There’s an explosion on nearly every other page of George W. Bush’s Portraits of Courage: A Commander in Chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors. Mortar attacks. IEDs. Suicide bombs strapped to children. Bush wrote short essays to accompany each of his 98 paintings of veterans, and I read them in a single sitting. The cumulative effect of war’s broken bodies was overwhelming—bodies missing arms and legs and parts of tongues, burned bodies, bodies with skull fractures and amputated feet and broken backs and broken necks and bullets lodged between vertebrae; bodies with migraines and double vision and lost hearing and missing eyes.

The essays share a similar arc: the subjects enlist, serve multiple tours in Iraq or Afghanistan, are horrifically injured, struggle in the aftermath of war, and then find meaning and purpose. Spouses, golf, mountain bikes, children, and God all play roles helping Bush’s wounded warriors heal and recover. But Portraits of Courage doesn’t present a sanitized version of war. Yes, it trades in expected patriotic narratives of sacrifice and triumph, but it also reveals the fight to survive after trauma and violence, to live with post-traumatic stress and traumatic brain injuries, to return to daily life with an altered body and mind in a country with very few visible signs we’re still at war. This is not a new or unusual storyline to find in books about war.

But what makes Bush’s book different, what makes his paintings impossible to stop thinking about, is that the artist who created these images is the very person who started the wars that continue to reverberate in the lives and bodies of the people he paints.

In Laura Bush’s foreword she describes George, who she never thought would become an artist, seeing a painting by Thomas Moran in a book and noting there had been a Moran painting hanging outside the Treaty Room at the White House. “George had passed that painting nearly every night . . . but he never noticed it,” she writes. “His attention was elsewhere. Our country had been attacked, and as a wartime President, he received casualty reports every day from the front lines. His thoughts were with the troops on the battlefield, the families of the fallen, and the wounded warriors in hospitals around the world. Art was the last thing on my husband’s mind.”

Bush now spends several hours a day painting. In his opening essay “Painting as a Passion,” Bush recalls telling one of his art teachers, “[T]here’s a Rembrandt trapped in this body . . . Your job is to liberate him.” He first painted a cube, then a watermelon, then an apple. He took online courses from the Museum of Modern Art to study art history. He painted his pets and landscapes at his ranch and self-portraits in his bathtub and shower. He painted world leaders. “Before long I started to see the world differently,” Bush writes.

Another teacher suggested Bush paint people he knew who others didn’t, so he decided to paint the wounded warriors he’d met during mountain-bike rides and golf tournaments sponsored by the Bush Institute. Alone in his studio, Bush painted their portraits from photographs. He writes, “As I painted them, I thought about their backgrounds, their time in the military, and the issues they dealt with as a result of combat—many from visible injuries, others from invisible wounds.” He continues, “I intend to salute and support them for the rest of my life.”

Bush’s close-cropped portraits are less Rembrandt and more Van Gogh—thick paint, vibrant pigment, visible brushstrokes, swirls of color in the background. Many portray the veterans’ prosthetic legs and arms. The portrait of Staff Sergeant Timothy Brown (United States Marine Corps, 2003-2014) shows Brown seated, his left arm holding his right arm, dark and mechanical. During his third combat deployment, Brown stepped on an IED, a thirteen-pound blast that severed both legs above the knee and his right arm above the elbow. Brown underwent 40 surgeries and spent three and a half years at Walter Reed.

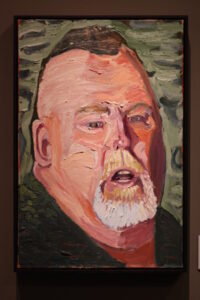

Painting of Scott Alan Adams Sr. courtesy of George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum.

Military green dominates the portrait of Sergeant First Class Scott Alan Adams Sr., who served in the United States Army from 1986 to 2008—green background, green eyes, green shirt, green in his hair and eyebrows. Bush’s essay tells how, in January of 2007, during Adams’ fifth deployment, his vehicle hit two landmines laced with white phosphorous, a chemical compound that causes terrible burns. Adams was knocked unconscious and then came to trapped in his vehicle, engulfed in flames. Bush explains that Adams still suffers from traumatic stress, how he can’t ride in a car in the far-right lane because he’s afraid of IEDs, and his unease is palpable in the portrait. Adams’ mouth is slightly open, his eyes vacant. Heavy strokes of pink and rose and peach form his face, one side purple and in shadow.

