If the mass killings in Orlando and in Charleston have anything in common it’s that both the dance club and the church were thought to be “safe space.” The horrors that unfolded in both places tell us that no place is truly safe—but marginalized communities will still gather and claim sacred space for themselves, no matter the risk.

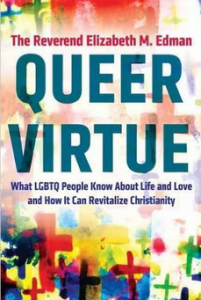

This spirit of risk—to be able to be both authentic and remain hospitable to strangers—is the message queer people bring to the wider church, according to the Reverend Elizabeth M. Edman, an Episcopal priest and author of the new book, Queer Virtue: What LGBTQ People Know About Life and Love and How It Can Revitalize Christianity.

Queer Virtue: What LGBTQ People Know About Life and Love and How It Can Revitalize Christianity

Elizabeth M. Edman

Beacon Press

May 2016

I recently spoke with Rev. Edman about loving God and neighbor in church, in our communities—and on the dance floor.

Candace Chellew-Hodge: Why did you write this book, and what kind of impact do you hope it will have?

Rev. Liz Edman: I hope the book will make some inroads into the homophobia, bi-phobia and transphobia that continue to live and breathe throughout the world. My book is focused on Christianity in particular, but I would hope some of the ideas raised would reach beyond the Christian tradition and give people of a good heart some language to start new conversations about human sexuality.

The book does lift up queer ethics as a model. What I see going on in the queer community—and certainly as it was at Pulse—is that we dance. We model a kind of strength that exudes joy, that is very physical, but involves physical vulnerability. In some ways dance is our biggest “weapon” in our arsenal for justice. We find love, joy and community on the dance floor.

To me, that gestures toward the transcendent.

Candace, you wrote a book on what it means to be “bulletproof,” To me, that’s recognizing that people can come in with an actual gun—but there is something that we’re living here that survives even that. Love demands vulnerability, and we live it every day.

Scripture calls us to rely on God alone—not on some weapon, not on some empire. The queer people dancing at Pulse were witnessing to God’s love. They were following God’s demands far more than (nominally) Christian politicians who are influenced by the gun lobby.

The church can learn from queerness. In the book I’m asking: how does the queerness of our tradition inform who we are called to be?

The word “queer,” that’s one of the pejoratives that we have reclaimed. What does that mean to you, and how do you pair queerness with virtue?

The community has reclaimed the word “queer,” partly to get us away from the alphabet soup of myriad sexual identities that people are now claiming and embracing. It’s an umbrella term to refer to people who live outside of conventional heterosexual relationships and lives.

I use it as a shorthand reference to the discipline of queering. Queer theory is rooted in the urgent demand to dismantle certain binaries—specifically male and female—as definitive poles. I’m using queering as a verb and looking at all the ways that I see Christianity rupturing binaries in surprising, provocative ways. For example, in his person, Jesus queers lines between human and divine; in his work, Jesus queers the line between sacred and profane; and in his resurrection, Jesus queers the lines between life and death.

Then you’ve got these extraordinary stories about Jesus where he’s reaching out to people in a healing narrative. When Jesus talks with people about who a neighbor is, he is calling his followers to queer their conceptions of self and other. He told stories that flipped roles around, to get people to perceive that they weren’t in opposition to one another.

In The Letter to the Galatians, Paul calls on people to dispense with the idea of separation. You are no longer Jew or Greek, no longer slave or free, no longer male or female. He’s trying to queer conceptions of who we are to each other—and who we are in relationship to God.

Right, because Jesus is not either/or, he’s a both/and…

Virtue in Greek philosophy is the idea that you can practice living an ethical life. I’ve observed the ethical path I see queer people walking. We have to be very honest with ourselves and with other people, sometimes at a real personal cost. We have a pretty good track record of looking to the margins and seeing who is not included. That ethical path is tied directly to our queer identities, very much informed by this idea of queered binaries.

It’s not a surprise to me that this ethical path bears a resemblance to the ethical path that Jesus asked his followers to walk. I see an opportunity for queer people to help Christians perceive the queerness in Christian ethics and help us walk it better.

For LGBT people in church, our queerness forced us both to figure out what we believe, and why we believe it. We’ve been forced to create a queer ethic where none existed before.

I’ll use your own book as a point of reference again, Candace. You talk about developing a bulletproof faith—which has everything to do with spiritual survival. Yet one of the ways you talk about surviving is in understanding your own value. Then when someone comes at you, show them the dignity and respect they ought to be showing you.

One could say we’re “forced into” living this way as a matter of survival, but the truth is we’ve gotten really good at it. I’ve seen us treat each other that way again and again when nobody was holding a gun to anybody’s head. That’s just virtue at work. We don’t always do it. We’re not even close to 100 percent, but I’ve seen it more consistently in the queer community than in any other kind of community I’ve ever been part of—including the church.

What would the church look like if it embraced queer virtue?

There would be a lot more people in the pews right now, because it would be a place that fed people more deeply, that challenged people more vigorously, that engaged people in an exciting way.

Our witness would be more authentic. Across the board, church would be a dynamic place to be because it would be a community you’d want to be part of.

That reminds me of something I encountered years ago. A drag queen and her two backup singers sang country gospel every Sunday night at a gay club in Atlanta and the place was always packed. People sat on barstools drinking beer, smoking cigarettes, and praising God. They knew all the words, and they smiled and danced while they sang. They were enraptured, taken over by their joy. They were worshiping. That bar was church.

