“Comfort me.”

“COMFORT ME.”

“COMFORT ME! COMFORT ME!! COMFORT ME!!!”

Bono is standing at the edge of the stage that runs the length of The Forum arena in Inglewood, Calif., howling that word—comfort—at the top of his lungs before a crowd of 17,000.

The 55-year-old rock star is shouting—at God, to God—a prayer that has become an all-too familiar litany of the brokenhearted for the U2 family in recent months. Fewer than 24 hours earlier, in the wee hours of May 27, the band’s longtime tour manager and a fixture in the U2 community, Dennis Sheehan, died of an apparent heart attack in his Los Angeles hotel room.

Not just any band could take their fans by the hands and say, essentially, please walk with us through the valley of the shadow of death. We’re one, but we’re not the same; we get to carry each other …

But since its inception in 1976, the band formed by four teenage boys from Dublin’s hardscrabble north side has opened a vein, sharing their most vulnerable moments and struggles with anyone who would listen.

And sorrow has visited the U2 family far too often this season.

Bono narrowly escaped a bicycling accident in New York’s Central Park last November with his life (thank God for helmets) and may never play guitar again because of the damage done to his left arm during the crash. It was a hard-won physical rehabilitation that got the lead singer ready to return to the stage for the launch of the “Innocence + Experience” tour in Canada on May 14. Then, just a few days before the tour began, drummer Larry Mullen’s father passed away at the age of 92. Mullen played that first concert in Vancouver after laying his father to rest just one day earlier in Dublin.

And in late February, U2 lost the man the band called its “North Star,” the Rev. Jack Heaslip, an Anglican priest who had known the band’s members since they were in high school (he was a guidance counselor at their Mount Temple school), and who, for 20 years had traveled the world with them as “spiritual counselor” and chaplain to the small city of technical, artistic, and support crew that tours with the band for months (and sometimes years) at a stretch.

The Rev. Heaslip, known simply as “Father Jack,” was a subtle if stalwart omnipresence. He was known to walk the perimeter of each performance venue, praying for the band, yes, and their crew, but also for the people—the fans—who would arrive by the thousands to hear U2 perform. Like Dennis Sheehan, “Father Jack,” kept everything running, behind the scenes—in the realm of the Spirit. His passing was a knee-bending blow.

“The extended family is very important to us, and we look after each other,” Bono told the audience the evening of Mr. Sheehan’s death in Los Angeles. “A lot of U2 songs over the years have been written to fill a void, an absence, a hole in the heart left by a loved one,” Bono continued, before launching into “Iris,” a heart wrenchingly personal song about the mother he lost when he was just 14 years old. “This next one is one of those. It’s for my mother, Iris, who taught me that through the wound, that this kind of thing can be, there’s an opening to something fantastic.”

Bono, guitarist The Edge, drummer Larry Mullen, Jr. (who, like Bono, also lost his mother at a young age), and bassist Adam Clayton grew up together, found life partners, reared children, forging bonds of sacred friendship and creative collaboration that are rare anywhere—and likely unique in the annals of rock’n’roll.

Many of the people involved in helping the four band members make music have been with them for decades. Theirs is a fiercely loyal tribe. Once you’re in, you’re in, a bit like salvation by grace, I suppose.

Waves of Regret, Waves of Joy

Anyone who has listened even casually to U2 knows that the spiritual world is the band’s wheelhouse. I’ve been a fan since the age of 12—I experienced my first epiphany while listening to the band’s song “Gloria” for the first time in 1983. I first became acquainted with the band after traveling (as a religion columnist) with Bono in 2002 on his humanitarian bus trip (DATA’s “Heart of America” tour) across the American Midwest urging evangelical Christians (and others) to respond to the then-pandemic of AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa.

We’ve had many conversations, publicly and privately, over the years about our shared Christian faith.

From their earliest days as a band, U2 has sung about wrestling with angels, the magnificent and mystical, God the Father, the Divine Feminine (who moves in mysterious ways). They’ve confessed their sins, aired their doubts, celebrated amazing grace, and mourned their losses. The band (and its effervescent lead singer, Bono, in particular) often wears its spiritual predilections on its sleeve and they’ve received more than their share of criticism over the years because of it from all sides who’ve accused them of being too rock ‘n’ roll to be true believers; or too Jesus-y to be real rock ‘n’ rollers, or both.

