In the 1970s, conservative evangelicals declared themselves defenders of the American way and protectors of the moral majority. Thus began a long and bitter culture war for the soul of America. Among the stoutest of the Christian soldiers was the Southern Baptist Convention’s lobbying and education arm, the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission (ERLC).

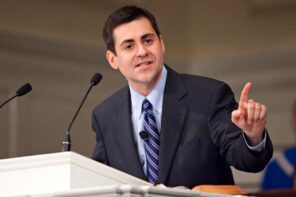

Until recently the commission’s statement of vision had as its goal: an American society that affirms and practices Judeo-Christian values rooted in biblical authority. But that vision is being abandoned by the Southern Baptists and by a lot of other evangelicals. Among them is the 44-year-old president of the ERLC, Russell Moore. In a recent interview, we talked about why that is.

For starters, the religious right has lost the cultural war on every front. Abortion is the only standout and even there success has been at the margins. Their goal of making all abortion illegal isn’t close to being achieved.

America has gone the other way in so many instances that it’s hard to count them all. Science, technology, courts, legislatures and public opinion have all worked against them (see graphic below). The array of forces has been so overwhelming that believers with less surety might have begun wondering if God really was on their side. Instead a new generation of leaders is arising with some different ideas and tactics. While not conceding utter defeat—and certainly a long way from surrender—they all admit it is not looking too good right now.

The first order of business? Face the facts.

“The Bible Belt is collapsing. The world of nominal cultural Christianity that took the American dream and added Jesus to it in order to say you can have everything you’ve ever wanted and heaven too is soon to be gone and good riddance,” Moore said when he took over the ERLC in 2013: “We’ll be stronger without nominal believers who have been following a civil religion as though it was the gospel.”

What Moore knows and some pollsters may not is that it’s a lot easier to find people who say they are evangelicals than it is to find people who truly believe evangelical principles—it’s a lot easier to find their names on a church roll than it is to find them in church. In conservative communities across America, Christianity is often melded into a kind of American triumphalism that has little to do with the Bible.

As I have noted elsewhere, it is very possible that only about seven percent of Americans are actually the kind of conservative evangelicals portrayed in the media. When evangelical pollster George Barna gave respondents a straightforward test of standard evangelical beliefs, he found the same percentage.

Although Moore probably wouldn’t agree to those numbers—the Southern Baptist Convention still counts itself as having 15 million members—he is telling his people to stop thinking that America is going their way. It’s clearly not. Don’t try to fit in, he tells his flock. “We’re not to be conformed to the pattern of the world. We’re always to be strangers and exiles in any cultural context,” he preaches.

America isn’t a Christian nation and never was, he says: “Stop trying to go back to Mayberry. The road to Mayberry and the road to Gomorrah are the same road.” Focus forward to eternity, where Christians will be the winners, says Moore.

Next, Moore tells his flock to clean up their own houses. Stop fighting over minor matters like whether people say “Merry Christmas” or “Happy Holidays,” for instance—people who aren’t Christians don’t have conservative evangelical values, and there’s no reason that they should.

And stop threatening America with destruction if it doesn’t act like a Christian nation. “That’s nothing but a national prosperity gospel,” he believes.

Those who are listening to Moore tend to be younger evangelicals who also generally want more separation from the Republican Party. “There’s a whole generation of guys coming up saying we’re tired of being the lapdogs of the GOP and worse than that, being tossed away like a Kleenex after the election is over,” Ryan Abernathy, teaching pastor at West Metro Community Church in Yukon, OK, told me.

They want to address a broader range of issues: immigration reform, poverty, and racial reconciliation.

Moore demonstrated the new approach by meeting with President Obama to urge immigration reform. He promised to pray for the president and said he loved him, although they disagree on many issues. In the Wall Street Journal, he spoke out against Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant slurs. And he called for the Confederate flag to be taken down from the South Carolina capitol.

Such positions sometimes cause older members to grumble that times were better with Moore’s predecessor, Richard Land, who publically supported Mitt Romney in the last presidential election, did not meet with Obama and wasn’t always gentle with those who disagreed.

