Today’s public discussion of Christian nationalism is led in part by a group of conservative anti-Trump evangelicals, many of whom write for centrist or center-left publications. Yet, for all their eloquence, they persistently fail to acknowledge that previous generations of evangelicals held the very same views these contemporary writers rightly criticize in today’s evangelicalism. One hopes that this collection of writers—notably, David French, Peter Wehner, Tim Alberta, Russell Moore, and David Brooks—succeed in weakening the minority authoritarianism at the heart of Christian nationalism and of Trump’s popularity. But from their writing, one would conclude that people and groups with a novel sensibility had hijacked what had been, until their arrival, a wholesome, democracy-affirming, and love-centered evangelicalism. The actual history of the United States invites a deeper critique of evangelicalism.

Long before the era of Donald Trump, evangelical Protestantism as a lived faith in the United States carried strong nationalistic, anti-statist, xenophobic, White supremacist, misogynist, and homophobic elements. These elements were bound up with a Manichean sense that Christians were in an existential battle with Christ’s enemies, and combined further with a strong sense of entitlement to the land. Not all evangelicals endorsed those elements, but lots and lots did. In the late 1940s and early 1950s the National Association of Evangelicals asked that, following the model of the Confederate Constitution, the US Constitution be amended to include God and Jesus. When Congress invited comments on the proposal, 41 Jewish organizations and some non-evangelical Protestant groups opposed it and it failed. In other words, Christian nationalism is not new.

We now have a formidable body of scholarship that establishes the depth and extent of these features of the American evangelical tradition, confirming and expanding on Richard Hofstadter’s legendary analysis in his 1964 book, Anti-intellectualism in American Life. This new body of scholarship is the work of a remarkable generation of young historians who have yet to receive the credit they’re due, so I name some of them here: Darren Dochuk, Matthew Sutton, Anthea Butler, Timothy Gloege, Jesse Curtis, Lerone Martin, J. Russell Hawkins, Stephen Young, Daniel Hummel, Daniel Silliman, and—the only one in this cohort to gain wide media recognition—Kristin Kobes Du Mez, author of the justly famous and marvelously titled, Jesus and John Wayne. Sadly, while the majority of these scholars have written for Religion Dispatches, the conclusions of these bold and creative scholars have been largely ignored in the discussion of religion and politics found in the pages of The Atlantic, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and other media of comparable reach and influence.

This earlier history is easy to ignore since the problematic features of evangelical Protestantism were much less consequential until the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Two portentous, virtually simultaneous developments changed that.

First, evangelical Protestantism was catapulted from the margins of public life into its center when it was adopted as a major constituency by the Republican Party. Second, the decline in membership and civic leadership of the old mainline denominations—the Presbyterians, Methodists, Episcopalians, and so forth—hollowed out the edifice of American Christianity, a space quickly occupied by evangelical Protestants and their most conservative Catholic allies, heavily bankrolled by wealthy, anti-regulation capitalists. This second development meant that the local franchise of the global Christian project, long held by the mainline, ecumenical Protestants, fell into the hands of evangelicals—and this happened exactly at a time when, as a crucial voting base for the Republican Party, evangelical power was on the rise.

One of these developments—the cultivation of evangelicals by Republicans—has been extensively discussed. The second—the popular assumption by the media that Christianity is defined by evangelical beliefs and positions—isn’t widely understood, so I’ll focus on that development and explain how the two came together.

Central to this story of how our increasingly secular society came, paradoxically, to be saddled with an increasingly religious politics is the historic rivalry between ecumenical and evangelical Protestants—a rivalry that sharpened and deepened between the 1920s and the 1960s. The leadership of the ecumenical denominations that eventually came to be called “mainline,” carried out during those decades a campaign for a more critical, cosmopolitan Protestantism.

These Methodists, Lutherans, Congregationalists and so on, took a firm stand against Jim Crow at home and against colonialism abroad. They welcomed interpretations of scripture that were compatible with modern standards of epistemic plausibility. They sponsored up-to-date translations of the Bible. They supported Alfred Kinsey’s sex research and encouraged the use of contraceptives. They were massively committed to the new United Nations and, through their major role at the San Francisco Conference of 1945, were largely responsible for its Human Rights Commission and its Trusteeship Council. They stood down efforts by European delegates to place in the UN Charter a guarantee of the right to proselytize, for fear that the world’s Hindus, Muslims, and Buddhists would find the UN too Christian. Those in the church pews often failed to follow these initiatives, but church leaders cut a conspicuous swath through American public life during the mid-century decades—a swath that was decidedly pluralist, democratic, and internationalist.

These cosmopolitan-aspiring steps of ecumenical leaders annoyed evangelicals, who blasted the UN for not being avowedly Christian and scorned the other elements of the ecumenical campaign as substituting politics for religion. They stood by the King James Version of the Bible, and accused the liberals of changing a gospel that the seventeenth-century English scholars got exactly right. The evangelicals developed a set of institutions explicitly designed to counter the mainliners, creating the National Association of Evangelicals, Fuller Theological Seminary, Christianity Today, and a huge network of radio and television stations and programs.

Evangelicals redoubled their commitment to convert the “heathens” of the Global South exactly when ecumenicals pulled back from the goal of conversion, which they increasingly considered to be too imperialistic. This difference in missionary outlook strikingly illustrated the persistent evangelical belief that the world was theirs to exploit on behalf of their Lord, and the growing ecumenical belief that the world was to be shared respectfully with people of other faiths and all races. In fact, evangelicalism as it was solidified in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, took specific shape in direct response to the critical initiatives of ecumenicals. It is not an exaggeration to say that evangelicalism developed as a giant protest movement against the liberalization of American Protestantism.

