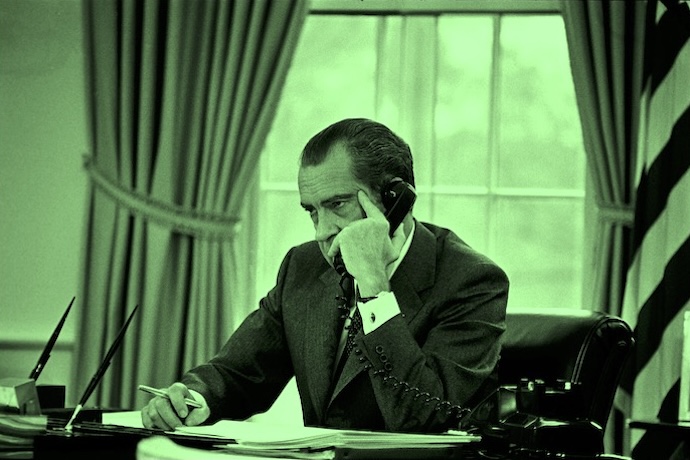

On August 16, 1971, White House Counsel John Dean circulated a confidential memo to Nixon loyalists titled “Dealing with our Political Enemies” which proposed a plan for the administration to best “use the available federal machinery to screw our political enemies.” The memo concluded that they didn’t need “an elaborate mechanism or game plan”—just an appointed project coordinator who would be understood to speak for the President.

When anything was needed from any of the federal agencies and departments the coordinator would use his delegated authority to strong-arm the department heads into doing things like denying grants and federal contracts, litigation, prosecution, and whatever else they could think of to undermine their enemies.

I recount this bit of sordid twentieth-century history for three reasons.

First, current talk from the President-elect and his team echoes that of its Nixonian precursor. According to NPR, Trump himself had made over a hundred threats to “prosecute or punish perceived enemies,” including President Biden and members of his family, VP Harris, former Representative Liz Cheney, and many others. Kash Patel, his pick to replace Christopher Wray as head of the FBI, has been even more explicit. In a 2023 interview with MAGA strategist Steve Bannon, Patel boasted:

We will go out and find the conspirators not just in government, but in the media. Yes, we’re going to come after the people in media who lied about American citizens, who helped Joe Biden rig the presidential elections.

Now facing what could be a messy confirmation fight, Patel has started to walk back his rhetoric. But the gist is clear enough.

Second, the Nixon-era enemies list was super secret, need-to-know, and shared only among a core group of conspirators. It only became public because of the Watergate hearings and special counsel investigation that led to Nixon’s resignation. The actions proposed by Dean, as well as those undertaken by the group that came to be known as the White House Plumbers, understood they were engaging in “dirty tricks” of the sort associated with covert operations in enemy territory. This is a far cry from Trump and his surrogates bragging about their intent to use the powers of government to screw their political enemies.

Third, the move from Nixon-era secretiveness to today’s public pronouncements reflects a loss of shame with respect to dictatorial desires. An enemies list and a bunch of cabinet appointments of ultra-loyalists who’ve been primed to pursue revenge is only a proximate goal. There’s every indication that what he desires, what he pretends to, is dictatorial power.

Trump’s admiration for authoritarian leaders like Vladimir Putin and Hungarian Viktor Orbán has become infamous. He has stated that he will “only” be a dictator on “day one” of a second presidency. The problem, of course, is that there’s no constitutional provision for any President to wield such authority, at least domestically, on day one or any other day.

The Constitution does grant the President broad powers in pursuit of foreign policy, particularly in wartime, when approved by Congress—as in the Authorization for Use of Military Force passed in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. But there’s no clear path for the President to invoke similar powers unilaterally inside the territorial United States.

While the history and precedents are murky, even a declaration of “martial law”—an idea that doesn’t appear in the Constitution—would most likely require congressional authorization. This lack of legal basis, of course, didn’t stop Trump back in 2020 from asking the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Mark Milley “Can’t you just shoot [police accountability protestors], just shoot them in the legs or something?”

Trump has vowed to govern through executive orders, pardons for loyalists, persecution of opponents, and so-called impoundment—the practice of refusing to spend funds allocated by Congress. Taken collectively and combined with his penchant to “deputize” far-right vigilantes with a wink and a nod, this is a program for makeshift autocracy.

Although these tactics fall short of an “enabling act,” which would legally grant the powers of a dictator, repeated exposure to violation of democratic norms undermines institutional trust. It discourages participation, leaving the would-be dictator more room to maneuver. Moreover, and worse still, support for authoritarian leadership increases in an emergency—genuine or manufactured.

With a very narrow majority in the House and only shaky and untested support for some of Trump’s more controversial nominees in the Senate, there’s significant room for both houses of Congress to assert their authority and insist on their constitutional responsibilities: advice and consent, control of the purse, and legislation. But we cannot expect institutional actors—in Congress, the courts, or the bureaucracy—to stand up to a potential avalanche of policies, personnel decisions, pardons, exhortations, and signals of impunity without real pressure from the people.