And yet the loyalty and love U2’s members have for each other and their extended tribe is mirrored often by their fans. Whether they believe the last good album the band made was long before 1991’s sonic game-changer Achtung Baby or that everything the four lads from Dublin create together is a work of art, U2’s fans have stuck with them.

The band’s lyrics, often laced with biblical language and imagery, were so influential on a certain slice of the Christian community that a liturgy called the “u2charist,” which incorporates U2’s music into ecclesial worship services across traditions, gained popularity in the early 2000s.

There’s a relationship between an artist and his or her audience, surely, but sometimes, that relationship is more than entertainer-meets-entertained, or a producer-consumer transaction. Sometimes, particularly when artist and audience are in the same physical space, something transcendent takes place.

Such is the case, I would argue, when U2 is on tour, playing (and praying) live with and for their fans. Whatever it is that transpires in those live moments surpasses the kinesthetic, energetic exchange between bodies in a room where music is being performed by musicians on actual instruments.

There is a real sense of metaphysical maneuvering amidst the crowd when, as each of U2’s members have described it on various occasions, “the Spirit is in the room.”

“Have you ever been experienced?”

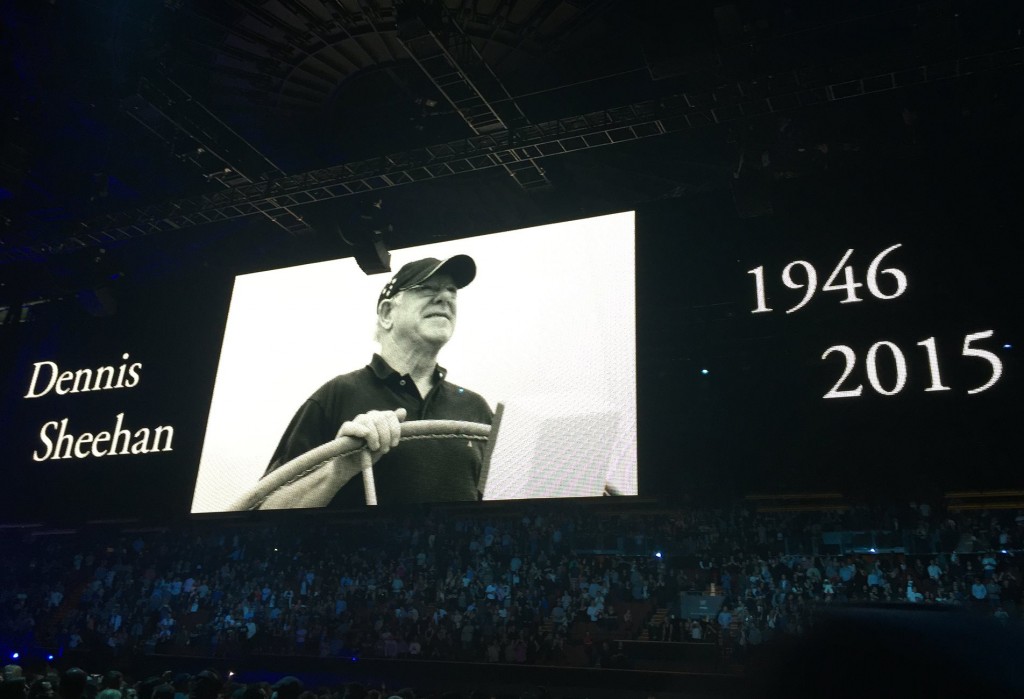

A tribute to U2’s longtime tour manager, Dennis Sheehan, who had died earlier in the day appears at the end of the band’s concert at The Forum arena in Los Angeles on May 27. Photo by Cathleen Falsani for Religion Dispatches.

After attending a U2 show in San Jose, Calif., earlier this month, Noel Gallagher of the band Oasis described it as a “psychedelic experience” that was “staggering.”

“It starts off as a punk rock gig but then it gets intimate, there’s a lot of truth in it about where they come from and the people that they are,” the notoriously prickly Gallagher said. “At points it’s quite touching when you see footage of people like Bono’s mum and his kids, stuff like that, walking up the street they grew up on.”

