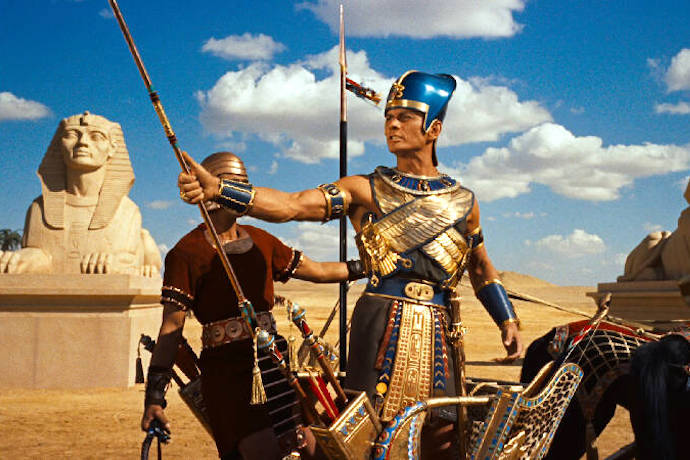

As Passover approaches this weekend I often reminisce about how, as a young child, the highlight of my Easter weekend wasn’t watching the Greatest Story Ever Told, The Robe, or other classic Easter movies. For me, it was watching Cecil B. Demille’s The Ten Commandments, starring Charleston Heston and Yul Brenner. I relished each time Brenner’s Ramses scowled at his viziers and exclaimed, “So let it be written, so let it be done.” My admiration for this cinematic villain was rivaled only by my admiration for Darth Vader. The annual viewing of the Exodus story is what cemented my Easter experience.

However, as a Black teenager growing up in the 1990s my relationship to The Ten Commandments changed. In an era influenced by Afrocentricity and politically conscious hip hop, this straightforward morality tale about slavery and freedom became complicated. The Egyptians were Africans, as my deep dive into Afrocentric literature revealed. And weren’t the Hebrews just foreign invaders who sought to form alliances with the enemies of ancient Kemet (Egypt)? Couple this with the breaking of the détente in the “Black-Jewish” relationship as the Nation of Islam’s Minister Louis Farrakhan and members of the American Jewish community were in the midst a rhetorical war of words over the historical record regarding Jewish participation in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade with the publication of the Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews. Now when I watched The Ten Commandments, I wasn’t so sure who was the hero and who was the villain.

Then something unexpected happened. I met a group of Hebrew Israelites from the Israeli School of Universal Practical Knowledge (ISUPK). To those unfamiliar—and even to those who are—the ISUPK are an enigmatic group. They believe that enslaved African and Indigenous populations of the western hemisphere are the genealogical descendants of the biblical Israelites. For the sake of space, I won’t go into all the particulars of their doctrine but suffice it to say that what drew me to this group was their iron-clad explanation for the existential and transgenerational suffering of Black and Indigenous people throughout the western hemisphere—or so I believed at the time.

Fast forward to the late 2000s and 2010s, with the advent of social media the beliefs of Hebrew Israelite groups such as the ISUPK have moved from public access TV stations to YouTube. Their teachings and beliefs have shifted from the margins of Black religious life to the mainstream. It’s not uncommon to hear an African American assert that “Black people are the true chosen people.” It’s become a regular occurrence for an African-American celebrity, entertainer, or athlete to post to their social media account that they’ve uncovered the “hidden truth” that Black people are “real Jews” to the chagrin of the mainstream media which, in a predictable knee jerk reaction, label them anti-Semites and hatemongers. Simply put, Hebrew Israelites are in style.

Within rabbinic Judaism, the High Holy Days (Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur) signify the most sacred period in the Jewish calendar. For Hebrew Israelites, however, Passover is the most symbolically important biblical holiday, as it’s the celebration of freedom over slavery. But more importantly it’s typological proof that the biblical God cares about Black people. For Hebrew Israelites, if God could hear the cries of their biblical ancestors then He will act again on behalf of their descendants in the urban centers of America, favelas of Brazil, shanties of Jamaica, and reservations of the American West.

For years, I would anticipate the arrival of spring and Passover season. Meticulously cleaning my house of leaven as I awaited this celebration of freedom. Now when I watched The Ten Commandments I was once again rooting for Moses (albeit a white one) and the Hebrews as they dueled with Ramses and the Egyptians.

But then something unexpected happened, I converted to rabbinic Judaism under the guidance of an African-American rabbi and within the context of a primarily African-American congregation. Observing the Passover seder communally with my congregation was exciting. As time progressed, however, Passover became further removed from my annual celebration of freedom from Egyptian slavery and the hope for the end of American bondage to debates over whether, as a non-Ashkenazi Jew, I should eat rice or not during the holiday and scavenger hunts for Kosher for Passover Coca-Cola. My conversion created a tension between my Black self and my Jewish self, and in the words of W.E.B. Du Bois, there were “two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

Although I do not think the sage of Great Barrington had me in mind when he penned those words in the Souls of Black Folk it was an apt description of the contested nature of my spiritual being. The more rabbinic I sought to become, the more Blackness was an issue in need of resolution.

The journey led me to leave my African-American congregation for a stint with Conservative Judaism and a flirtation with a local Chabad house to a trek to the North Side of Chicago to worship with Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews. Finally, I rounded out my trip with a brief fling with Reconstructionist Judaism, but the soul of my darker self became dimmer and dimmer with each stop—became almost unrecognizable to me. Eventually I abandoned the key tenet of Hebrew Israelite belief: that Black people in America were the lost tribes of Israel destined to languish and suffer in American captivity until God saw fit for our redemption.

Now I was Black and I was Jewish, but not a Black Jew—the two did not coexist together anymore. Jewishness could not explain my Blackness and vice versa. As a doctoral student in African-American Studies my research eventually led me to pose the previously unasked questions, Why was I Jewish? Did I need to be Jewish? If I was not Jewish because I was reclaiming my lost African ancestry, then why did I still need to be Jewish? While I loved Shabbat and Jewish holidays, keeping kosher, and living an overall observant lifestyle, the question remained: Why was I Jewish? The answer was equally unexpected: Passover had one final lesson to teach me.

Today I say that I transitioned from, rather than abandoned, Judaism. I learned that just as the Jewish people (which includes Africana Jews) throughout their history have created myths, rituals, and practices to survive and thrive through their persecutions, Black people in America have the same human right to create and tell sacred myths, develop rituals, and incorporate practices learned from others to ensure their survival.

I learned I need not be anybody else to be of spiritual worth. I learned I need not be “real,” “chosen,” or “lost”—that being Black is sufficient to be sacred. I learned that my prophets, sages, and saints could have names like Harriet, Martin, and Malcolm rather than just Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. I learned that Kwanzaa need not be from the distant African past to be of cultural and spiritual value. I came to value Juneteenth as a day of liberation that need not compete with or be a substitute for any other celebration of freedom.

Ultimately, from Passover I learned that every people should exercise the human right to tell their sacred story on their own terms, whether the rest of the world likes it or not. That is the meaning of freedom that I learned from Passover. “So let it be written, so let it be done!”