Operator said that’s priv’ledged information,

And it ain’t no business of mine.

It’s floodin’ down in Texas, poles are out in Utah,

Gotta find a private line.

~ “Operator”

In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell patented a device that could represent accurately the human voice. It thoroughly, irreversibly altered our interconnection, enabling us to talk to another person across an enormous distance with the sonic clarity of being in the same room.

A special series on religion and culture produced in collaboration with the Office of Religious Life at the University of Southern California

Though initially only accessible to the very wealthy, the telephone soon proliferated, and with it, a promise of relational immediacy—no longer did a person need to wait days or weeks to communicate by exchange of letter or telegram.

The telephone promised a pathway out of our isolation and loneliness. In 1926, Arthur Pound sung its praises:

“We who are still young have beheld millions of farm families emerge from isolation, the tucked away mountain hamlet and prairie village brought into touch with the busy currents of trade and social intercourse. Many new tools and systems originated by science and organized by business have contributed to this result; but the telephone has done as much as any other factor to make America strong and united; and, what is even more important, to make America aware of her strength and unity.”

The telephone’s near-mythical power (and promise) to connect, network, and unify us has expanded exponentially with each new technology that has succeeded it, each portending to possess ever greater ability to be in contact and connected.

Take Facebook’s succinct mission statement, for example, which nearly 80 years later echoes Pound’s sentiments:

“Founded in 2004, Facebook’s mission is to give people the power to share and make the world more open and connected. People use Facebook to stay connected with friends and family, to discover what’s going on in the world, and to share and express what matters to them.”

Certainly technology has networked us in incredible, albeit sometimes creepy, ways. As a prolific Facebook user, I often am taken aback by running into old friends, acquaintances, or teachers who casually ask about my work, education, or wedding with uncanny familiarity given our distance in physical space and time.

I sang in a new church recently where the pastor realized she knew my name from somewhere.

“Are you friends with the Hackett family on Facebook?” she asked.

“Yes,” I replied.

That’s how she knew me. Virtually. Through pixels on a screen and shared aquaintances.

Like Pound, I sometimes find it effervescently exciting, all this connection. I’m thoroughly guilty both of offering too much fodder for this glut of interconnection and for feasting on its excesses.

But it begs the question: just how connected does all this technology actually keep us?

My generation—the dreaded millennials —seems to move more than any previous generation. Like many of my peers, I left my hometown at age 18. Though I guess I always intended to return, I’ve moved ever farther away from my source, spending years in Washington, California, Arizona. I also spent weeks or months back home in Montana, or abroad, or on the road.

This mobile life, especially when linked to that naive adolescent vulnerability and curiosity, put me in touch with a great many complicated, marvelous people (for they are the best sort):

- The punk musician and anarchist whose father was dying of a late-diagnosed terminal illness.

- The 20-year-old who lived in his VW van in Montana, homeless after foster care failed him and a grave illness left him broke, who read physics textbooks and Derrida for fun.

- The college graduate/tree-feller/agriculturalist who lived in a co-op house closet under the stairs, like Harry Potter.

And so many others.

For a few years in my early-to-mid-20s, I lived vividly amongst these eclectic, eccentric souls, each for his or her own brief but glorious chapter of our lives. We forged our connections around a table, playing games of Scrabble and cards, or listening to mix CDs, or spending nights under a canopy of stars.

Transcendence came in conversations that lasted for hours—sometimes days— and meandered through our sophomoric musings on philosophy, religion, hopes for a future well-lived.

The spell broke when I initiated the first real chapter of my “adult life” in Seattle, a city known for its quirkiness, but also for its social chill. Bit by bit, as I became invested in graduate school and settled into my craftsman studio apartment with wood floors and a lovely claw-foot tub, I lost touch with the people who had set my life so wonderfully aflame.

It happened slowly at first, but then with breathtaking acceleration tempered only by the emptiness that replaced it.

