The “shot heard around the world” ignited the American Revolution and led to the independence we celebrate every July 4th. Before that shot, a preacher delivered a prayer. That prayer is celebrated in paintings and even in our law. The Supreme Court uses this prayer today to interpret the meaning of the Constitution—a Constitution that wouldn’t become the law of this new land for another 15 years.

Supreme Court justices have cited this preacher and his prayer to justify congressional chaplains, prayers before legislative sessions, and even a 40-foot-tall Christian cross on government land. That jurisprudential logic is flawed, but unsurprisingly, so is the history.

As with much American mythology, we’ve only heard part of the story. We’re told of the chaplain and his prayer—but not of his treason.

* * *

“Nothing is more dreaded than the national government meddling with religion,” mused John Adams, reflecting on his failed 1800 re-election bid. As president, he mixed church and state, a mistake he ultimately blamed for his electoral loss. Adams had called for a national fast, a governmental overreach which he believed “turned me out of office.” But when the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia in 1774, Adams lacked the benefit of this hindsight. Without it, he and the other delegates appointed a chaplain, Jacob Duché (“Dushay they pronounce it,” wrote Adams), to say a prayer. The story of Duché’s appointment and prayer come down to us from one of John Adams’ many letters to his wife, Abigail.

From John Adams’ letter to his wife, Abigail.

“When the Congress first met, Mr. Cushing made a Motion, that it should be opened with Prayer,” begins Adams’s story. Much like Adams’ electoral loss after meddling in religion, Thomas Cushing was ousted from the Congress the following year—though more likely for his opposition to the colonies declaring independence.

Cushing’s prayer motion, wrote Adams:

“was opposed by Mr. Jay of N. York and Mr. Rutledge of South Carolina, because we were so divided in religious Sentiments, some Episcopalians, some Quakers, some Aanabaptists, some Presbyterians and some Congregationalists, so that We could not join in the same Act of Worship.”

John Jay and John Rutledge, who would become the first and second chief justices of the Supreme Court, opposed the prayer because the Continental Congress was religiously diverse—and the more diverse a company, the greater the division religion sows. It’s best to remove religion from the political equation. Our framers eventually enshrined that idea in the Constitution.

Then comes the part of the story we see most often: “[Sam] Adams arose and said he was no Bigot, and could hear a Prayer from a Gentleman of Piety and Virtue, who was at the same Time a Friend to his Country.” The motion passed.

Now, when we hear that story today, it’s often used to suggest that people who oppose elected officials abusing government power to impose their religion on others are the “bigots” that Sam Adams disclaimed. That ignores the fact that this was still a British colony with an established church and that the U.S. Constitution wouldn’t invent the separation of church and state for another 15 years or so.

But there’s another dimension to the story: The prayer motion was born of political, not religious, considerations. The delegates had carefully selected Duché in order to influence a large sect that was relatively unsupportive of American independence.

Duché was an ordained Episcopal clergyman who presided over a loyalist congregation but was willing to affiliate with the soon-to-be rebels. Sam Adams only approved of Duché because he “had heard that Mr. Duché” was a “Friend to his Country,” despite being part of King George III’s church.

In other words, this prayer proposal wasn’t about religion or about the delegates joining hands for worship. This was realpolitik. It was strategic piety. John Adams recorded in his diary the observation of another delegate which admits as much, “We never were guilty of a more masterly stroke of policy, than in moving that Mr. Duché might read prayers.” Policy, not piety.

For those who wish to portray the United States as a Christian nation, the story ends with Duché’s prayer and never grasps that this was a political stunt. But this is when things just start getting juicy.

The British captured Philadelphia in 1777 and Duché spent one night in jail before turning coat and forsaking America. “Mr. Duché I am sorry to inform you has turned out an apostate and a traitor. Poor man! I pity his weakness, and detest his wickedness,” wrote John Adams to Abigail.

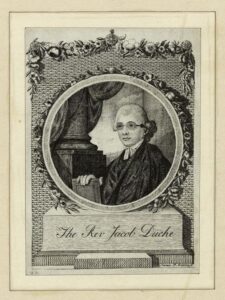

The Rev. Jacob Duché

Duché condemned American independence, the Continental Congress, and the soldiers fighting for independence in a letter to George Washington. Duché assured Washington that his political apostasy was genuine, he was not coerced by the British and that the letter expressed “the real sentiments of my own heart, such as I have long held.” Duché explained that he had only agreed to be chaplain for the Continental Congress out of self-interest, to “procure some favourable terms” for his position and church.

