As has become increasingly clear to outside observers in recent years, conservative evangelicals don’t exactly have a stellar record when it comes to addressing sexual misconduct and various forms of abuse in their institutions. When the #ChurchToo movement emerged in 2018, and Jules Woodson spoke out about being sexually assaulted as a teenager by her then youth pastor, Andy Savage, Savage tried to get ahead of the story by admitting to a “sexual incident” in front of the congregation that employed him. In response, he was rewarded with a standing ovation. Although he resigned shortly thereafter, Savage went on to found a new church in 2019, where he continues to preach today, having never faced any sort of serious accountability for committing sexual misconduct with a minor.

Such incidents can easily be multiplied, and, with increased exposure of widespread abuse and concomitant sustained public scrutiny, evangelical individuals and organizations have been compelled to address the issue. While the good intentions of many evangelicals dedicated to curtailing abuse are not in doubt, whether evangelicals are capable of addressing abuse in a scaled and sustained way that will help protect potential victims is doubtful. The limits of evangelical imagination, framing, and ideology certainly militate against abuse prevention. And these limits are neatly illustrated in a recent article in Christianity Today by Kate Shellnutt, the evangelical magazine’s senior news editor.

Published under the dubious headline “Why Defining Gossip Matters in the Church’s Response to Abuse,” Shellnutt’s article—which, incidentally, never defines gossip—deals primarily with the broad issue of abuse of power in the Christian workplace. It focuses mainly on the case study of Ramsey Solutions, a popular evangelical financial planning company that is largely indistinguishable from the “ministry” and person of its founder, Dave Ramsey, whose hardline approach to debt is appealing to many conservative evangelicals.

Ramsey Solutions has been under fire of late for, for example, firing an employee whose wife merely posted to Facebook that she had concerns about her husband’s office reopening in a pandemic. In a typically evangelical authoritarian move, Ramsey Solutions deemed the social media post to be a violation of its “no-gossip” policy.

In fairness to Shellnutt and Christianity Today, highlighting this incident as an abuse of evangelical opposition to “gossip” is a good thing. In addition, Christianity Today should be acknowledged for calling for evangelicals to take accusations of sexual abuse seriously, when the magazine’s editors are highly aware that much of their readership will be inclined to dismiss rather than believe victims. That being said, the magazine remains very conservative, with its occasional milquetoast criticism of former abuser-in-chief Donald Trump being undermined by, for example, contributing editor Ed Stetzer writing explicitly of his support for the appointment of Brett Kavanaugh to a stolen Supreme Court seat.

Embodying this same vacillation between contradictory impulses, Shellnutt’s article reads somewhat like one of Tevye’s monologues in Fiddler on the Roof. “Christians are right to heed scriptural warnings about gossip, secrets, and lies,” Shellnutt tells us. On the other hand, “the American church has also seen a pattern of leaders referencing such teachings to silence and discredit victims and whistleblowers.” On the other hand, “the answer, Mitchell and other experts agree, is not for the church to stop preaching and teaching against the dangers of gossip.”

The evangelical obsession with appearances and reputation, which is just one of the many disciplinary mechanisms that work within the subculture to maintain the hierarchical (and abusive) status quo, is a thing to behold. Just ask any adult exvangelical about growing up with the pressure to exude positivity and to protect the reputation of the church—and, by extension, of Christianity, and, well, Jesus, I guess. Because a guy who has billions of adoring fans despite not being around for the last 2000 years clearly needs help protecting his reputation.

For a kid like me—introverted, gifted with a critical mind, and inclined to pessimism—the frequent exhortations from my mother to “be positive” and “work on not complaining so much” were a source of stress, and I had far from the worst of it. Even so, I’ll never forget the intensely hostile reaction I got from her and my sister when once, ca. 1994 in Colorado Springs, my in fact not-very-rebellious ca.-fourteen-year-old self answered an almost-certainly-Christian Wal-Mart greeter’s question about what we were there to purchase by quipping, “Boring Christian music.” I could have endangered someone’s salvation, you see! Even now, I roll my eyes at the memory.

