any morning, any evening, any day

Maybe the sun is shining

birds are winging or

rain is falling from a heavy sky –

What do you want me to do,

to do for you to see you through?

this is all a dream we dreamed

one afternoon long ago

Walk out of any doorway

feel your way, feel your way

like the day before

Maybe you’ll find direction

around some corner

where it’s been waiting to meet you

~ from “Box of Rain”

“The Grateful Dead were more than just a band. They were their own planet, populated by millions of devoted fans.”

– Martin Scorsese

The Grateful Dead’s music has, for half a century now, provided a virtual “third place” for fans that have discovered companionship amidst the blithe, earthy sounds, sometimes spiritually-bent lyrics, and a subculture where the prevailing ethos landed somewhere between “take it easy, man” and “let’s take care of each other.

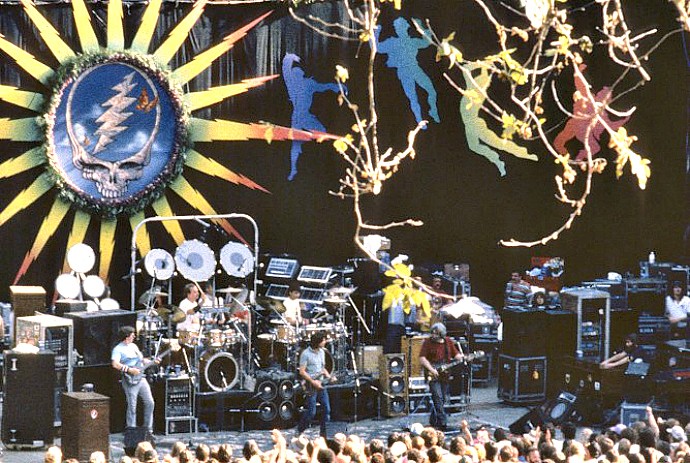

When Deadheads gather en masse for the band’s live performances—the last of which is scheduled for Chicago’s Soldier Field on July 5, at the same venue and almost 20 years to the day from the last show the Dead played while their chieftain Jerry Garcia was still alive— what was virtual becomes a physical third place, a festival where community, identity, and bonds of kinship are forged.

A special series on religion and culture produced in collaboration with the Office of Religious Life at the University of Southern California

While the location changed from concert to concert, Deadheads found the same spiritual camaraderie and community in whatever parking lot, field, arena, or festival grounds they found themselves in as they followed the band across the country and in some cases around the world.

Inside the sound, swaying and dancing and spinning with abandon, many of the Dead’s fans discovered something more transcendent than a blissed-out, good time.

They found belonging. Home. If only for a few hours, days, until the tour ended or the ticket dough ran out.

For many Deadheads, the sonic pilgrimage began when someone placed the needle at the beginning of song 1, side 1 of the Dead’s seminal 1970 album American Beauty.

I can’t hear the album’s first track—”Box of Rain”—without thinking about Lindsay Weir in what (sadly) became the final episode of Judd Apatow and Paul Feig’s brilliant, too-soon-gone television series Freaks and Geeks.

Set in 1980-81 in suburban Detroit, Freaks and Geeks revolved around the social circles of teenage Lindsay (Linda Cardellini) and her younger brother Sam (John Francis Daley). She’s a junior, he’s a freshman. Her friends are the “freaks” and his are the “geeks.” When we first meet Lindsay—an exemplary if languorous student all-star “mathlete”—she is beginning to question what she’s been taught by her parents, her schools, and her church. After Lindsay’s grandmother tells her, moments before she dies, that she sees “nothing” on the “other side,” Lindsay proclaims her nascent atheism, dons her father’s old green Army jacket, abandons her nerdy cohort, and befriends a group of fringe-dwelling students we might generously call “outliers” today, but who were summarily dismissed as “burnouts” and “freaks” back in the day.

Lindsay is a good girl, smart, acerbically funny but inherently kind. She’s also endlessly curious and mildly terrified about the world outside the borders of Chippewa, Mich.

As she progresses through her junior year, struggling to uncover her authentic self, she begins to fear that her life somehow is already scripted, and she’s doomed, perhaps, to be her mother’s successor in suburban domesticity. She’s not floundering, per se, it’s just that those first few steps out of the chrysalis can be awkward.

You know that tired Theosophist proverb (often wrongly attributed to the Buddha and/or his followers) that says when the student is ready, the teacher will appear? As Lindsay hurdles toward her senior year—and a summer consumed by an “academic summit” at the University of Michigan—her teacher does just that.

In truth, Jeff Rosso, her guidance counselor, had been there all along, paying attention and flashing the peace sign with his long, aging hippie hair and Hush Puppies. It just took the right words at the right time for Lindsay to notice.

