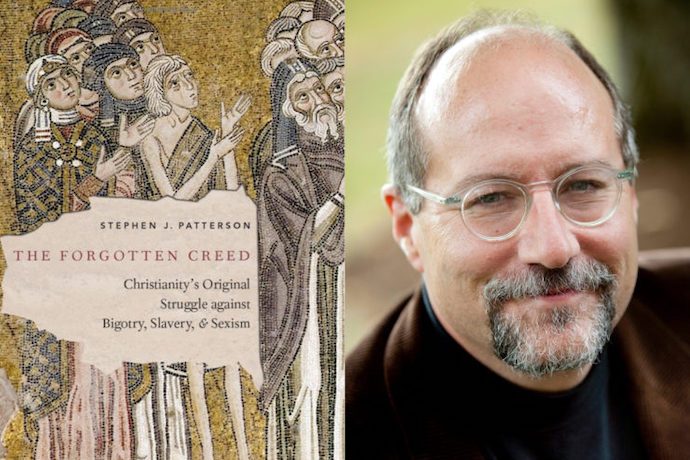

The following is a lightly edited excerpt from The Forgotten Creed: Christianity’s Original Struggle against Bigotry, Slavery, and Sexism by Stephen J. Patterson. Copyright © 2018 by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

On a warm, June Sunday in St. Louis I wandered with an old friend through the church where, earlier that morning, my children had been baptized. We came to the baptismal font, around which our family had gathered for the ceremony during the regular Sunday service. It was about four feet high, just low enough for my daughter to reach up and fiddle her fingers in the water and watch the droplets dribble back into its shallow pool. My friend, who had grown up in a secular upper-class home in Tito’s Yugoslavia, had little knowledge of fonts and baptism and the goings-on that morning. So he asked, what does it mean, baptism?

The question gave me pause. When you baptize a baby, it is a kind of naming ceremony, like those found in many societies. When you are baptized, like I was, on the eve of puberty, it is a coming-of-age ceremony, a rite de passage—again, a common practice across cultures. Sometimes, though rarely, an adult is baptized. Then it signals a religious conversion, the culmination of a profound personal transformation. I rambled. “But what do you think it means?” he asked. It was a fair question. I had just seen my own children baptized.

“It means,” I said, “you’re a child of God.”

“So you’re saved?” No. That’s not what I meant. That is what most people assume it means. That is what most people think the Christian religion is all about: salvation. But that is not really it. Earlier that morning the minister had used words from an ancient, nearly forgotten credo once associated with baptism. “You are children of God,” she said. “There is no Jew or Greek, no slave or free, no male and female.” The words were from a letter of Paul the Apostle, who had taken them, in turn, from an ancient baptismal creed he had come to know through the Jesus movement. That is what it’s about—being a child of God. Ethnicity (no Jew or Greek), class (no slave or free), and gender (no male and female) count neither for you nor against you. We are all children of God. He was skeptical. An early Christian creed about race, class, and gender? Unbelievable.

Why not be skeptical? What has Christianity ever had to say about race, class, and gender? I suspect that most people would think nothing good. Sunday morning is still the most segregated hour in American life. From the time African slaves first began to convert to the religion of their masters, whites prohibited blacks from worshipping with them—still true in most American churches until after the civil rights era.

Then, in the 1960s, white churches began to “open their doors” to African Americans and—surprise—most blacks said “thanks, but no thanks.” This wasn’t major league baseball, after all. Most African Americans preferred to worship in the churches their ancestors had built of necessity—theirs, now, by choice—rather than join churches that had shunned them for more than a century. The story of race and religion in America is pocked with indignities large and small. So, while police departments, public schools, restaurants, the United States military, and baseball have all become racially integrated, America’s churches have not. It may be that the church is the last truly segregated public space in America.

How about class? Does Christianity have anything helpful to say about class? Perhaps. You might hear “blessed are the poor” on any given Sunday, but more likely you will hear “blessed are the poor in spirit.” The words of Jesus are assumed to be about your spiritual life, not your finances—unless, of course, you attend one of the larger, far more successful churches where the “prosperity gospel” is preached, where the word is always about your finances. If you believe, keep the right company, straighten out your life, and tithe, you will prosper. The millionaire preaching these words to you is a witness to his own truth. The faithful definitely will prosper. And what of those who do not? Well, anyone can read those tealeaves. In today’s fastest-growing churches, the gospel is all about class.

And gender? Simply put, the church is the last, greatest bastion of gender bias in American society. The Catholic Church does not ordain women as priests and probably never will. Neither do the Orthodox churches. The largest Protestant denominations do not ordain women as ministers, nor do most of the historically black churches. Only the small denominations once known as the “mainline” churches ordain women—and these are the churches that are in decline. My own United Church of Christ, the oldest church in the United States, which ordained the first woman minister in the mid-nineteenth century, now has fewer than a million members. Today the Mormons outnumber the church of the Pilgrims seven to one—and the Mormons are not ordaining any women. The church is the last institution in America where it is still legal to discriminate on the basis of gender.