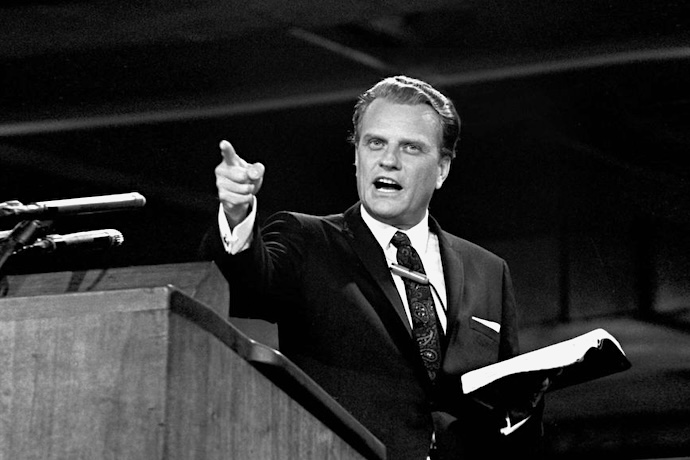

Evangelical churches flourished as safe harbors for White Americans who wanted to be counted as Christian without engaging the challenges of an ethnoracially diverse society and a scientifically-informed culture that the mainline leadership embraced. Protestants had a choice. Those who chose evangelical churches rejected an easily available alternative led by people who were nearly all just as White as Billy Graham but who read the Bible very differently. Biblical interpretation actually matters.

While all this was happening, the mainline denominations were most definitely still in control of American Christianity. Catholics were smaller in numbers and had a much weaker class position. The mainline churches had growing memberships, media connections, and they dominated all three branches of the federal government. In 1963, mainliners were proud to publish Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from the Birmingham Jail” in their house organ, The Christian Century, while FBI strongman J. Edgar Hoover was the darling of evangelical leaders and Billy Graham declared, in response to King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, that Black and White children would walk hand in hand in Alabama “Only when Christ comes again.” Ecumenicals treated the evangelicals like poor country cousins, but for all their complacency and sense of superiority, they constituted a vital, countervailing force against evangelical influence in American public life.

Then, after the 1960s, the ecumenical denominations began their precipitous decline in membership. Although some churchgoers switched to evangelical churches, most of the decline had three other causes. First, the birth rate declined rapidly as the ecumenicals promoted contraception and encouraged the entry of women into the workforce. Evangelical parents had scads of children, more even than Catholic parents during the baby boom and the decades following. Second, and yet more important, millions of young people left their parents’s church, having become involved in secular communities promoted by the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, just at a time when evangelical families were more successful at keeping their young (often by turning to private Christian schools to avoid racial integration).

And finally, the mainline churches were no longer able to successfully recruit members from the evangelical churches, as they’d long done, because evangelicals had become less marginal, thanks to effective institution-building and Republican Party support. You could be counted as respectable without moving up from the Nazarenes or the Assembly of God to the Presbyterians or the Methodists, as was previously the norm. You no longer had to be mainline to be mainstream. Ronald Reagan’s embrace of evangelicals in 1980 consolidated this transition.

The free-falling mainliners largely withdrew from their long-standing role in public affairs. Hence, there were fewer critiques of the sort John C. Bennett made in his important 1958 book, Christians and the State, when he insisted that Americans are not “a Christian people” and should renounce the habit of describing themselves in that way. T. S. Eliot’s Idea of a Christian Society, then widely admired in many religious circles, could not apply to a pluralistic democracy like the United States with a substantial Jewish population.

Reinhold Niebuhr, Bennett’s more famous Union Theological Seminary colleague, identified the popular evangelist Billy Graham as an example of Niebuhr’s favorite spiritual target: American innocence. Niebuhr complained that Graham spoke to the most immature of religious emotions, and was hopelessly provincial. Graham displayed no knowledge of “the continuing possibilities of good and evil in every advance of civilization, every discipline of culture, and every religious convention.”

This traditional critique of evangelicalism by mainline Protestants diminished in frequency and intensity exactly during the post-1960s decades when evangelical ideas became more prominent in American politics. Secular voices rarely took up the cause of criticizing evangelical religious ideas as such. The secular critique focused on the racism, misogyny, and homophobia of the evangelicals, and on their flawed reading of the Constitution, but rarely addressed the alleged scriptural warrant for these features of evangelicalism. After conservative Catholic Amy Coney Barrett was confirmed for the Supreme Court in 2020 with massive support from evangelicals, Linda Greenhouse complained in The New York Review of Books that secularists “do not know how to talk back” to evangelicals, and don’t even know “how to frame the questions.”

Candidates for the federal bench or for elected office couldn’t be questioned about their religion—even if being “a person of faith” was said to be a point in their favor—without the questioner being accused of bias against religion (although ‘religion’ in this context is frequently a euphemism for ‘Christianity’). Thus we end up with any and all specific religious ideas being largely excluded from public debate even as the influence of those ideas has dramatically increased, and the percentage of Americans who profess Christianity has declined.

An ironic consequence of the secularization process was thus the loss to the nation of a once-vigorous voice that defended a less nationalistic, less racist, less misogynist, less homophobic model of Christianity—one that fit quite well with majoritarian democracy. The evangelical seizure of the American franchise of the most successful cultural project in the history of the North Atlantic West—Christianity!—and the consequent weakening of the religious forces that traditionally contained evangelicalism, have done much to enable the minority authoritarianism that now threatens American democracy.

However much today’s anti-Trump evangelicals accomplish, their writings advance with increasing frequency a liberal-pluralist version of the faith that was long espoused by the hated ecumenicals. This dynamic of appropriation and effacement suggests that the old Protestant Establishment, for all its limitations, got a few things right. When secularists and other non-Christians hear of conflicts between rival groups of Christians they may say to themselves, “I don’t have a dog in that fight.” But they do. We all do.