In effect, Duché was saying that he used his religion for political ends, just as the Congress was using him. When our founders later chose to separate state and church, they did so in part because “religion and government will both exist in greater purity, the less they are mixed together,” as James Madison explained. This prayer may be a fine example of that failing.

In his letter to Washington, Duché called on the Continental Congress to rescind “the hasty and ill-advised declaration of Independency,” likening independence to idol worship, before vilifying Congress as a group of “illiberal and violent men.” Duché next turned his pen on the army, “a set of undisciplined men and officers, many of them have been taken from the lowest of the people, without principle, without courage . . .”

The Rev. Jacob Duché was a traitor.

On the same day that Duché penned this quisling letter, General Benedict Arnold was trouncing British General John Burgoyne at Saratoga. Arnold’s later treachery lives on in infamy, but Duché’s is forgotten. Or perhaps Duché’s treachery is ignored so that his prayer can be venerated? So that Christian nationalists can point to a long history of government prayer to justify today’s violations of America’s original contribution to political science: the separation of state and church.

Whatever the reason, federal judges repeat the religion and ignore the treason when they use Duché’s prayer to interpret our Constitution.

Justice Alito used the Duché story to uphold a 40-foot concrete cross on government land maintained with hundreds of thousands of taxpayer dollars. Alito spent a paragraph on the election of Duché as chaplain without mentioning his name or his perfidy:

“…Thus, when an Episcopal clergyman was nominated as chaplain, some Congregationalist Members of Congress objected due to the ‘diversity of religious sentiments represented in Congress.’ … Nevertheless, Samuel Adams, a staunch Congregationalist, spoke in favor of the motion: ‘I am no bigot. I can hear a prayer from a man of piety and virtue, who is at the same time a friend of his country.’ … Others agreed and the chaplain was appointed.”

The Supreme Court did the same thing in 1983 to uphold Christian prayers before legislative sessions. The six justice majority used Duché’s prayer as a cornerstone to develop that narrative, writing that “the Continental Congress . . . adopted the traditional procedure of opening its sessions with a prayer offered by a paid chaplain.”

That decision marked a shift in the high court’s jurisprudence. It was one of the first times the court elevated “history and tradition” over legal principle and the Constitution. The underlying legal question was so simple that the dissenting justices had “no doubt that, if any group of law students were asked to apply the principles of [the Constitution] to the question of legislative prayer, they would nearly unanimously find the practice to be unconstitutional.”

Now, venerating history and tradition over legal principle and the Constitution is a common tactic of the ultra-conservative bloc of justices who control the court. They do the same thing for all the right-wing fetishes—guns, abortion, and the privileging of Christianity. The end result of which is obvious. We’ll be dragged back to a time when conservative White Christian men ruled. When they ruled over women. When they ruled with violence.

The history itself is never fully told. But even if it were, this “history and tradition” legal argument makes little sense.

The Constitutional Convention (1787) took place thirteen years after Duché prayed (1774) and the delegates at that convention rejected a prayer that was proposed halfway through the proceedings. Everyone “except for three or four persons, thought prayers unnecessary,” according to Ben Franklin. It’s no coincidence that these proceedings, unlike the Continental Congress at which Duché prayed, were secret. To have any political value, strategic piety must be public. In private, when drafting the Constitution, our founders had no need of prayer.

But there’s something even more striking about that timeline. Duché prayed in 1774, the prayerless Constitutional Convention met in 1787, and the constitution was ratified two years later, in 1789. When Duché prayed there was no United States of America, the colonies hadn’t even declared independence. There was no godless Constitution drawing its power from We the People, rather than a deity. The First Amendment to that Constitution wasn’t ratified for two more years (1791). In short, there was no constitutional separation between state and church. But judges and justices, whose sole job is to interpret and apply the U.S. Constitution regularly use a prayer from a decade and a half before the document existed… to interpret that document.

Courts that have upheld prayers at government meetings do so by elevating history over legal principle. And it’s not even accurate history—it’s incomplete, half-forgotten or even suppressed. Duché betrayed American independence. When we hear these unconstitutional legislative prayers before government bodies all over this country we should remember their legacy is one of treason and betrayal. They are, at heart, un-American.

Happy Fourth of July, America.

This article is adapted from The Founding Myth: Why Christian Nationalism is Un-American which examines and debunks the historical disinformation that forms the basis of the Christian nationalist identity in the United States.