For a decade and a half, Dr. Jeffrey J. Kripal has been advocating for the field of religious studies to not only take reports of alien abductions and visits from the dead as seriously as accounts of miracles, but to ask very different questions about “impossible” experiences and phenomena. His research suggests that these questions have actually haunted the humanities since the beginning, and they may be essential to saving the future of the humanities from obscurity and defunding.

How to Think Impossibly: About Souls, Ufos, Time, Belief, and Everything Else

Jeffrey J. Kripal

University of Chicago Press

July, 2024

Despite this singular body of work, How to Think Impossibly may be Kripal’s strangest book yet. It describes encounters with mantis-like aliens and other things that serious scholars aren’t supposed to take seriously. But Kripal clearly believes that religion scholars have no right to analyze the experiences of saints and mystics while scoffing at reports of ghosts and UFOs. It’s what prompted him to launch Rice University’s “Archives of the Impossible,” which collects documentation on “historical events and common human experiences that are not supposed to happen but clearly do.” Perhaps these impossible things aren’t quite so impossible if we’re willing to question our assumptions about time, the universe, and ourselves. For Kripal, such a reassessment doesn’t involve being uncritical, but rather doubly critical: It entails taking the hermeneutics of suspicion that has saturated the humanities and turning it back on scholars, challenging them to question their assumptions and take stock of their exclusions.

In our recent interview, an edited and condensed version of which appears below, Kripal shares his theory on why impossible things happen, suggests that altered states may help us understand certain texts, and addresses some of the criticisms he’s likely to receive.

You talk a lot about “ontological shock,” a theme that runs through the various experiences recorded in the “Archives of the Impossible.” It’s also a theme among the many people who contact you about their psychic premonitions, UFO encounters, and abductions by giant mantis-like creatures. Can you talk about the concept of “ontological shock” and why it’s so important for thinking impossibly?

The phrase entered American culture through The Matrix (1999) [whose soundtrack featured a track titled “Ontological Shock”] and, most recently, through the retired intelligence officer David Grusch and his whistleblower statements around the reality of the UFO or UAP.

UAP from footage confirmed by the Pentagon to have been taken by the US Navy. Image: Jeremy Corbell/YouTube

But the phrase “ontological shock” actually goes back to Paul Tillich’s attempt to make some theological sense of what happens in such a dramatic moment, which often, as he noted, shows itself in two ways—an ecstatic or overcoming position, and a terrifying, fear-filled, or negative position.

It was John Mack, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Harvard psychiatrist (whom Harvard literally tried to fire for his public interest in “alien abductions”), who made the expression well known in the 1990s. This was after his close interaction with actual experiencers, who showed no real psychopathology (which is what Mack expected) and often described how their sense of fundamental reality was permanently altered, really shattered, by what happened to them. Hence “ontological shock.”

I think the fuller humanist history and philosophical notion of “ontological shock” is very important to the study of religion because (a) it’s “ours” (that is, Tillich coined it right before the comparative study of religion was getting off the ground, as it were, in the States); and (b) this is precisely what the experiencers consider to be the most important aspect of what happened to them—it’s the very meaning and future direction of the historical event.

I confess that I don’t know how we take these human beings or these histories seriously and not engage their ontological shock honestly and forthrightly; which is to say, not only as a “cultural representation” or “discursive strategy,” or whatever (at-arms-length) move we make to study these events evenly and fairly. It’s really, at the end of the day, a moral position. It’s about taking human beings—all of them—seriously as visionaries and potential co-thinkers and co-theorists of some future paradigm shift. (And Thomas Kuhn, by the way, was a childhood chum of John Mack.)

You write that humanities scholars need to make better use of the “experience-source hypothesis.” Can you explain what this is and why it matters?

This is basically the idea, taken from the work of the folklorist and medical humanist David Hufford, that the exotic or extraordinary claims of the religions (however strange or radical) really matter and should be treated as the ultimate source of religious belief and practice. That these claims come from the exotic or extraordinary nature of human experience itself, not only from culture and history (although, of course, those matter a great deal, too, since they shape, limit, and direct that very experience). Please note that such an experience-source hypothesis does not, however, entail “believing the beliefs” or signing one’s name to the content or structure of the experience.

Of course, this experiential foundation is often very distant and barely visible. But it’s exactly such experiences, in this model at least, that in turn generate religious ideation through a thousand social, psychological, and historical channels, which we know a great deal about.

Let me give a concrete example. In this methodological view, the nearly universal religious notion of a “separable soul” that survives physical death didn’t come from the hallucinatory and false dreams of “savages,” as anthropologist E. B. Tylor thought. This is not only racist, it’s fundamentally wrong, as an honest look at the NDE [near-death experience] literature in the US can suggest in great detail. After such a long review (I’m imagining years of reading, not a few essays this afternoon), it’s much more likely that the belief in a separable soul came from the same types of experiences just as evident today as they were in the “ancient” world.

