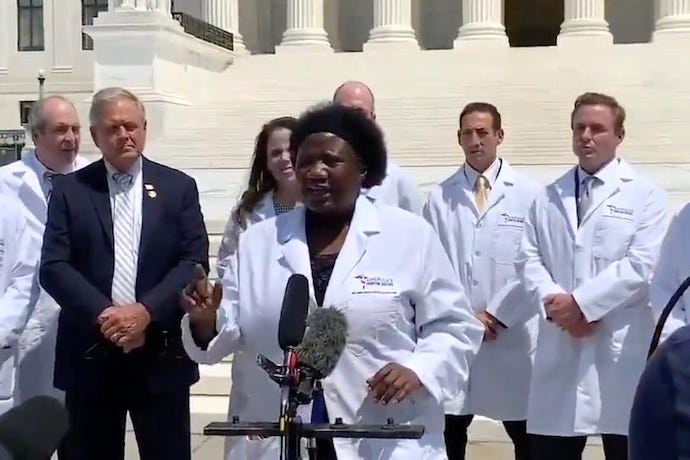

On Monday, in a since-deleted tweet, President Trump shared a video of Houston-based, Cameroonian-American doctor Stella Immanuel touting the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine for treating COVID-19. On its own, of course, there’s nothing particularly newsworthy about this; the President has been touting the anti-malarial drug for months now, despite the fact that it almost certainly doesn’t work. It’s also unremarkable that the President is contradicting the consensus position of the scientific and medical community, for he’s been doing that for months as well.

What really seems to have made this tweet rise to the surface in the morass of the U.S. news cycle are Immanuel’s apparent convictions about sexual liaisons with demons and conspiracy theories involving alien-DNA. What would almost certainly shock people even more is to learn how many evangelicals in the U.S. and around the world share the perspective of Trump’s new favorite doctor.

This religious perspective, which understands the world to be contractually bound to Satan and his demons and in a perpetual state of spiritual war, has a distinctly American history but in recent decades has become a global religious phenomenon. It’s a movement Fuller Theological Seminary professor C. Peter Wagner called the “Third Wave” and for which he helped to lay the groundwork in the late 1970s and early 80s.

Sometimes identified through its specific movements like the “New Apostolic Reformation,” and other times as a part of more general trends like “neo-charismaticism,” this style of evangelical Christianity has come to characterize a wide range of global Christians which includes everything from Pentecostals to charismatic Catholics. Terms like “prayer warrior” and practices like “strategic level spiritual warfare” are the usual markers of this denominationally diverse movement.

Born as it was in the context of U.S. missiology and “church growth” theory, it’s been built from a distinctly global set of cosmological perspectives. The demonic spirits that U.S. missionaries once seemed to detect primarily in cultures of Africa and the African diaspora, traveled back in the stories and accounts of missionaries and helped to construct a thoroughly possessed American cosmological perspective. The discourse of spiritual warfare has become a kind of international Christian dialect.

Still, whether one knows much about the movement or not, no one should be surprised to find its views trumpeted from the highest office in the land. In 2011, the New Apostolic Reformation hosted a prayer conference featuring former Secretary of Energy, Rick Perry. Perhaps an even nearer comparison can be found in former Alaska Governor and 2008 Vice Presidential candidate Sarah Palin, whose videotaped “deliverance prayer” with an African exorcist drew media scrutiny at the time. Third Wave spiritual warfare, with its firm conviction that the world is profoundly influenced by demonic forces, has, in real social and material ways, been traversing the halls of powers for more than a decade.

Trump’s decision to tweet Dr. Immanuel’s words, then, likely reflect more calculation than most media will grant. Most obviously, Dr. Immanuel lends professional credence to his original claims about hydroxychloroquine being an effective treatment for COVID-19. Simply put, he found a doctor that agrees with him. However, given the protests and demonstrations that have accompanied this long summer, it’s surely not insignificant that Trump has chosen to valorize a doctor who is both a Black woman and an African immigrant. Most important, though, is to recognize the way that spiritual warfare as a cosmological perspective fuels the engines of the kinds of conspiracy theories in which Trump loves to dip a toe (or both legs).

In my own research with spiritual warfare Pentecostals in Haiti, the “prophets” and “prophetesses” who lead their communities frequently remind me that “there is always more than you can see.” When congregants come to them for healing from what appears to be an obvious medical condition like a tumor or tuberculosis, they unfailingly diagnose them with a spiritual affliction from one of a number of malevolent spirits. If I protest out of concern for the sick person, which I will admit I have done, they remind me that “doctors cannot see everything.”

For Haitians, of course, there’s hundreds of years of history to support the sense that the “experts” don’t always have their best interests in mind. The pervasive corruption of state leadership and the pernicious impacts of international interventionism in recent decades have served only to heighten this sense of distrust.

For many U.S. evangelicals, though, the profound recent sense of insecurity wrought by the global pandemic, civil unrest, and economic uncertainty have inflamed a distrust of the “experts” that’s been latent since at least the Scopes “monkey trial” and debates over the teaching of evolution in public schools. In this time of profound crisis, as the political left reacts to the anti-intellectualism of Trump’s White House by valorizing science and the experts, the president is strategically aligning himself with a doctor who believes that demons can cause physical illness.

The real surprise, I suspect, will be the effectiveness of this politically calculated move that no doubt appeals to the fastest growing movement of Christians in the world, and we should have seen it coming. After all, Trump has been warning us for several weeks that Dr. Fauci cannot see everything.