So, an ancient Christian credo declaring solidarity across ethnic lines, class division, and gender difference sounded a little unbelievable to someone who had come to see the Christian church as more a symbol of social ills than of starry-eyed utopian dreams. And that these words could have come from the Apostle Paul—to anyone with a passing familiarity with Christianity—would have seemed more incredible still. Most people today assume that Paul is the father of Christian anti-Semitism, was profoundly misogynistic, and was authoritarian when it came to slavery. Let wives be submissive and slaves be obedient, he taught. Or so they think. And why not? Clear statements to that effect appear in the New Testament letters claiming the great apostle’s authorship—Colossians, Ephesians, 1 Timothy, and Titus. But every beginning student of the Bible learns that these letters are pseudonymous, forgeries. Paul did not write them. On the other hand, Paul himself did indeed write the Epistle to the Galatians, including the remarkable words of Galatians 3: 26–28:

For you are all children of God through faith in Christ Jesus; for as many of you who have been baptized have put on Christ: there is no Jew or Greek;

there is no slave or free; there is no male and female;

for you are all one in Christ Jesus.

The debate about the meaning and significance of this passage began already in the early twentieth century. In 1909, the German Catholic scholar Johannes Belser noticed it and its remarkable claim and argued that Paul could not have meant anything social or political by it.1 It simply meant that everyone is equal in the sight of the Lord. But the Protestant Liberal Heinrich Weinel, who helped to found something called the Freie Volkskirche (the Free People’s Church), a hotbed of theological liberalism and social democratic reform in early-twentieth-century Germany, saw it differently. He argued that Galatians 3:28 was at the heart of Paul’s radical social vision—even if his own nerves would not quite tolerate the fullness of that vision in real time.2

Today, most scholars do not deny the radical social and political implications of the saying, but they also do not assign the verse directly to Paul. To be sure, Paul wrote it into his Galatian letter, but for reasons I detail in The Forgotten Creed, most students of Paul believe that he was drawing upon an ancient creedal statement originally associated with baptism. Paul knew it and quoted it, but he did not compose it. That honor belongs to some early Christian wordsmith now long forgotten.

The credo itself has also been mostly forgotten. The current, state-of-the-art scholarly treatment of the earliest Christian statements of faith scarcely mentions it.3 A recent nine-hundred-page study of baptism in the New Testament refers to it only in passing.4 Again, why not? In the long history of Christian theology, spanning centuries and continents, this creed has played virtually no role. How could it? The church became a citadel of patriarchy and enforced this regime wherever it spread. It also endorsed and encouraged the taking of slaves from the peoples it colonized. And within a hundred years of its writing, “no Jew or Greek” became simply “no Jews,” as the church first separated from, then rebelled against its Jewish patrimony, eventually attempting patricide.

But thoughtful and sensitive scholars still studied the creed. I recall first engaging students with it through the work of Elisabeth Schuessler Fiorenza, whose book, In Memory of Her (1983),5 introduced my generation of scholars to the hidden histories of women in early Christian texts. Schuessler Fiorenza insisted that you had to read between the lines, and sometimes just read the lines critically and carefully, to see what years of patriarchy had obscured from view. This ancient creed is a good example of how her methods could bear fruit.

If you read the third chapter of Galatians, you’ll barely notice the creed. The chapter is all about faith, and how faith has replaced the need for the Jewish Law. Paul brings in the creed to shore up his idea that the Law no longer separates Jew from Gentile—“there is no Jew or Greek.” The other parts of the creed—“there is no slave or free,” “no male and female”—are irrelevant to the argument and scarcely register. But if you pause long enough to examine Galatians 3:28 carefully, you quickly see its formulaic qualities. You might even guess that it was a creed of some sort. (In the book I do a methodical close reading of the text to unearth the whole creed from its textual surroundings.) The point is, this creed is part of a hidden history, but not just of women and gender. Here was another take on slavery quite radical for its day. And “there is no Jew or Greek” was perhaps the most challenging claim of the three.

As I began to think about this creed more and more over the years, it gradually occurred to me that if it was actually a pre-Pauline formula, then it would belong to the earliest attempts to capture in words the meaning of the Jesus movement. There are no Christian writings older than Paul’s letters. Therefore, anything embedded in these letters could lay claim to the title of “first.” Was this the first Christian creed? Arguably, yes. What does Christianity have to say about race, class, and gender? Everything, apparently, at least originally.