Human beings have long encountered loved ones after they died—in, yes, dreams, but also in physical form (yep), vision, and out-of-body experiences. And human beings continue to experience such things to this very day. Widows see and interact with “dead” husbands, for example. This is not an “opinion,” this is simply so.

It’s these kinds of extreme or “impossible” events that the book is most interested in focusing on as the source of new theory and thought. This is not religion as practiced. This isn’t even “religion” in many ways, as these experiences often conflict with or collide with religious belief and tradition. But these moments definitely include (really rely on) profound moments of “transcendence”—in this case a transcendence from social embodiment.

If the American Academy of Religion conference is any indication, there’s no clear consensus about what exactly religious studies is supposed to be doing. But I think many people wouldn’t recognize what you’re doing in this book as religious studies. Do you consider this work to still be religious studies, or something else like theology, metaphysics, or some new field like “impossible studies?”

The study of religion of the 1960s wasn’t the study of religion of the 1990s—which isn’t the study of religion of the 2020s. The study of religion is whatever we say it is. We get to decide. I reject the notion that I’m not doing “religious studies” (although, I confess, I despise this expression, as it sends all the wrong signals to our students and their parents). Once again: says who? Says someone who thinks the study of religion should look like it did when they were trained in the 1990s? Why are your graduate mentors suddenly omniscient? Why are those authors, whoever they are, now infallible absolute gods? Can’t you think outside your specific truths and authors? That is how to think impossibly. Let go of your worldview, whatever it is.

You write provocatively that, “I will pull no punches. This is a book about why the humanities must stop ceding reality to the sciences.” Can you explain why the humanities ought to have a say, not just about culture, but about the nature of reality?

I spent four years in a Dean’s Office as an associate dean. I am deeply worried about the humanities. I love intellectuals, and I will always fight for the honesty and integrity of their positions, whatever those are. But this is also why I feel free to criticize colleagues. I would say that there’s an intellectual or theoretical issue (our colleagues are right about so many things), and there’s a public marketing concern (trust me: the humanities are losing). These are different concerns.

NGC 1866 is a star cluster made up of hundreds of thousands of stars bound together by gravity. Individual stars in some clusters are so old they were some of the first to form after the Big Bang. Image: ESA/Hubble & NASA

To take up the latter, we’re losing the cultural conversation, spectacularly. We’re being ignored, and often for good reason. What do we, really, have to say that’s useful, positive, and attractive to the public? The answer: very little, or nothing at all. We criticize, criticize, and criticize, and those critical theories, as Rita Felski has taught us, are largely parasitic. They don’t stand on their own. Accordingly, humanists are too often the bummers in the room. Of course, no one wants to listen to us.

The problem is that all of these criticisms are entirely just, spot-on. I don’t have any criticism of the criticisms. They seem exactly right to me—more than right, actually. But in the meantime, the scientists are talking about what happened microseconds after the Big Bang, to everything and everyone. They’re making universal statements all the time. Indeed, science doesn’t work without this cosmic universalism. What happens across the galaxy works by the same exact physics as what happens in your body, right here, right now.

This is why we’re losing, why we’re ceding reality to the sciences. Paradoxically, we actually “have” all the weird stuff, which is to say the paranormal and religious stuff (and the “ontological shock” discussed earlier), but we won’t use it. We won’t think with it. We look away. We deny. We ignore. But why? I suspect, on some level, that we don’t want to be heard; that we’re protecting ourselves from public attention and therefore public censure. As a censured public intellectual, I get that. I honor that. But I worry about that choice, and I think many people are smarter than we imagine, more ready than we realize.

In Authors of the Impossible (2011) you began asking serious questions about the paranormal. You also asked why religious studies—which has spent years analyzing textual accounts of miracles and hagiographies of saints and mystics doing impossible things—has ignored these questions. In How to Think Impossibly you write that you “lay your cards on the table.” You have a hypothesis that accounts for all paranormal phenomena, from UFOs to psychic ability to ghosts. It involves “the fundamental unity of space, time, and mind” as well as “the human as two.” Can you succinctly explain your theory of why impossible things happen and have always happened?

Because this is what a human being is. The human being experiences “the impossible,” because the human being, everywhere and always, is not the culture and history of the place and time. We exceed and exhaust our historical conditions, each and every worldview, no matter what it is.

This is also what I mean by the “Human as Two.” I don’t mean there are two substances. I mean that we are the splitters of reality. We cognize, perceive, and imagine that there are “subjects” and “objects,” but this is an illusion created by our very existence, by our very cognitions, perceptions, and imaginations. Reality is actually One, and until humanists can say that, we will not be heard. We will be ignored. And we should be.

You write “My books, and maybe my entire lifework, has been about one thing: teaching humans how to be God and God how to be humans.” This is quite a statement! Can you help readers begin to understand what this means?