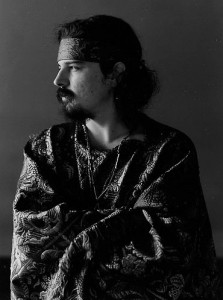

The Grateful Dead’s Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, who wrote “Operator,” and died in 1973 at the age of 27. Photo by Herb Greene from the UCSC Grateful Dead Archive. Used with the kind permission of the photographer.

In his song “Operator” from American Beauty, The Grateful Dead’s Ron “Pigpen” McKernan wrote about this kind of flailing, discombobulating loss that often welcomes us when we cross the threshold from adolescence to young adulthood. Pigpen’s “rider” has departed for an unknown place. He’s lost her number and can’t find it.

“Directory don’t have it, central done forgot it.” And he’s desperate to reach her, if for nothing more to make sure she’s “doing it right.”

It’s clear in the song that Pigpen’s search for a viable number is, at best, a futile proposition. Still he dials the telephone operator to try find that lost landline. Problem is, he’s not even sure which direction she went.

“I think she’s somewhere down south, down about Baton Rouge,” Pigpen begins, but then changes his mind. “She could be hangin’ round the steel mill, working in a house of blue lights, riding a getaway bus out of Portland.”

The song came out in 1970 when Pigpen was 24. Though we’re a generation apart in our age and technologies, I feel a kinship with him in these weary, floundering moments.

Lately I’ve noticed that many of the people I’ve known best face-to-face seem awfully hard to find. Our connection, once burning with possibility and joy, began to cool, as cell phone calls dwindled and numbers eventually changed or were disconnected. As our shared realities drifted apart in their likeness, like Pigpen, I also turned to technologies that promised connection to try to tamp down the yearning and temper that sense of loss.

Where Pigpen called up the trusty telephone operator, I did my pining alone, with only the camaraderie of a search engine. Given the daily overdose of notifications and messages and targeted ads, I thought (subconsciously) surely Google and Facebook should know how to reconnect us. When a pang of dislocation hit me, I aimed to satisfy it—to run down a line, as Pigpen might have put it—by combing web pages exhaustively, or by typing in a variations of a name a hundred different ways until I found some detail, some evidence that my dear ones were still out there, abiding.

On a good day, a bid for re-connection would arrive. An e-mail reply. A notification. A “like.”

Give me another.

Refresh. Refresh. Refresh. Refresh.

It turns out, Pigpen and I aren’t alone. In fact, we’re part of a growing legion of folks who feel disconnected, and turn to our technologies to slake our thirst for community, only to be met with empty promises of connection. A few years back, The Atlantic reported on this whole social media connection conundrum, declaring loneliness a rising affliction.

And earlier this year, the BBC’s Rebecca Harris cited a variety of studies that showed that such loneliness is, in fact, the product of these modern cyber or virtual societies crafted to connect us.

According to Harris,

“We live in nuclear family units, often living large distances away from our extended family and friends, and our growing reliance on social technology rather than face to face interaction is thought to be making us feel more isolated. It means we feel less connected to others and our relationships are becoming more superficial and less rewarding.”

This loneliness is even being labeled a health risk.

The way out of all this quagmire of disconnection is complicated and individual. I managed to turn it around by realizing that moments under stars and engrossed in the company of others who were physically present were critical to my well-being. I moved out of my perfect studio apartment and into a ratty house in a hip neighborhood, surrounded by a legion of housemates. I met a man who set my life ablaze again, this time with shared passions, a wry humor with a silly streak, and a proclivity toward community.

I put away my phone in order to devote free time to art, music, and curating opportunities for togetherness. I turned to studying music and religion as a graduate student, keenly aware of the powerful ability of both to link us and give us identity.

I put those who had passed through my life on their own shelf, held tenderly in my memory, thankful for the growth, the joy, the awakening. When I find myself lingering nostalgically, I call upon Pigpen, who knew how to let go:

“I don’t know where she’s going,

I don’t know where she’s been,

long as she’s doin’ it right.”

May we all be so wise, ever moving forward, and finding bids for true connection along the way.