Before Revelation made Christianity a set of arcane apocalyptic predictions; before the gospels told the story of Jesus as God’s persecuted righteous Son; before Paul could argue that human beings are justified by faith, not by works of the Law—before any of that, there was first this elegant credo and the utopian vision it contained. It says nothing about theology proper. It asks one to believe nothing about God or the nature of Jesus Christ, nothing about miraculous births or saving deaths, nothing about eternal salvation. It says everything, though, about identity. We human beings are naturally clannish and partisan: we are defined by who we are not. We are not them. This creed claims that there is no us, no them. We are all one. We are all children of God.

In Christ Jesus. Ah, the caveat! Daniel Boyarin, the last scholar to explore this creed in great depth, would be eager, and right, to point this out.6 Boyarin, an Orthodox Jew, urged caution before we all go running off down the road to the utopia where all are one. “There is no Jew or Greek” in Christ Jesus just means that there is no longer Jew. Unity under the banner of Christ may sound good to everyone already under the banner of Christ, but to those who are not and do not wish to be, “we are all one in Christ Jesus” sounds more totalitarian than utopian. Quite so. Boyarin was concerned mostly about Paul, who wrote these words into his Epistle to the Galatians, and about the long-term impact Paul turned out to have on Western civilization, especially for Jews. But again, Paul did not compose the creed. He borrowed it, and in so doing, he changed it, adapted it.

For Paul, indeed, it was all about being “in Christ Jesus.” But those words are part of Paul’s adaptation of the creed, not the creed itself. On the face of it, that must surely sound like special pleading. Believe it or not, though, there are very sound critical arguments for saying this, which I lay out in the book. But even without these scholarly gymnastics, one can see that the creed was not originally about cultural obliteration. “There is no Jew or Greek” stands alongside “no slave or free” and “no male and female.” These are not distinctions of religion and culture, but of power and privilege.

In the world of Greek and Roman antiquity, free men had power and agency, slaves and women did not. The creed was originally built on an ancient cliché that went something like this: I thank God every day that I was born a native, not a foreigner; free and not a slave; a man and not a woman. The creed was originally about the fact that race, class, and gender are typically used to divide the human race into us and them to the advantage of us. It aimed to declare that there is no us, no them. We are all children of God. It was about solidarity, not cultural obliteration.

I live my life on a college campus, where a claim like this is really not so remarkable. In fact, it is a place so comfortable and proud of its ideals of inclusion and acceptance that we have already pressed on into increasingly finely tuned postmodern explorations of the limitations of oneness and solidarity. In that sense, what I lay out in the book may seem just a tad quaint to those on the leading edge of this conversation. I put the finishing touches on this manuscript, though, in the aftermath of a historic American presidential election in which the newly elected president rode into office by telling white, middle-class Americans who their enemies really are: foreigners, who are taking their jobs; the poor, who are soaking up their tax dollars on the public dole; and women, who do not know their proper place.

This message found a special resonance with Christians, most of whom voted for him: 58 percent of Protestants, 60 percent of (white) Catholics, 61 percent of Mormons, and 81 percent of (white) evangelicals. White evangelicals made up more than 25 percent of the American electorate in 2016. Without their record turnout and overwhelming support, Donald J. Trump would not have been elected president of the United States. Suddenly, we find ourselves living in a white Christian nation, in which race, class, and gender do matter after all. Difference does matter. There is an “us” and a “them.” How far we will go down this road to fascism is, for now, anyone’s guess. Are we fools now to fear the worst, or will we become fools to our descendants because we did not worry more?

Whatever the future holds for our little world, with its big fish like Trump, it is time now more than ever to tell the story of this forgotten first creed. History reminds us again and again that it has always been easier to believe in miracles, in virgin births and atoning deaths, in resurrected bodies and heavenly journeys home, than something so simple and basic as human solidarity. The Forgotten Creed, then, focuses on an episode of our history from a time long past, when foreigners were slaughtered, captives sold as slaves, and women kept in their place, when a few imaginative, inspired people dared to declare solidarity between natives and foreigners, free born and slaves, men and women, through a ceremony and a creed. It is the story of that first, unbelievable creed.

***

1. “Die Frauen in die neutestamentliche Schriften,” Theologische Quartalschrift 90 (1909): 321–51.

2. Heinrich Weinel, Paulus. Der Mensch und Sein Werk (Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr [Paul Siebeck], 1904), 212–15.

3. Larry Hurtado, Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003).

4. Everett Ferguson, Baptism in the Early Church: History, Theology, and Liturgy in the First Five Centuries (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2009), 147–48.

5. Elisabeth Schuessler Fiorenza, In Memory of Her: A Feminist Theological Introduction

(New York: Crossroad, 1983).

6. Daniel Boyarin, A Radical Jew: Paul and the Politics of Identity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994).