From my vantage point across the aisle and a few rows back, I studied Cardinal Francis George’s reaction when our Alitalia flight bound for Pope John Paul II’s funeral in Rome hit the kind of turbulence that makes most travelers grip the armrest and offer involuntary prayers.

Cardinal George held a copy of a broadsheet Italian newspaper in his hands, arms bent at a 45-degree angle as he casually read coverage of preparations for the conclave to elect John Paul II’s successor, in which he would vote for the first time.

When the 767 airliner jostled and dipped like a possessed carnival ride, Chicago’s cardinal didn’t budge—nary a flutter of newsprint. In fact, he seemed blissfully unaware of any tumult, real or imagined.

That is a man secure in his mortality, I thought as I craned my neck to look for the flight attendant refilling wine glasses.

I recalled that unflinching newspaper when I learned Cardinal George had died last week after a lengthy battle with cancer, a disease he’d beaten twice before in the years since I left Chicago and the newspaper job that often put me in his company—whether I’d been invited or not.

Cardinal George (or “Frannie G,” as some of us media creatures used to refer to him, affectionately) was a tough nut to crack. He could be stern and officious, and occasionally he seemed to take pleasure in pointing out the ridiculousness or implausibility of questions asked by various journalists while the cameras (and tape recorders) were rolling.

He could behave as if he thought he were the smartest person in the room (in fairness, he often was). Early on in his tenure as Chicago’s cardinal-archbishop, George could wear intellectual arrogance like a medal of valor. Sometimes his head got in the way of his heart, and he was perhaps not as pastorally gifted as his predecessor, the beloved Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, had been.

And yes, he did bear a striking resemblance to Montgomery “Release the Hounds” Burns.

But Cardinal George was more than the caricature of a curmudgeonly, conservative Catholic prelate, or an out-of-touch shepherd confounded by contemporary culture and the actual lives of his flock.

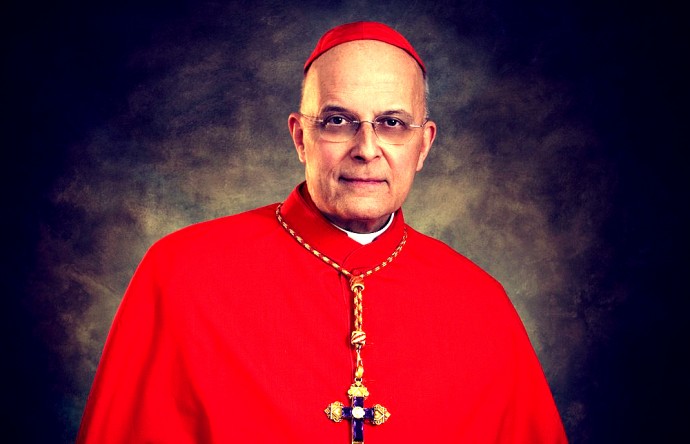

Cardinal Francis George of Chicago at the inauguration of Mayor Rahm Emanuel, May 2011. Photo by Photobra/Adam Bielawski via WikiCommons

During my decade as the religion writer for the Chicago Sun-Times, I spent a lot of time with the cardinal in Chicago and abroad. In fact I probably wrote more words about Francis Eugene George than anyone else.

We had our disagreements, some of them quite public. Yet despite our differences—and they were doctrinally, philosophically, and culturally legion—we developed a mutual respect and genuine affection for each other.

While I was born into a fairly devout Roman Catholic family, my immediate family has identified as Protestant since I was 10 years old when both of my parents became born-again Christians and left Catholicism for (of all things) the Southern Baptists. All of my extended family, including the family into which I married, remains Catholic and, despite worshiping with various Protestant and Anglican communities over the years, I still find meaning and a certain comfort in some aspects of Catholic liturgy and tradition.

Whether I was or am Catholic never was a source of tension with Cardinal George. But what might have been was his no-room-for-discussion position about some Catholic doctrine and social teaching on, for instance, the ordination of women, homosexuality, and birth control. And, while it wasn’t official in any canonical way, I disapproved of the way the Catholic hierarchy (in Chicago and universally) treated victims of clergy sexual abuse. Both have improved in recent years (although full repentance and reconciliation remain elusive), and Cardinal George provided much-needed leadership in 2002, when he pushed his fellow American cardinals and the Vatican to pass particular canon law for United States church that demanded zero tolerance in cases of clergy sex abuse. Still, his personal pastoral response to the emotional and spiritual needs of clergy abuse victims was not what it might have been, at least not in the early days of the scandal.

I held Cardinal George’s feet to the flames on many occasions and often wrote things I’m sure he wished I hadn’t, not least of all his 2006 mishandling of the case of Daniel McCormack, a young, rising star among Chicago priests whom the cardinal refused to remove from ministry when accusations that he’d molested two young boys at his parish school first surfaced. McCormack ultimately was convicted criminally of molesting five children. The cardinal apologized for his inaction, telling reporters after McCormack’s arrest, “I’m saddened by my own failure, very much so.”

My role as a reporter was clear: it was my responsibility to keep any personal biases (religious, political, or otherwise) in check and not allow them to color what or how I reported. I covered Cardinal George as vigorously, fairly, and accurately as I could. But it didn’t mean I had to like him.

At first I didn’t. But then I got to know him.

Sure he could be acerbic, and even a bit imperious, but he was no misanthrope. One of the things I remember fondly about the cardinal was his huge, easy smile and and infectious laugh. It was that laugh—practically guileless, like that of a happy kid—that most belied his popular nicknames such as “Francis the Corrector” or “America’s Ratzinger.”

