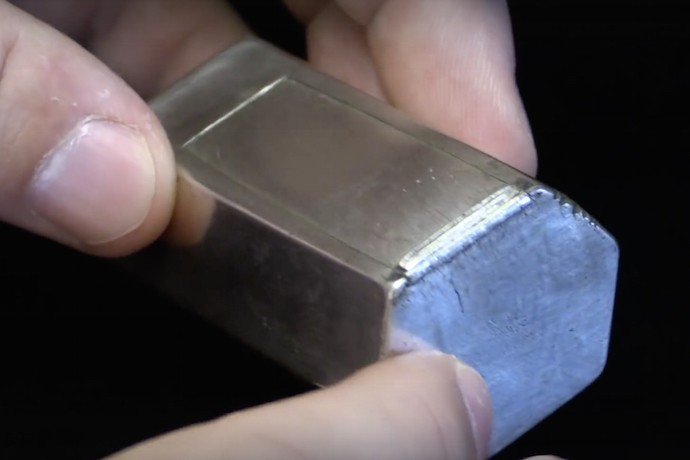

It’s a news story that contains the ingredients of a paperback thriller, the sort of thing that reminds readers what they find so evocative about archeology. Researchers sifting through the ground at America’s first permanent English colony at Jamestown Virginia discovered, atop the coffin of one of its prominent members, a green-patina-covered box mysteriously emblazoned with the letter “M.”

An electron microscope revealed that the still unopened box contains several shards of bone—seemingly evidence that Captain Gabriel Archer was entombed around 1609 with some sort of relic. Evidence of crypto-Catholicism here in what was presumed to be a uniformly Protestant colony.

In the religious origin-myth of America, Protestantism has played a central role. Since John Winthrop declared the American errand into the wilderness as being a “city upon a hill,” to current debates, Protestantism is a central feature in most conceptions of America. The recent archeological discovery at Jamestown Virginia would seem to complicate that popular view.

Archer, along with several others whose bodies were recently recovered, were among the first English settlers who came to America during an era the poet John Donne described in a sermon to the Virginia Company in London as marked by “a flood, a flood of blood.” Indeed, accounts such as John Smith’s held that the desperate colonists in the settlement had turned to cannibalism, something verified by archeologists in 2012. This latest news is the biggest story about Jamestown since that grim announcement three years ago.

The Atlantic asserts that, “The finding is a historical bombshell,” while James Horn, the director of Jamestown Rediscovery, told the Washington Post that, “It’s the most remarkable archaeology discovery of recent years…. It’s a huge deal.” Describing the box as a “sacred object of great significance,” Horn believes that it’s clear evidence of Archer’s crypto-Catholic allegiances in Protestant England’s first American colony. The Post conjectures that Archer may have been the leader of a secret Catholic cell, and the Atlantic wonders whether disagreements between Archer and Smith were fundamentally based on sectarianism and not simple politics, as has been widely assumed.

This kind of speculation makes for a good story, but it’s important to be cautious. If the object found with Captain Archer is indeed a Catholic reliquary, and if indeed it was buried with him because of recusant beliefs, then this certainly is interesting and important news. But even should that prove to be the case, claims that it “could rewrite our understanding of the intersection of religious and cultural identities in colonial America” should be viewed with skepticism.

To depart from a solely Protestant conception of early American religious identity doesn’t require the discovery of crypto-Catholicism in Jamestown—interesting though it would be. Secondary education in the U.S. may still emphasize a Protestant triumphalist version of early American history focusing on the mythopoetic significance of Plymouth Rock and the pilgrims to the exclusion of others, but academics working across disciplines, such as Alan Taylor, David Fischer, and Peter Silver, have emphasized the religious, ideological, and ethnic diversity of early America for decades.

The possibility that a secret Mass may have been celebrated at Jamestown is indeed interesting, but it doesn’t change the fact that the very first American masses were celebrated by Spanish colonists more than a century before, and that indeed the first Protestant services were not held by the English but by French Huguenots in 1564 at Fort Caroline (today St. Augustine Florida).

In understanding the complexity of early American religion one also needs to take into account the presence of Yoruba and Igbo believers, as well as Muslims, first brought into the English speaking colonies as African slaves a decade after Archer died. One should also consider the intricacies in New England religion (which didn’t just contain monolithic Puritanism), with disagreements among Calvinists and the presence of High Church Cavalier Anglicanism in Merrymount, not to speak of the varied denominations in the middle colonies of New York and Pennsylvania.

And there is always the possibility, which both articles do consider, that the supposed reliquary may not be evidence of Catholicism at all. The Elizabethan settlements of religion, though often oppressive, were more tolerant of crypto-Catholic practices among Protestants than later regimes, as long as allegiance to the sovereign was maintained. This often involved appropriation of Catholic paraphernalia towards nationalist ends (such as Elizabeth’s use of Marian imagery).

During the Jacobean and into the Caroline era there was often no inconsistency between some variation of seeming Catholic devotion and a Protestant conscience.

So while the discovery could be interesting and meaningful, calling it a paradigm shift in understanding betrays an outmoded, Protestant-centric framework refuted by a great deal more (and a great deal more compelling) evidence. In any case, that shift has been occurring in scholarship for a half century. To paraphrase John 14:2, in America’s City on a Hill there have always been many mansions.