Human beings have commonly experienced themselves as gods, or as God. This is the history of religions. It’s certainly the histories of Christianity. But these same human beings have often been tortured, pursued, condemned, or called crazy. It’s also true that the history of human deification is rife with very bad moral choices. “God” doesn’t seem to know how to be a “human being”—not justly anyway, not equally in terms of class, race, gender, sexuality, and religion, which are our awakening, our contribution to the human story. The truth is that mystical traditions and modern moralities don’t often go together. I think we should say that.

This is where my critical sensibility around these categories shows itself. I think people forget that I was the model of the harassed and threatened scholar of religion in the 1990s, and for psychoanalytic or Freudian reasons. I was the scandalous reductive thinker. I reached out to other threatened intellectuals. I know, intimately and from long experience, that religions and cultures do not long endure such intellectuals. I’ve never forgotten that experience of being exiled, of being, frankly, hated. This is why I’m so deeply suspicious of all things “religious,” but also of all things “cultural.” This is why I’m fundamentally counter-cultural. All cultures, all religions.

In your conclusion you write, “Thinking impossibly is not possible for everyone” and describe it as “academic Gnosticism.” This will probably enrage some of your critics. They’ll point out that the burden of proof is on the person making the claim. Or they may accuse you of a “special pleading” fallacy, whereby your ideas can only be evaluated by those inclined to agree with them. They may even say that “academic Gnosticism” is an oxymoron because the knowledge produced by the academy and the spiritual knowledge received though gnosis are mutually exclusive. Do you simply no longer care what these people think? Or is there still some middle ground from where your critics might be able to see the value in what you’re proposing?

My critics can say what they think, and I hope and trust they will. But I will always point out that we’re losing—big-time—the cultural conversation, and partly because of these same criticisms. They have their jobs and their tenure, and I honor that. I like that as a former associate dean who handled promotion and tenure cases and wrote for countless individuals, often behind the institutional scenes. But the students of such critics will not find jobs, much less tenure, since the disciplines will wither away—partly, I’m arguing, because of this refusal to think impossibly.

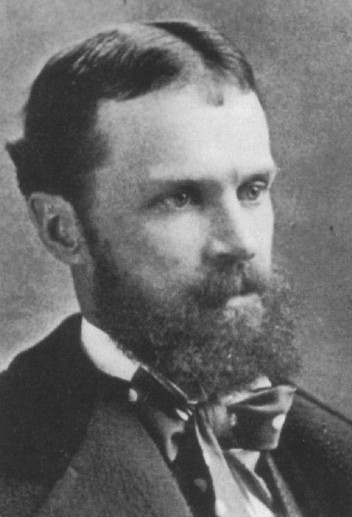

Willam James’ fascination with mysticism was influenced by his experience with nitrous oxide, which he described as “an intense metaphysical illumination.”

I’ve tried to re-vision and renew the conversation through the notion of the “superhumanities,” by which I mean the humanities as altered states and the human as superhuman (and, yes, this is Friedrich Nietzsche, but it’s also William James and Gloria Anzaldúa). I mean to point to the fact—I really think it’s an obvious fact—that some of our most influential authors, artists, and activists came to their convictions through altered states (psychedelic states, near-death experiences, moments of reading-realization, moments of philosophical revelation), and those same altered states are then coded in their books or works of art. The human is always overcoming itself, becoming something else or More, to use Nietzschean or Jamesian terminology (again based very much on their own altered states).

There’s this very funny story about William James. I have no idea if it’s true, but it speaks to this directly. The story goes like this: James couldn’t understand Hegel, until, that is, he took a psychoactive substance. Then he could suddenly and fully understand Hegel. Until, alas, the substance wore off. Then James could no longer understand Hegel.

The story is so powerful (and funny) for me, partly because I don’t understand Hegel (there’s an understatement), but also because it gives witness to the basic argument that there are altered states embedded in classic humanist thinkers and texts, and understanding these ideas require altered states to make sense of them. These, of course, are not the same altered states. Hence the different readings. But these texts, please note, are smoldering superhuman texts (I borrow the phrase from Charles Stang of Harvard Divinity School). They can catalyze in their ready readers something of the original altered states that produced them. This reading-realization is the superhumanities.

This is also what I mean by “academic Gnosticism.” One of the chapters of How to Think Impossibly I co-wrote with a neurodiverse or self-described “autistic” individual named Kevin. Kevin sees things and knows things that I don’t see or know. That’s not an “opinion” of mine. That is simply so. There is gnosis, or direct knowledge, and I do not have it. But I can read it, sense it in Kevin. That, once again, is the power of the superhumanities.

Why is this controversial? Some human beings of course know things that other human beings don’t know. This is why How to Think Impossibly is, first and foremost, a thinking-with these gifted individuals. I am not so gifted, but I can think-with them. I can also realize or grok something of their experiences in the texts that they write out of and because of their own altered states—probably because of my knowledge of the history of religions. None of this seems the least bit strange or “extraordinary” to me. It seems obvious, again.

Finally, let me say this. I explore all of the ideas above much further, and much more fully, in the book. I guess I’m a bit shy about such interviews, but I also see their relevance and importance. Hence my grateful participation, with the proviso of “please read the book.”