And for all Shellnutt’s concern over addressing abuse around the concept of gossip, she fails to transcend this overwrought evangelical concern with appearance and reputation that so often conflicts with dedication to truth and justice, particularly when it comes to people who aren’t straight white men. But, in the words of the immortal LeVar Burton, “you don’t have to take my word for it”:

This is some serious tone-policing and guilt-tripping of abuse survivors in @kateshellnutt's article for @CTmagazine on gossip and abuse in evangelical faith communities. It's bullshit.

Shellnutt was irresponsible in publishing this without counterpoint.https://t.co/HOb6TbMGPW pic.twitter.com/kHcMxZzU5V

— R.L. Stollar (@RLStollar) April 21, 2021

Painting gossip as a worse sin than abuse guarantees that abuse will continue to decimate the church. I warned my abuser’s current pastor that he’s stalked young women in every congregation he’s attended. He treated it like hearsay even though I provided the names of fmr pastors.

— shannon: unglamorous mega-ministry monitor (@sunny_in_MN) April 21, 2021

"The vulnerable still need to be careful how they talk to the powerful; it's no excuse for taking the low road" is the most concise demonstration I've seen of why a sin-based rather than harm-based view of these problems collapses to a defense of the powerful.

— Actually, (@eaton) April 21, 2021

After reading exvangelical homeschooling survivor and children’s right’s advocate Ryan Stollar’s thoughts on Shellnutt’s article on Twitter, I asked if he might comment further for this piece. Stollar obliged, clarifying why he sees Shellnutt’s article as journalistically negligent:

Shellnutt’s article perpetuates some of the most damaging yet popular myths about abuse survivors in evangelicalism: myths like multiple witnesses are required to take abuse allegations seriously; discussing abuse allegations is cancel culture; false allegations are a common threat; and survivors must watch their tone in order to be taken seriously. It is irresponsible reporting to discuss those myths without counterpoints from experts in abuse prevention and survivor advocacy.

Stollar also sees evangelicals’ misplaced priorities regarding appearances at play in their responses to abuse. “All too often, evangelical abuse prevention is cosmetic rather than transformative,” he says. “It is made to mitigate a current situation of abuse instead of creating a truly safe environment.” Asked what the chances are that evangelicals will prove capable of creating such environments while keeping their “biblical worldview” intact, Stollar was pessimistic. Evangelical theology itself, in his view, is one of the root causes of the pervasiveness of abuse in evangelical environments, and most evangelicals are simply unwilling to face that fact.

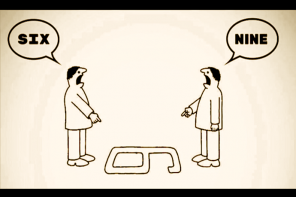

“It is evangelical theology and their concept of power that holds evangelicals back from addressing abuse,” Stollar maintains. “Evangelicals believe in divinely established hierarchies, and abuse thrives in hierarchical environments.” To riff on a parable from the Sermon on the Mount, most evangelicals are simply too concerned with the speck of sawdust in the eye of a “gossiper” to bother with the massive—and, I can’t help noting, phallic—plank that runs through their entire worldview, conveniently blocking abuse from their vision.

To be sure, spreading unsubstantiated rumors, which is a pretty standard definition of gossip, can be harmful, and to be clear, no one is making a blanket endorsement of that activity. At the same time, it’s undoubtedly the case that most evangelical concern about “gossip” only functions to protect the powerful, and that “gossip” itself is often used by the vulnerable to protect one another from abusers whose power and status shield them from accountability. By limiting herself to the loaded framework of “gossip” in her recent article, Shellnutt effectively ensures that her mild criticism, however well intentioned, will effect no change in the evangelical subculture and institutions in which she operates.