He was kind to me and to others. When my father was battling cancer (not long before the cardinal himself was diagnosed) George rarely missed a chance to ask after him. When he saw me for the first time after I’d shed a few pounds (on purpose), he looked me straight in the eye and asked if I was OK. “Are you sick?”

And then there was the time in Rome when I’d lost my wallet to a pickpocket. How the news reached him I still have no idea, but when he spotted me across an international media scrum outside the Vatican press office, he shouted, “Cathleen, are you alright? I heard you were robbed. Do you need some money?” (I could have died of embarrassment but he was so dear, it was hard to be cross with him for offering me cash in front of the world’s press corps.)

The cardinal was candid, a trait that frequently got him into trouble and was more than once his saving grace, and that I, as a journalist, applauded. He didn’t dodge questions (or sneak out the back door, to avoid the media as a few of his brother cardinals did at the zenith of the clergy sex abuse scandal). He also didn’t lie to us (at least not as far as I know), which is an all-too-often rare experience among religious leaders, whether in the throes of crisis or not.

For many years as a religion journalist, and even as a columnist where I was supposed to offer my opinion and perspective, I kept my own spiritual and religious predilections to myself lest I appear biased toward or against one or another religious group or idea. A few of my sources told me there even was a running bet among Chicago’s Council of Religious Leaders (which included the cardinal) about my true religious identity, which wasn’t shocking in a city where religion is a spectator sport just as much as football, basketball, or baseball. (Go Cubs!)

But to the best of my memory, Cardinal George never asked me which team I was playing for, spiritually speaking. When I eventually outed myself as a graduate of Wheaton College (and, hence, at least at one time, an evangelical Protestant) he never mentioned it, nor did he comment when I wrote about having made my First Communion, the fact that my great aunt was a Sister of Mercy, or that my family had left his church when I was in grade school.

The cardinal knew I held an advanced degree from seminary where I’d studied religious history and theology. He once remarked that he liked not having to “translate” church teaching or ideas for me the way he felt he needed to with some of my colleagues. He appreciated that, and I appreciated him for recognizing it. Dogmatically we likely agreed on little else beyond Jesus himself. But Frannie G didn’t inquire about specifics and he never gave me cause to suspect he presumed we were ideological comrades or adversaries.

An introvert in an extrovert’s job, Cardinal George was deeply caring, something that wouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone had his public persona more accurately reflected the actual man. (A dear friend in Chicago who also covered the religion beat and frequently butted heads with the cardinal as she followed him around the world for more than 15 years, received a letter from him on the day he died thanking her for her journalistic service and her “many kindnesses” to him, as well as offering what would be a final blessing to her and those she loves.)

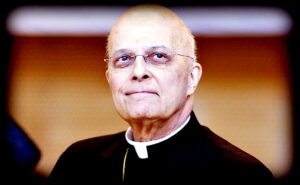

Cardinal George leans on his bishop’s crozier during a mass in Chicago. Photo via the Archdiocese of Chicago.

Above all, he was a deep thinker. About the philosophies he studied, earned one of his two doctoral degrees in, and taught as a college professor. About the improbable arc of a life that took him from a teenager hobbled by polio and rejected by his diocesan seminary because of it; to the head of his religious order—the Oblates of Mary Immaculate—living in Rome for a dozen years and traveling to some of the world’s most fraught places; to his rise from bishop of Yakima, Wash., to archbishop of Portland, Ore., to cardinal-archbishop of Chicago. And about faith—his, and that of others.

Patience was not one of the cardinal’s strong suits, a fact he was the first to admit. He didn’t suffer fools gladly, especially when they were members of his own flock who were, in his view, doing it wrong. “That’s one of the biggest difficulties. I get impatient at times,” he told me years ago. “I try not to, but when you’re faced with something that you know just isn’t so, and you say, ‘Well, that’s not so!’ You try to be polite, but people should know better,” he told me once as we discussed what he called “wrong ideas about God.”

“Christ is not an idea. Christ is a person. But ideas about him are very important. If you have a wrong idea, that stops your growth in God,” he said. “People within the church should know better and just are ignorant of the facts, no matter what you think about them. That puzzles me.”

In our many conversations over the years, it was clear to me that Cardinal George was much more interested in his place in eternity than in history.

“At each turning, there’s a call,” he told me not long before entering the first of two papal conclaves he’d vote in before his death. “You have to see it as a call, and with God’s grace, you do. And I have to say, I have. But I still have the question of why this call and not another.”

“Nonetheless, each time there is a response to a call, you see a different dimension of Christ,” he said.

While it’s been a number of years since I last wrote about him or had occasion to visit with him, the cardinal remains one of my favorite subjects as a journalist and was, particularly in hindsight, an unlikely—and truly cherished—friend.

Cardinal George had an abiding faith. Not the kind of faithiness that might be a point of pride, but the down-deep-in-his-bones kind of faith that is a gift, a gift he about which he was ever cognizant and grateful.

“My introduction to Jesus was as a loving savior whose own suffering rescues me from my sinfulness,” he told me, “and therefore enables me to live with him and the Father and the Spirit forever, and all of his friends”

News of Cardinal George’s departure from this earthly realm broke my heart more than a little. But as his life is celebrated today in a funeral mass at the Chicago cathedral where he presided for 17 years, I am thankful for having known him and that he has arrived on the other side of the veil to take his seat among the Great Cloud of Witnesses.

Requiescat in pace, Frannie G.