“Maybe you’re tired and broken?” Rosso asks Lindsay as she slouches and cringes. “Your tongue half-twisted with words half-spoken and thoughts unclear? What do you want me to do? To do for you, to see you through?”

“Why are you talking like that,” she asks, clearly flummoxed by his bizarrely lyrical line of questioning.

“Just quotin’ the Dead,” Rosso says. “I know it always makes me feel better.”

“The who?” she says.

“Not The Who,” Rosso laughs, making a pun lost to her laconic teen angst. “The Grateful Dead. When I was in college, back in the early 1700s, I’d put their album American Beauty on whenever I was stressing out. It always helped….You know what? I’m gonna loan it to you. Put it on while you’re studying for finals and soon you’ll be raring to go to that academic summit.”

Lindsay is skeptical. But she takes the vinyl album home and soon we see Lindsay in her bedroom as the opening lines of “Box of Rain” play on the HiFi. She stares at the ceiling, out the window, and finally turns her gaze toward the stereo.

Slowly the music pierces the emotional body army she wears like her ubiquitous, oversized Army jacket, and Lindsay rises, reaches for the album cover, reads the liner notes, leans over, picks up the needle, and starts to listen to the song again. And again. And again. Now she’s dancing, like nobody’s watching, and as if, for once, she wouldn’t give a shit if they were.

The episode (and the series) ends with Lindsay saying goodbye to her family and Sam’s geeky friends as she boards a bus bound for the university’s “academic summit.” Sigh.

But then at a stop not far down the road, Lindsay disembarks that bus and climbs into a VW bus with her new Deadhead friends to begin was we hope is the long, strange, fascinating, adventurous, joy-filled trip that is her life.

Makes me think of a line from another Dead song: “Scarlet Begonias.”

“Once in a while you get shown the light in the strangest of places if you look at it right.”

I don’t have a specific memory of the first time I heard the Grateful Dead. For all I know, “Box of Rain” might have been my first song, too. I vaguely recall sometime late in high school asking a friend what band sang that song about Uncle John on the mixtape in her car stereo.

When she filled me in, I thought, “Huh. So that’s the Grateful Dead. Maybe I have heard them before and didn’t realize it.”

A year or so later, half-way through my freshman year of college in 1989, I went to my first Dead show near Chicago. I didn’t have a ticket (and didn’t care so much about the music, really) but wanted to see what all the fuss was about from a safe distance in the parking lot where the aromas and sights and sounds and colors and patterns and vibe of Deadhead central overwhelmed my senses.

I bought a silver bangle for $10 and almost 26 years later, it’s still there on my right wrist.

In my early 20s, I ended up seeing a number of Dead shows, including Jerry’s penultimate performance at Soldier Field on July 8, 1995. (I still haven’t quite forgiven myself for not going the next night. But when you’re 24 years old, you never expect any time to be the last time.)

The next night, July 9, 1995, the band performed “Box of Rain”during the final encore—the last song the Dead performed with Garcia—the pied piper of Deadheads worldwide, died exactly one month later.

As Garcia strummed his guitar, Lesh (on lead vocals) sang the closing lyrics: “Such a long, long time to be gone, and a short time to be there.”

Indeed.

What I didn’t know at the time was the story behind “Box of Rain.” That took me another quarter-century to learn (last week).

I’ll let Phil and lyricist Robert Hunter tell it.

How many times had I heard “Box of Rain” and simply thought, when I gave it much thought at all, that it had an interesting spiritual theme, particularly in the lines,

It’s just a box of rain

I don’t know who put it there

Believe it if you need it

or leave it if you dare

But it’s just a box of rain

To me it seemed like a wise caution against holding any belief too tightly. I had no idea it was written as both catharsis and salve for a dying man and the son who didn’t want to let him go.

Such a long, long time to be gone…

Hearing them with new understanding both of its backstory and of what the sorrow of losing a beloved father feels like—the cyclical, non-linear nature of the beast that is grief—brought tears to my eyes. I’ll never hear that song the same way again, and in turn, in some small way at least, knowing Lesh’s story allows me to understand the story of walking with my darling father through his last days in a new way. In that moment of recognition where sound and story meet, I found something I didn’t realize had been there all along, waiting for me to discover (and believe) it when I needed it.

Of course the sociological notion of a “third place” is predicated on an actual, physical space. Perhaps even a sacred space, of a kind. But what if we talk about sacred space the way Joseph Campbell did when he said: “Your sacred space is where you can find yourself again and again.”

That place is for me, and no doubt many generations of Deadheads to come, most reliably, in the music.

Look into any eyes

you find by you, you can see

clear through to another day

I know it’s been seen before

through other eyes on other days

while going home…