When I read this book, I like Bush. I soften toward him. Maybe it’s the contrast with our current president, whose policies wake me in the middle of the night, in a sweat, afraid of nuclear war and white nationalists. Or maybe it’s because I’m generally fond of artists; painters, sculptors, ceramicists, animators—these are my people. Bush’s stories give me the feeling that he’s a good guy. He knows the soldiers he paints. He visits them in the hospital, knows their kids, invites them to his ranch, gives them nicknames, rides bikes and plays golf and even dances with them.

But this affection works like a kind of erasure. Portraits of Courage does make American veterans visible—their wounds, struggles, contributions, resilience—but it also renders most of the Bush presidency invisible: the lies that started the wars, the deception, the destruction, the torture. While reading this book, it takes great effort for me to keep at the front of my mind the awareness that the soldiers’ bodies bear the consequences of Bush’s wars, while his reveals no sign of struggle, no consequence.

Bush’s portraits of veterans remind me of another set of portraits. The American lawyer Susan Burke, accompanied by a writer, a playwright, and a painter, traveled to Istanbul in 2006 to take depositions from Iraqis who had been detained and tortured by Americans in Abu Ghraib prison. The painter, Daniel Heyman, made watercolor portraits of the former detainees while they described what had been done to them.

Like Bush’s portraits, Heyman’s works on paper are close-ups of faces accompanied by words. While Bush’s essays are separate from his paintings, Heyman wraps his subjects in their own words about the torture they survived. His painting “Every Night Graner Mistreated Us,” is accompanied by the following in black and blue paint: “One night they put blankets over the cell bars—this was the night the prisoner was killed—I was made to stand all night facing the cloth. I am hearing I thought a prisoner being forced to drink from a toilette like drowning. I could not breathe—I thought my time is near. Then the prisoner’s noise stopped.”

A painting titled “I am Ready,” includes these words: “One night they brought in a detainee, tied up. They called to me, ‘Do you know this man?’ And they pushed up his head, and he was my brother. They said if I did not cooperate they would bring my mother. They beat my brother in front of me. My elder brother. One day I saw . . . the prisoner right across from me—tied upside down, hanging from his feet.”

What if, in addition to painting wounded Americans, Bush had painted wounded Iraqis? Several years ago, when it first became known that the former President had started painting, the satirical news site The Onion ran a story titled, “George W. Bush Debuts New Paintings Of Dogs, Friends, Ghost Of Iraqi Child That Follows Him Everywhere.” In the background of every painting of pets and kitchen tables and couches was a dead Iraqi child.

Painting of Sergeant Matthew Zbiec courtesy of George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum.

Toward the end of Portraits of Courage, I thought I saw such a ghost. The third to last painting is of Sergeant Matthew Zbiec, whose face is positioned in the bottom half of the canvas, much lower than Bush’s other portraits. Behind him is a blue-grey triangular shape that stretches to the top of the painting. At first I thought it was the outline of the “hooded man,” the iconic photograph of the man standing on the box in Abu Ghraib prison, wires attached to his body, a blanket over his torso, a hood over his head.

When I was teaching at a university in California, I had a student, a veteran, who’d been stationed at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. He, too, is a painter and creates luminous images of the detainees he once guarded: hands holding a Koran; a line of men waiting in front of portable toilets; a boy in a yellow jumpsuit. When I asked him why he paints what he paints, he said, “Maybe it was my way of telling someone. I try to hide it.”

What if every president were forced to paint the bodies most harmed by their policies? For that matter, what if all of us were?

In John Berger’s The Shape of a Pocket, there’s a strange little essay called “Fayum Portraits” about images painted thousands of years ago in beeswax and pigment on wood or linen in a town called Fayum, south of Cairo. They were painted while the subject was alive, but when he or she died, the image was attached to the mummy and buried. Many of these paintings have been unearthed, and you can view them, in museums or online. Berger insists that because they were made in preparation for death, the Fayum portraits contain a greater urgency than other images, an urgency heightened in this time of displacement and emigration. “They gaze on us,” Berger writes, “like the missing of our own century.”

At the end of her foreword to Portraits of Courage, Laura Bush writes, “I am grateful that, at last, George has a chance to develop his artistic eye.” Tell me, please, Mr. President, what is it that you can now see?