Religion is a frequent guest star on Bravo’s The Real Housewives franchise—who could forget Kyle Richards clutching her Zohar while caught in turbulence, Phaedra Parks’ exorcists and restoration services, or Ramona Singer’s True Faith jewelry line? But with the launch of the newest franchise, The Real Housewives of Salt Lake City, religion finally gets top billing. Andy Cohen and Bravo might be ready to get real about religion, but I have doubts about some of the show’s loudest fans. Can we talk about religion on RHOSLC without stumbling into perilous, essentializing traps?

Each of the six cast members are introduced in the series’ promotional trailer, a short clip of choral singing played beneath fast cuts of hot tubs and chairlifts and wine-throwing, along with their religion—Jen, a Mormon who converted to Islam; Meredith, a Jewish woman; Lisa, a Jewish woman who converted to Mormonism; Whitney, an excommunicated Mormon; Heather, a descendent of Mormon pioneers; and Mary, a Pentecostal minister.

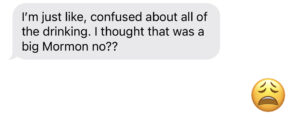

As the de facto expert on all things religious in my group texts, I’ve been fielding a lot of questions about the women of RHOSLC which orbit around a common theme.

“How can Heather be a Mormon if she’s drinking?”

Same question about Jen and her Islam.

Similar question about Mormon-convert Lisa and the many tequila brands she produces and hawks on the show.

“How can Mary make so much money from preaching? That has to be a scam.”

I love these questions. They’re religious studies lay-ups; easy entrées into a well-rehearsed mini-lecture: religion is complicated, messy, and often inconsistent or seemingly-hypocritical, because religion is a process, brought to life in the chaos of being human, something that transcends statements of belief and which must be understood outside of the pointless discourses of adjudicating what is a genuinely-held religious belief or a genuinely-performed religious identity. In short, religion is how it’s lived, not simply what its scriptures or leaders say it is.

The question of real religious identity and RHOSLC doesn’t just float around in the group texts of effete New York City gays like myself. Particularly Heather’s and Whitney’s plot lines deal explicitly with open and unsettled questions about what it means to be a real Mormon woman; both struggle with what they feel is a judgmental culture which enforces impossible standards.

Whitney had the Mormon hammer come down on her after her extramarital affair came to light, leaving her with some choice words for LDS authorities. Heather, whose beauty empire cashes in on, in her words, a Mormon obsession with bodily perfection, feels like she’s cast to the margins because she’s a divorcée who loves gays and tequila. These are not simple religious positions, and it is here where the show takes a very productive and provocative tack.

Real Housewives, as a franchise, is powered by the tension between a glamorous ideal and the chaotic real. Each cast member is doomed, through the fixture of the show’s gaze on the real-ness of their lives (however we are to understand that) to embark on the futile Sisyphean labor of achieving a Kardashian-ic apotheosis. In RHOSLC, an idea of a perfect and real religious performance joins the parade of impossible things expected of a fully-realized Housewife, situated somewhere between clearing out a Florentine Fendi and having the meanest, scariest glam squad.

In other arenas, solutions are ready at hand—one can just go and buy the newest Lamborghini or Birkin, and the rock is moved a little up the hill. But religion isn’t something one can be perfect at, and in their striving for religious real-ness, the cast members, particularly Heather and Whitney, are cluing us in to the hard lessons of lived religion.

But they’re only hard lessons because of the persistence of the real as a kind of taunting, ghost-like category; something spoken about as if self-evident, but has little weight when left standing on its own. What is real Mormonism, anyways? Islam? Christianity? Who gets to make that distinction, and what structures are in place which empower them to do so? And why do we, as observers and commentators and revelers in the franchise’s hairspray and chaos, feel compelled to stake out the real and wield it in our judgements, to insist on the possibility of the impossible?

Both Whitney and Heather make great strides in defanging the real through coming to terms with their own imperfections, Bravo be damned. Given proper care, RHOSLC can do a lot to push a public conversation towards a more nuanced understanding of religion, something scholars have been shouting from rooftops for twenty years, albeit without the aid of Andy Cohen’s cultural megaphone.

Unfortunately, it does not look like that’s happening (with the notable exception of The New Yorker’s recent coverage). Just look to the pithy weekly episode recaps written by Jezebel’s Shannon Melero for a glimpse into another judgmental culture which enforces impossible standards. Each week Melero gives the cast members a “Holiness Ranking,” measured in haloed emojis, derived from how closely a cast member’s behavior hews to the norms and ideals of a particular religious ghost.

Attempting to be tongue-in-cheek (beginning each post with an exhausting “Brethren and Sistren”), Melero’s insistence on making religion the perpetual butt of the joke leaves these posts oozing with the scorn of the neoliberal secular, the author taking clear pleasure from weighing the cast members against some notion of Islam or Mormonism—derived from what? I have no idea. Peruse at your peril, but here are some choice quotes:

“Lisa lost a halo for trying to use sage to cleanse her space—only Holy Father can do that, obviously—but got that halo right back when she sat in judgment over Whitney’s inappropriate twerking in front of other people’s husbands.”

“Sister Jen is struggling to align with the Muslim faith, but her attempt at a “modest” bathing suit has been noted. It’s not exactly going to get her to the front of the heaven line but it’s the thought that counts.”

“Whitney was up to her usual shenanigans this week with the drinking and swearing but also, giving her husband a lap dance in mixed company. Lap dances are not mentioned in the Bible or the Book of Mormon, but anything overtly sexual outside of the bedroom where marriage is really supposed to happen is generally frowned upon by the Holy Father.”

A few things at play here. There are notions of real and genuine performances of religious identities floating around within the show and within the commentariat. Melero might find herself shocked to be on the same side as the Mormon or Muslim authorities she clearly has so much disdain for in her own policing of proper religious performance.

In case it’s not clear, I’m frustrated that this is the kind of coverage RHOSLC is getting; that people aren’t able to apply what we already know about the impossibility of being a Housewife to the similarly-impossible task of being a Mormon or a Muslim. After all, why should we expect the real from reality television? Do we not, in the year of our lord 2021, know better than this? Shouldn’t our immersion in this genre, ironic or not, have taught us about the bankruptcy of the concept of the real?

To judge the Mormon-ness or Muslim-ness of the cast members of RHOSLC is to miss the point entirely, exposing a commitment to policing religion and confining it to a particular pasture of the public sphere. Enforcement and authorization are always in the background of invocations of the real, and I don’t think the discourse is served by falling back on this exasperating trope of white, privileged existence, by insisting that borders remain guarded and hypocrites thrown into the stockade. We can take a page out of the Housewives’ books. We can be more real.