Some ten days after the fall of Kabul it’s still not clear how the Taliban will rule. There are several reports of reprisal killings and brutal enforcement of their strict interpretation of Islamic law. But there are also statements of support for women’s rights, protection from reprisals, and overtures of the Taliban leadership to former Afghan leaders like Hamid Karzai to create a coalition government. More significantly, for over a week the Taliban stood aside while 50,000 foreigners and their Afghan supporters were airlifted from the Kabul airport.

The question is whether the Taliban has changed. Will it be the same hard line Islamic state that it tried to create the last time it was in power, twenty years ago? Many are, quite justifiably, skeptical of what Human Rights Watch’s Heather Barr called a “charm offensive” in an article noting that while there will be no “discrimination” against women they will be living within the “framework” of Islam, which of course has numerous interpretations.

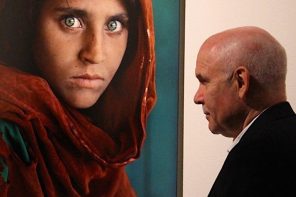

But even if the Taliban doesn’t want to change it might have to. For one thing, Afghanistan isn’t the same place as it was twenty years ago when ruling it was more of a pushover. Now it’ll have to adapt to some degree to its new freedom-loving urban constituency. Throughout Afghanistan people have cell phones and access to the internet. It’ll be difficult to have the same kind of social control two decades later.

Another factor is the way the Taliban came to power in recent months. In February 2020, then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo represented President Donald Trump in meetings with Taliban representatives in Qatar. Trump essentially surrendered to the Taliban in exchange for assurances that the US would withdraw peaceably. The US. then drew down its military presence to a tiny fraction of what it had been before, and with no assurances given to the Afghan government (which wasn’t even a party to the negotiations), the US agreed to withdraw all of its troops by mid-2021.

This was an enormously generous gift to the Taliban. They knew that Biden’s hands would be tied to the Trump decision—if he didn’t pull out the last US troops in mid-2021 as promised, the Taliban would militarily attack the paltry 2500 remaining troops and, assuming that the Afghan military wasn’t capable of resisting the Taliban (as was clearly demonstrated in the final weeks before the fall of Kabul) Biden’s only choice would be to ramp up the US military presence to a fighting force of 100,000 or so to protect the remaining 2500. There was very little stomach among the American people for yet more war in Afghanistan, an opinion shared by Biden himself. So he bit the bullet and withdrew the last remaining troops, and the world has witnessed the consequence.

For the Taliban, however, the Trump deal was a godsend. Not only did it hand them the country without needing to fight the US, but also it gave them time to make deals with regional warlords, tribal leaders, and Afghan military commanders to allow them safe harbor (and in some cases plum positions) if they agreed to change sides at the appropriate moment.

That moment came in August, when the new American President, Joe Biden, announced the withdrawal of the last troops. Methodically, region by region, the resistance fell within days like a house of cards, virtually without firing a shot. At the end, the Taliban simply marched into Kabul and took over.

This patient pattern of negotiation and coalition-building, however, has changed the Taliban. Although the movement continues to give voice to the extremist Islamic ideology for which it is justly infamous, it has also tempered its talk, in part to mollify its coalition partners. It remains to be seen if their support will be dropped as soon as the Taliban has secured its hold on the political apparatus of the country, but assuming they continue to need this support their extreme position will be at least partially checked.

One reason why it would be in the Taliban’s interest to maintain good relations with its internal coalition and with international connections such as Russia and Pakistan is that it remembers what happened twenty years ago. At that time an intensive US military assault was able to destroy the Taliban’s control as quickly as the American-supported Afghan government collapsed in 2021. In both cases the critical issue was a withdrawal of support from tribal warlords and regional leaders in what had been tacit support. The Taliban is mindful that this could happen again.

An indication that the Taliban leaders are taking a more prudent course is its approach to the US evacuations at the Kabul airport. They appear to have been in no mood to confront the might of the US military, especially since they’d been assured that it was going to leave. Instead, the Taliban leaders adopted a position of patience. They proclaimed that there would be no reprisals and free access to the airport. With some truly unfortunate exceptions, this promise was largely met.

Compare this to the last time the US lost a war and had to suddenly retreat during the fall of Saigon. During that memorable scramble in 1975, US diplomats had to evacuate the embassy via helicopters that landed on the roof as the North Vietnamese army tanks literally broke down the Embassy gates. The airport was out of commission since the North Vietnamese military had attacked it, and in fact the last American soldiers to lose their lives in the war were defending the airport. After that last helicopter flight not a single person was evacuated by the US military. The “boat people” who fled Vietnam did so on their own.

By contrast the Taliban has been remarkably patient. The airport hasn’t been bombarded, and tens of thousands of Afghan people have been able to board US military cargo planes. Though some Taliban soldiers have made the exit difficult, others have helped to control the crowds and check their documents to make certain that the papers of those trying to leave were in order. Understandably, however, tens of thousands of Afghan citizens who would like to leave the country simply to have a better life abroad were not able to do so.

For many of them, especially those who have come to enjoy the secular lifestyle that’s developed in Afghanistan’s cities in the past twenty years, the question is whether the Taliban will rule like another Islamic State (ISIS). In this regard it is interesting to note that there is in fact an indigenous movement in Afghanistan that calls itself ISIS-Khorasan (Khorasan is the 6th century designation for a region that stretched from Eastern Iran through Afghanistan to Central Asia). But this ISIS-K is led by renegade former Taliban militants, and is a rival of the Taliban, so they will likely try to co-opt or destroy it.

So the Taliban will not become ISIS, but it could rule like ISIS, as it did twenty years ago, or it could change along the lines that it has professed it would, and which its coalition and urban centers might welcome. Whether one thinks that that’s possible depends in part on whether one thinks a religious regime of this sort is capable of internal change without the necessity for an invasion from outside.

The diversity of political positions within the Islamic Republic of Iran give some indication that even a rather rigid religious regime is indeed capable of flexibility and perhaps significant change on its own. Muslim militants in other parts of the world have disagreed with Ayatollah Khomeini and rejected many of his positions. Post-revolution leaders in Iran, including Mohammad Khatami, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, and Hassan Rouhani have been considerably more moderate than the extremists. Saudi Arabia is another hardline autocratic country that seems to tolerate a certain degree of dissention and liberal lifestyles—at least in private.

The leaders of the Taliban claim that now that they’re in charge they want a new leadership style, one that will create a stable respectable government, albeit one with strong Muslim religious limitations. We’ll see if this promise is fulfilled. But if Afghanistan does turn out to be like Iran or Saudi Arabia, then there’s another question: whether the US can live with it, and if so, whether it accepts that its twenty years of attempts to transform Afghanistan have at least in part succeeded.

That may be the enduring legacy of the long US occupation: a more moderate Taliban. Whether this was worth the trillions of dollars spent and lives lost in maintaining the occupation all these years will be debated for some time to come. And, of course, it remains to be seen whether this moderate stance will last.