Sarah already pointed out some of the problematic aspects of the most recent of the paeans to civility put forth by Chuck Colson and Jim Wallis in Christianity Today.

Look, conviction, dialogue, respect, humility, yes, whatever. All very important and laudable. Also unworkable, as it turns out. Colson and Wallis deplore “demonizing” political opponents, and call for Christians in the public square to respond to the image of God in one another:

That means that when we disagree, especially when we strongly disagree, we should have robust debate but not resort to personal attack, falsely impugning others’ motives, assaulting their character, questioning their faith, or doubting their patriotism.

Sarah dealt with the obvious lack of equivalency in her post earlier today, detailing some of Colson’s uglier words and associations.

But it’s also important to point out that one person’s “demonizing” is another’s truth-telling. Put it to you this way: if I say Chuck Colson is a dishonest, quasi-theocratic cultural warrior who hangs around with creepy, semi-fascist extremists and who never quite shook the habit of being a partisan hatchet man, is that a personal attack, or simply reporting the facts, albeit bluntly? And if I wonder why it is that Jim Wallis is palling around with a guy who likes to compare liberals to Nazis—not once, but repeatedly—is that questioning his motives, or is it raising a legitimate concern about his role as spokesperson for liberal or progressive religion?

Conservatives will no doubt raise all kinds of counter-arguments (Keith Olbermann, Markos Moulitsas, etc., etc.), but this only proves my point. As long as there are disagreements in the public square, there will be “incivility.” That’s just human nature, and to a certain extent, it’s good and healthy. It means that people are taking things seriously.

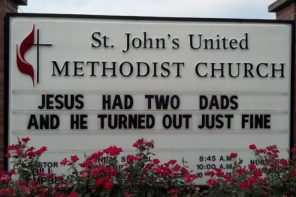

And all of this is even before we bring in the “God stuff.” For one thing, I don’t remember the God of scripture being much interested in compromise. (See: Pharaoh, hardening of heart.) If you read the Bible carefully, it’s true that Jesus often speaks softly, but it’s equally true that God’s plan of redemption comes over and against the plans of the world, rather than emerging from consensus with them. If you don’t believe me, you need to go back and read the gospels, and Paul’s polemic, and James, and Revelation, and the prophets, and Genesis and Exodus…

This of course doesn’t excuse any and all forms of nastiness in the public realm. It does indicate to me at least that truth comes out in struggle as often as it does in well-mannered dialogue. We need both. It is not good for our democracy nor is it particularly godly to rush to suppress real conflicts. Or, to paraphrase Tony Campolo, if you’re more concerned that somebody said “wanker” than you are that our democracy is circling the drain, you’ve got a problem.

Last point. All of this feel-good talk about conviction and civility is premised on the notion that if only individuals improved their behavior, we could have a nicer public square. That is to say, it diagnoses the problem of incivility as people being mean to one another. That’s part of it, I’m sure. But as Walter Brueggemann understands, “The first enemy of hope is silence, civility, and repression“:

Where grief is denied and suffering is kept isolated, unexpressed, and unprocessed in a community, we may be sure hopelessness will follow. Silence may come because this sufferer lacks the courage or the will to speak. But behind that, I submit, is the long-term pressure from above. The rulers of this age crave order above all. They have learned that silence is the way to preserve order, even if that order is unjust and dysfunctional. Where there is no speech about grief and suffering, there can be no hope.

Often that speech about grief and suffering comes out in rude, even violent or threatening ways. As much as I deplore the violent jingoism of the American right, I have no doubt that behind it lies real pain and fear. We would be fools to treat the symptom (incivility) without looking at the disease (grief and suffering). Furthermore, we would be fools to offer a prescription (politeness) that doesn’t address what truly ails us as a nation:

Temptations to terror, conformity, and absolutizing are all of a piece. They breed in contexts where there is no prospect of a future that will be different from the present.

What drives the viciousness of our current politics is not that some people are wankers—excuse my French—and need to improve their behavior, but that the vast majority of citizens, whether on the left or the right, perceive that their political leaders have failed and continue to fail to provide a meaningful future for them and their children. Solve that problem, and you’ll solve the problem of our discourse. Until then, spare me the lectures on civility.

Brueggemann quotes from Hope Within History, (John Knox Press, 1987).