One observer and frequent blogger, Bart Barber pastor of First Baptist Church in Farmersville, Texas, told me that the change isn’t as stark as it seems: “From what I’ve been able to see, Richard Land and Russell Moore are in exactly the same place on issues.”

Perhaps. But some things do look different. When Farmersville was recently embroiled in a bitter controversy over whether a Muslim cemetery could open in the little North Texas town, the town’s two Baptist pastors were on opposite sides. Barber, who generally subscribes to Moore’s new thinking, supported the Muslims, seeing it as a freedom of religion matter, while the pastor across town vehemently opposed the cemetery.

St. Augustine at Gay Pride?

Moore is asking evangelicals to be nicer to people they disagree with, keeping in mind that anybody can accept Christ and be transformed.

In a recent radio interview he said:

The next Billy Graham might be passed out drunk right now. And the next Mother Theresa might be running a Planned Parenthood clinic right now and the next Augustine might be at the front of a gay pride parade right now And if we see people in those terms, we’re going to be speaking in ways that seek to persuade and not just in ways that seek to score points and to vaporize our opponents.

But he’s a long way from declaring universal brotherhood. When I referred in passing to his stated wish for evangelicals to remember that their opponents were brothers and sisters in Christ Moore corrected me firmly: “…potential brothers and sisters in Christ.”

He frequently talks about justice, but he isn’t usually using the term in the way progressives do. By justice, Moore means “religious liberty,” specifically exemptions from certain laws. Conservative evangelicals have supported lawsuits to allow Muslims and others to dress and wear beards according to their religious understanding. But abortion rights and gay rights laws are still a focus of their legal appeals. Moore predicts that the next flash points will be school accreditation and tax exemption.

“Religious liberty isn’t a question of exemption from laws. It’s a question of the government demonstrating a compelling reason as to why it ought to override religious convictions,” Moore told me.

In the matter of basic theology, Moore says holding to strict interpretations of the Bible is as important as it has ever been. Tolerance for sin is unacceptable. He’s counting on what he calls “convictional kindness” to bring Americans back to church.

“I don’t think the sexual revolution can keep its promise,” he told me,

so what I’ve been saying to our churches is that we need to be ready to receive refugees from the sexual revolution. Two kinds of Christians won’t be able to speak to those refugees: a church that has abandoned the Scriptures and a church that screams at or demonizes people on the outside.

By hewing to their principles and refusing to be moved, conservative evangelicals have been able to keep conversation contentious on issues where they believe the country has gone wrong. “The pro-life movement is still alive and vibrant in ways that no one would have assumed in 1973,” Moore said.

Evangelical strategy on gay rights is much the same: keep protesting in every way possible until the culture swings their way again.

Divorce is another area where Moore claims some success. Rates are still high, “but divorce is not spoken of as it was in 1960s and 1970s when many minimized the damage that could be done to children and families by no fault divorce. There is a recognition that divorce is not the instrument of self actualization that many people thought it was,” he told me.

Moore’s ideas are intriguing, especially because he’s speaking in an arena where new ideas have often seemed anathema.

Screaming and demonizing, as Moore put it, are time-honored methods for bringing sinners to Jesus. So for Moore to pull back from those tactics is no small move. But when he talks about churches that have abandoned scripture having nothing for the unsaved, what he’s really saying is that for the Gospel to have any power it must be confined to a very particular (and immutable) interpretation of scripture—one with plenty of judgment and wrath.

That kind of scriptural adherence may bring droves of Americans back to the conservative Christian fold, as it has in previous centuries. But I keep thinking about a book called unChristian written by some George Barna researchers in 2007. In their surveys of non-Christians they found that evangelicals’ emphasis on telling sinners the Good News wasn’t convincing anyone.

“We’ve heard the Good News,” the non-saved said, “and we’ve also met Christians. We don’t want to be like them.”

Will Americans want to be like evangelicals if they’re just as judgmental just…nicer?

We’ll see.

__________

Here’s a visual take on the state of the culture wars: