It seems that all the Right wants to talk about these days is “grooming.” These accusations became popular recently in Florida with Republicans pushing for a law equating books about LGBT families with pedophiles grooming children. Governor Ron DeSantis’s press secretary, Christina Pushaw, made this explicit, tweeting: “The bill that liberals inaccurately call ‘Don’t Say Gay’ would be more accurately described as an Anti-Grooming Bill.” (The bill, signed into law in late March, prohibits discussion of LGBT issues in kindergarten through grade 3). But now talk of “grooming” is everywhere, from protests outside of Disney World to taunts yelled at LGBTQ people.

Many commentators have noted the similarities between this grooming language and the QAnon #savethechildren conspiracy, in which QAnon followers held rallies across the country seeking to save children from an imagined cabal of Democratic sexual predators. Yet this tactic goes back much further, to the emergence of the national Christian Right.

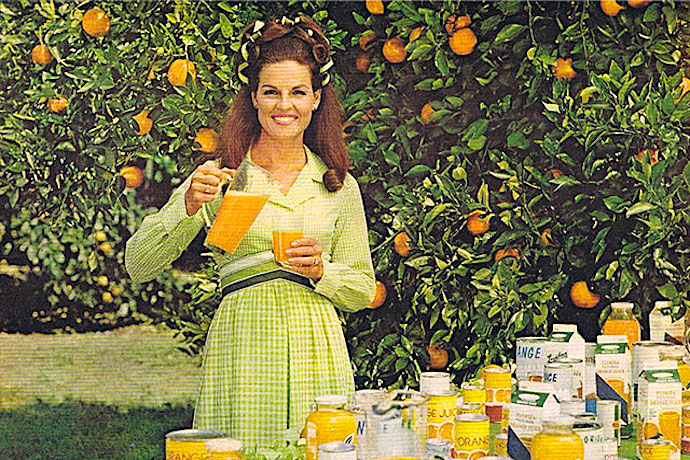

In 1977, former beauty queen and Christian singer, Anita Bryant, launched one of the first heterosexual rights campaigns in the US in response to a Dade County Commission decision to extend civil rights to sexual minorities. But instead of framing her organization as defending heterosexual supremacy, it portrayed gays and lesbians as threats to children. Her organization was even called “Save Our Children.” This tactic proved successful. The ordinance was soon revoked by voters and a favorite tactic of the Christian Right was born.

For 45 years Christian Right campaigns seeking to limit the civil rights of sexual minorities have instead framed their efforts as protecting children. A prime example comes in the form of opposition to trans rights bills, often called “Bathroom Bills” by Christian Right groups in order to ratchet up the fear, since they claimed that these bills would put women and girls at risk by allowing male predators into female bathrooms.

This tactic remains in play because it accomplishes so much. It works.

First, it shifts the conversation away from what these campaigns are actually doing by reframing supremacist movements as a defense of those who are powerless—children. Protecting children is far more popular than limiting the civil rights of a group of people. Polls show that support for same-sex marriage is at an all-time high, and that limiting LGBT rights is increasingly unpopular. So, instead of organizing around a narrative of defending heterosexual privilege and opposing the rights of LGBTQ people, this shift frames supporters of these bills as victims—or at least as defenders of victims.

This tactic also creates a moral enemy of one’s political opponents. Anita Bryant’s mantra, “homosexuals cannot reproduce, they must recruit,” rhetorically transformed gays and lesbians from human beings into a nefarious agenda. In this rhetoric, LGBT people aren’t citizens—not teachers, neighbors, parents—but a dangerous force. Today this tactic is being used not only to demonize LGBTQ people, but also anyone who supports LGBTQ rights. As DeSantis’s press secretary tweeted, “If you’re against the Anti-Grooming Bill, you are probably a groomer or at least you don’t denounce the grooming of 4-8 year old children.”

If you’re against the Anti-Grooming Bill, you are probably a groomer or at least you don’t denounce the grooming of 4-8 year old children. Silence is complicity. This is how it works, Democrats, and I didn’t make the rules.

— Christina Pushaw 🐊 🇺🇸 (@ChristinaPushaw) March 4, 2022

Third, this tactic serves to unite disparate elements of the right into an anti-democratic coalition. Opposing LGBT rights and framing children as needing protection brings white evangelicals and other conservatives into the same coalition, while providing a dangerous invitation for people across the conservative movement to demonize anyone who opposes them.

Take a recent headline from the American Conservative: “Democrats: Party of Child Mutilators and Kidnappers.” While clearly a nod to QAnon conspiracies it also points to an escalation in rhetoric that makes future democratic debate harder to imagine. Democracies can only be sustained through a belief in the legitimacy and fairness of the political process; seeing one’s political opponents as evil clearly indicates a loss of belief in the process, which is a bad sign for the sustainability of our democracy.

To be clear, this tactic is not actually about protecting children. RAINN, the largest organization in the US working to oppose and prevent sexual violence, provides evidence-based suggestions on the prevention of child sexual abuse. The guidelines are common-sense and speak to the need to monitor children’s use of social media and the caregivers they spend time with. Much of the guidance is on caregivers and parents being present to children and allowing them to speak about their needs and experiences.

It’s ignorance, not knowledge, that makes children vulnerable to sexual abuse. If the evangelicals helping to push these “Don’t Say Gay” campaigns forward were truly concerned about preventing child sexual abuse, and sexual abuse in general, they would be focusing more on their own churches and Sunday school programs which have “churn[ed]out…[a] generation of silenced victims,” according to former evangelical pastor Joshua Pease, writing in the Washington Post.

As an anthropologist who’s spent a significant amount of time studying white evangelical culture, I know very well that many evangelicals see heterosexuality and cis-gendered identities as requirements for living a godly life. In my book, The Divine Institution: White Evangelicalism’s Politics of the Family, I show how this fixation on heterosexuality links theology and politics, and has led to widespread ostracisms within the church of individuals who either come out as LGBTQI+ or who support LGBT rights.

Describing education about sexual diversity as “grooming” speaks to this evangelical focus on heterosexuality. However, equating exposure to the reality of sexual diversity to the actual experience of sexual abuse serves to both amplify the threat of LGTB rights and to belittle the trauma caused by actual sexual abuse. Not only that, but evidence appears to point to widespread sexual abuse happening within evangelical institutions, often covered up by patriarchal leaders.

In all of my research on evangelical culture in Colorado Springs, including sitting through dozens of sermons, Bible study conversations, and conducting around one hundred interviews, I rarely heard anyone mention the existence or possibility of sexual abuse taking place within the church. The current focus on LGBT “grooming” portrays threats to children as stemming from an imagined other, outside of conservative and evangelical circles, further obscuring the problem of abuse and making it that much harder to address.