I can’t help but think that it’s like this even in our “secular” spaces. When queer people come together, they create a community that is alive. It’s made up of individual people, but it’s one body that moves. When you are part of it, you don’t lose yourself as much as you become more somehow.

Within progressive, mainline denominations, I see vast potential for that “more” you’re talking about—more energy, more enthusiasm, deeper commitment and involvement.

In other traditions, particularly where there is a strong evangelical fervor, there are places where worship is amazingly alive. People go to church and are there for hours on Sunday. Imagine what it would be if you could take the energy of an evangelical church experience or African American church experience, and marry that to the dynamism of the queer experience of that dance floor. It would be amazing.

Many mainstream or evangelical churches may welcome you into the pew but never into leadership or other forms of service. You’re calling the church not simply to affirm LGBT people, but to fully accept us.

I’m asking the church to dismantle that binary of “us” and “them” that sees anyone coming through the door as an other.

My hope would be that [churches] learn to do that not just by trying to understand the queer experience, but that churches that are predominantly white would begin to see through the eyes of people of color. And people who have strong roots in a particular place might try to see what it’s like to be an immigrant. What is that experience, and what has that experience taught that person about God?

For people in the church who operate from a place of privilege, it’s hard to hear another person’s story about God without thinking, “Oh, that’s nice, but that’s not how God really is, or acts, or thinks,” even if the other person is talking about a lived experience of God. We tend to think of our own experience as the only experience of God.

Often when we hear somebody’s story, we tuck that away as just a story. That’s not the same thing as asking, “What do you know about God that you can teach me? You had to make that decision in the dead of night to pack up what you could, carry it and your two kids out the door, and race to meet that boat to cross the Mediterranean—not knowing whether you’d make it or not. What did you learn about God in that experience?”

If you listened to the witness of somebody who has had to make that decision, something in that would speak to some experience in your life when you were in danger—making a decision you knew affected the lives of the most important people in your world.

But too often faith emphasizes our differences.

It emphasizes being safe and secure and getting away from the dangers we face. In truth, a lot of people in this world are in danger all the time. Most of us are probably struggling most of the time.

Those who preach the prosperity gospel would say that if you don’t feel safe you’ve done something wrong or that God is punishing you. We’re taught that security is our birthright—if we’re faithful enough. When we see others living in insecurity, like refugees, we tend to wonder what they did wrong.

That’s right, but it gets worse—because it has direct implications for justice in the world. If you think that your physical security is a divine right, if you think that happiness is supposed to be normative in the world, then in moments when you feel insecure or unhappy you look around to figure out whose fault this is.

You also talk about risk in your book, and I believe our more conservative brothers and sisters believe that they are the ones who are taking all the risks in actions such as refusing to sign wedding certificates or bake wedding cakes. When they face backlash for this they feel persecuted for taking what they see as a principled stand. What do you say to them?

If you’re taking a kind of risk that inherently pits you against people—particularly people who live on the margins, people who have been disempowered—something is wrong there.

How can queer virtue start to tear down that “us” and “them” binary?

I find the idea of a path helpful here, one that is both a queer path and a Christian path.

You have to discern an identity, and you have to figure out what that means to you. Part of that is to develop a sense of pride in that identity—not one that is triumphant or that pits people against each other, but one that allows a solidarity to flourish. That’s the first step. The second step is to be willing to step into places of risk where you get honest about that identity with other people. You “come out,” but it’s not to change the other person. It’s about telling the truth of your own life. In the book, I lift that up as a model for Christian evangelism.

Risk leads you to connect to other people. That demands authenticity, and there is a lot in the book about how that informs power dynamics within community.

Finally, in the spirit of looking to the margins, we have to be willing to enter into places that are scandalous. You have to enter places of scandal where you’re willing to really own that stuff when it gets scary and when it defies conventional norms. That’s what Christians take on when we do outreach ministry and go into the margins to address injustice.

I understand that your grandfather on your father’s side, Victor Raymond Edman, was once president of Wheaton College.

Yes, he was actually Billy Graham’s mentor.

What do you think he’d make of all this?

I don’t know, honestly. He died when I was a small child, so I don’t really remember him. He died before this conversation had really begun to play out. I know that he was pretty conservative in his morality. Even though I suspect there are a lot of theological issues where my grandfather and I would disagree, I don’t know that for a fact. I don’t know what would have happened to his heart.

My one hope would be that he would appreciate this lesson that I took from his life and from his wife, my grandmother. They were evangelical Christians, and in their time, what they were preaching was unpopular. My mother’s parents were journalists and preachers in Arkansas, also often writing and preaching messages that were unpopular for opposite reasons.

From both sides of my family, I learned that it matters to tell the truth as you experience it whether that makes you popular or not. That sensibility made it possible for me when I was a teenager to come to terms with my own sexuality because it was clear to me that this was the truth of who I am.

So often, queer people are defined by our opponents by our sexual acts and not by our full humanity. If we’re sexualized, we are more easily dismissed. Sometimes queer theology avoids talking about sex for that reason, but you don’t shy away from it in this book.

That comes from immersion in the Christian narrative. It’s what’s so jaw-dropping about Jesus. He’s the incarnation itself. The idea that God took on this human body blows me away. The truth is that sex is a huge part of the human experience—so much of what bolsters queerphobia and misogyny in society and the church is actually fear of sex. It’s a fear of talking about sex.

Sex is risky and chaotic. Sex can be scary. Just like encountering God can be chaotic and scary. There’s a lot of sex in the Bible! It’s there for a reason. That’s because nothing else in the human experience better captures what it means to encounter the sacred.