’s just this constant stream of information, there is nothing like going to a ball park and just everything slowing down a little bit, and the rhythm of the game gives you a sense of appreciation about all the blessings we have. It’s still a family game in a way that is really hard to match.

And to those who found his presence at an exhibition game distasteful or disrespectful in the face of the world’s grief, he responded, “The whole premise of terrorism is to try to disrupt people’s ordinary lives.” One of his proudest moments as president, he explained, was watching a defiant David Ortiz, one of the many Major League Baseball players from the Dominican Republic, respond to the Boston Marathon bombing with a resounding and defiant message of unified goodwill against pockets of hate, “This is our f—ing city!”

Hence, for much of Tuesday’s monumental matchup between the Cuban national team and the Tampa Bay Rays, Obama was an enthusiastic fan, exchanging pleasant smiles with his neighbor, President Raul Castro. If baseball can re-enchant our frenetic lives with a temporal frame that encourages deep reflection on the “blessings” of the American experience, what happens when the sport symbolically mediates an encounter with a country that supposedly fosters a very different way of life? Chris Archer, a 28-year-old pitcher for the Tampa Bay Rays, and most voluble spokesman for this round of baseball diplomacy, was optimistic:

Hopefully, the Rays are showing the people of Cuba, the government of Cuba, what can be, for lack of a better term, afforded to them if they do open their doors and start being a little more open-minded about their policies.

The idea of baseball as a political tool of American foreign policy is not a new one.

In 1913, James Sullivan, dispatch minister for the Dominican Republic, suggested to Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan that baseball could exorcise political demons in that Latin American nation, while also diffusing anti-U.S. sentiment.

The manifestation of resentment toward Americans, this is merely on the surface, I believe, and will disappear if the American Government makes any attempt to win the good will of Dominicans . . . I deem it worthy of the Department’s notice that the American national game of baseball is being played and supported with great enthusiasm. The remarkable effect of this outlet for the animal spirits of the young men is that they are leaving the plazas where they were in the habit of congregating and talking revolution and are resorting to the ball fields . . . [Baseball] satisfies a craving in the nature of people for exciting conflict and is a real substitute for the contest on the hillsides with the rifles.

But if baseball quelled some early revolutionary ferment in the Dominican Republic, it proved an easy, if ironic, ally of Fidel Castro and his revolutionary cohorts in Cuba. In the United States, football has arguably supplanted baseball as the national pastime. Cuban baseball has had no such rivals.

It is not surprising then that a game in the hallowed Estadio Latinoamericano would produce what at least one U.S. sports journalist perceived as religious moods. JP Morosi of Fox Sports described the sacred aura of the pregame pomp:

A Cuban women’s choir, all in white dresses, singing two national anthems—Cuba’s first, with the gentle accompaniment of 50,000, as if the faithful at church. The devotion was audible, as tickets were distributed to friends of the Cuban government and not through a public sale.

Here the religious nature of the Cuban sporting event is acknowledged only to be dismissed as inauthentic. The patriotic, quasi-religious crooning is suspicious because of its apparent production by the Cuban government, which distributed tickets to friends. Morosi recognizes religious moods can be manufactured for diverse political ends and are thus not to be entirely trusted. But he has great faith in what he believes this particular sporting contest represents—freedom and the American Dream.

And that is why, from behind the wheel of a 1950s Chevy, one taxi driver told me something I’d heard other Cubans intimate but never say explicitly: “I love America.”

Had he been there before? No, he said. “But if Obama can come here,” he told me, “then maybe I can go there.” He didn’t explain how he could love a country he’d never seen. We both knew why: the freedoms I enjoy, which he does not have.

This is an astounding recollection, both for its frank admission and potentially worrisome projections. Morosi admits he didn’t need to receive (or ask for?) any deeper explanation for the driver’s declaration of cross-country love because he already knew the answer.

In this respect Morosi replicates a longstanding pattern in the North American framing of Latin America in general and Cuba in particular: the idea that their realities are transparent and go without saying because, while the United States is a place of complexity and opportunity, Cuba is one of simplicity and degradation. According to this model, the American Dream is so appropriately irresistible and ubiquitous that it animates the deepest longings of taxi drivers in Cuba, who don’t need to offer us elaborations about such desires because they had us at “I love America.”

To appreciate the ways religion and baseball have often been imbricated in U.S. representations of Cuba, consider the film Major League. The comedy was released in 1998 but is a bona fide cult classic years later, a status bolstered by Netflix and its ilk. One of the film’s most popular characters is a Cuban exile named Pedro Cerrano, who crushes fastballs but is sent into histrionic tailspins by curveballs. He thus pleads with a rum-drinking, cigar-smoking deity named Jobu to help him with his hitting. Jobu is the most prominent figure in Cerrano’s religion, a system of symbols and ritual devotions which the film ominously introduces as “Voodoo.” Viewers also learn that Cerrano left Cuba for the United States because of religious persecution.

But Cerrano’s baseball salvation, hitting a triumphant home run in the final game, comes only when his religious devotion ends, as he offers an off-color declaration of American individualism, “F— you, Jobu! I do it myself.”

While the idea of a religious exile losing his foreign religion and converting to the American Dream provides laughs in Major League, the history of human rights abuses in the sacred spaces of Cuba creates real-life anguish for Cuban-Americans like ESPN journalist Dan Le Batard, who writes,

My grandmother put my mother on a plane believing they might see each other again in three months. It took 12 years. Grandma put her on a plane because she couldn’t stomach the idea of both of her children being in jail at once—her son for his politics, her daughter for trying to go to church to honor the dead. Days after she fled, three militia members with machine guns broke into the house at 3 a.m. looking for my mother.

That tragic legacy had Le Batard feeling conflicted about Obama’s visit, and especially about the president exchanging pleasantries during a baseball game with representatives of a regime he charges with so much of his family’s sorrow.

The embargo didn’t work. I get it. America does a lot of business with dictators. I get it. My parents aren’t close-minded, heartless or blinded by unreasonable rage. They’d be all for normalized relations with Cuba if it meant helping, you know, the citizens of Cuba. And maybe this will. Or maybe it won’t.

When Le Batard watched the video of a Cuban dissident momentarily seize ESPN’s broadcasting platform in Havana to yell against the human-rights abuses of the Castro regime, before being swiftly and forcefully apprehended and pushed into a car, Le Batard felt no ambiguity. Nor could he muster words. He choked on tears and motioned for a commercial break to his radio broadcast.

Sporting events, like civil religion, can provide pluralistic spaces of resiliency in the face of terror. Many claim baseball did that after 9/11. Obama is a believer in that legacy. But the power of sports to produce heightened emotional states of unity, which scholars call “collective effervescence,” can also give it a shared power with religion to occlude injustice in this world, to bury it in cheap, playful sentiment. Sports, like religion, and like the American Dream, will thus continue to be contested symbolic terrain, where the stakes can prove much more complicated than zero-sum games, and the vexed emotional legacies much longer-lasting than nine innings.