Many contemporary painters and photographers take childhood as their subject, though few do so with the ghoulish stare of Marlene Dumas, whose first major American exhibition, “Measuring Your Own Grave,” is currently on display at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Death drapes Dumas’ signature portraits: the head of a dead Marilyn Monroe, dead apartheid-era Afrikaners, dead Jesus, and dead faceless bodies—even the live subjects seem fatally wounded. Her canvases don’t show violent acts as much as they show how we are after being violated; the way the face bears decimation long after the terror is past. “The Painter” (1994) observes a standing toddler, nude, hands dipped in blue and red paint. Or is it blue paint and red blood? It doesn’t matter, really, since the painter’s face bears a clocked stillness that suggests she’s already seen too much. Innocence is impossible in Marlene Dumas’ world.

Will Dumas someday soon turn to Jett Travolta? If she does, how will she frame him? Would he be grabbing Kelly Preston’s face, suggesting untoward mother-son intimacy? Most likely Dumas will  skip the sentiment and stare instead at 16-year-old Jett lying on the bathroom floor of his family’s Old Bahama Bay condo, where he was found Friday morning by his nanny, Jeff Kathrein. This is where her gaze would linger, forcing the viewer to think about youth, about flesh, about need, and about rigor mortis.

skip the sentiment and stare instead at 16-year-old Jett lying on the bathroom floor of his family’s Old Bahama Bay condo, where he was found Friday morning by his nanny, Jeff Kathrein. This is where her gaze would linger, forcing the viewer to think about youth, about flesh, about need, and about rigor mortis.

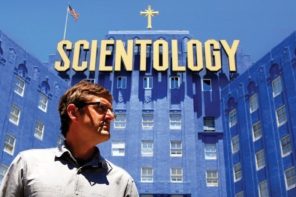

Before we get Dumas’ rendition, we’ll have to settle for the glaring inelegance of tabloid portraiture. If you don’t yet know the religious turn this will take—it has taken—just wait for it. Watch and stare, gape-mouthed, as Jett’s death is blamed not on malady, but on the tentacular reach of Mr. Mysterioso, L. Ron Hubbard. Watch the parade of medical experts, legal consultants, and members of the Autism Police parade their aghast faces across whatever media outlet will tolerate their hack. Watch the competitive forms of parental hysteria, as cleaning products, mood stabilizers, and engrams are tossed about as inciting accomplices to the crime. Watch too how Scientology is confused with Christian Science, and how legal rights are compromised, constantly, to make everyone else feel better about just how scary it is to watch a child grow, and to worry that (s)he won’t.

Consuming celebrity culture is always about inadequacies, and consuming this sad scene is no different. It’s tempting to rehearse the details of this consumption, to work through the crime scene and the motive, to share what we know about Jett’s medical records, his ambulance ride, and his parents’ abiding love for their church. It is tempting to do so because it is what we do, studying minor melodramas to fill conversation at check-out lines, to fill the spaces of our own losses as we stare, superior, at the failures of others. But to rehearse the details is to endorse the rehearsal of details, to plug by proxy that it is reasonable to want to know a father’s last words, a family’s religious decisions, or a teenager’s chemical balance. As if it is reasonable to know that which should make us, somewhere inside, wince to know.

Nonetheless, we will know and prosecute, know and defame, know and titter. We will know the Travolta-Preston world soon better than we know Gaza, better than we know western Xinjiang, and better than we know Detroit. For some of us, more than we want to admit, we will seek to understand Jett and his suffering better than we do our own child’s. We will think—from our helicopter parenting and minivan mindfulness—that we are doing better by our children because we pay attention without L. Ron or because we drop by the doctor at every sniffle. We will think this. You will think this.

Before it begins (the inquests, the circling paparazzi, weeping Kelly explicating before weeping Oprah) let us pause, briefly, to think about that body, to think about his floor, and to think about that thing that is much harder to make spectacular, to make sensational or cultish. The tedious work of parenting is beyond unsexy. It is boring and disappointing, repetitive at best and adventurous at worst. And to make a world feel better for what a lousy job they do at it (or how lousy they think they’re doing at it), they will spend some time parsing the possibly religious structures of two actors’ struggles with it. The structures of religion allow for that, and will survive beyond that, furnishing a bendable whipping post for human frailty.

Scientology cannot be killed by the lambasting of its adherents, no matter how many of its antagonists would like their defamation to genuinely deconstruct. So as we enter a new year, a new presidency, and a new set of childbirths, we may want to turn a bit from the crumbling content of others. Better effort might be put toward a pilgrimage to paintings that remind us, with excruciating acuity, that whatever we make at our kitchen tables, in our bedrooms, and at our play groups, it is nothing over which we possess any real control.