In 1967, Jimi Hendrix, one of the icons of pop culture’s psychedelic movement, asked the world, “are you experienced?” The search for such an authentic experience is essentially a spiritual one—a quest for an authentic experience with the divine, transcendent, that which lies beyond this physical realm.

Authenticity is one of the most deeply felt needs of our time, particularly among Gen X and Millennials. Authenticity, as Robert W. Terry, the late director of the Reflective Leadership Center at the Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota, described it, is:

“ubiquitous, calling us to be true to ourselves and true to the world, real in ourselves and real in the world, When authenticity is acknowledged, we admit our foibles, mistakes and protected secrets, the parts of ourselves and society that are fearful and hide in the shadows of existence.”

The “Innocence + Experience” tour, now in its third week, hums with authenticity. U2’s two-hour performances in venues no larger than 20,000 seats manage to feel at once intimate and expansive. The audience is invited into U2’s deeply personal, spiritual history—growing up amidst sectarian violence in 1970s Ireland where religion was as divisive as dynamite, the loss they suffered as a people and as children, the fear and longing, confusion and defiance that such a milieu fostered.

The band literally climbs into their past via a gargantuan state-of-the-art multimedia screen they call “the divide” that runs the length of the stadium along the narrow center stage that allows fans to get physically close to the musicians. They play inside the screen as images from their past—including drawings of Bono’s childhood home on Cedarwood Road in Dublin and home movies of his mother—are projected on the surface.

It’s difficult to describe—you have to experience it firsthand to grasp it fully—but suffice to say the band is bringing their fans into the music in ways I’ve never seen.

Car bombs explode and hundreds of pages from Dante’s Inferno, Alice in Wonderland, and Eugene Peterson’s para-translation of the Bible, The Message, drop from the rafters. I caught a page with a passage from Psalm 89, which read in part,

“Your love, God, is my song, and I’ll sing it!

I’m forever telling everyone how faithful you are.

I’ll never quit telling the story of your love—

how you built the cosmos

and guaranteed everything in it.“

A few verses later in the same Psalm, the author, King David, rails against the Almighty whom he says has abandoned him, leaving him “an impotent, ruined husk…How long do we put up with this, God?”

“How long to sing this song?”

I’ve seen U2 play live a couple dozen times in the last 15 years or so and more and more I find myself watching the crowd almost as much as the band. The show that followed Dennis Sheehan’s death was a particularly raw, powerful experience. Bono invited the crowd to lift people up (presumably to God) who need lifting, those of us who are mourning, broken, maybe more than a little bit lost. He urged the crowd to “let it go”—whatever “it” might be. He wasn’t preaching, exactly. It was more collaborative than that, giving the audience the space and freedom, perhaps, to “speak what we feel, not what we ought to say,” to borrow a line from King Lear that might have been written by the Psalmist himself.

The band played one of their spiritual anthems, “Bad,” with its call and response:

If I could, through myself, set your spirit free

I’d lead your heart away, see you break, break away

Into the light and to the day.To let it go and so to find away.

To let it go and so find away.

I’m wide awake.

I’m wide awake, wide awake.

I’m not sleeping.

U2’s encore that night was a tribute to Mr. Sheehan, a display of photos and video of their lost captain on the huge screens he helped imagine and create. The Forum morphed into a vast Irish wake as the band performed “40,” their perennial closer, for the first time on this tour.

Bono told the story of an early live performance of the song, drawn from the words of Psalm 40 itself, at Colorado’s Red Rocks amphitheater many years ago. That night Mr. Sheehan had tried to get the audience to join in on the refrain, “How long to sing this song?” by singing it into a mic himself—one, pure, solo tenor shouting into the void.

On this night more than 25 years later, wide awake, drenched in grief and grace, the audience robustly obliged, repeatedly echoing Mr. Sheehan’s refrain, How long to sing this song? as the band members exited the stage one by one—even as the show drew to its official close and the house lights came up.

As we slowly emerged into the harsh lights of the Forum parking lot, a man nearby expressed what many of us were feeling: “That was better than church.”