During our season of political madness, it took a lot to trigger a double-take, and yet a pro-Trump, Covid-denialist pediatrician named Stella Immanuel declaring that illness was caused by the semen of demons was an exemplary case. Dr. Immanuel first came to public attention after speaking on the steps of the Supreme Court where, as part of a group calling itself America’s Frontline Doctors, she advocated for disproven hydroxychloroquine treatments. Many noted that this was the least of her unconventional medical opinions, including Will Sommer of The Daily Beast who wrote that she “has often claimed that gynecological problems like cysts and endometriosis are in fact caused by people having sex in their dreams with demons.”

Liberal Twitter understandably snarked, but too much laughing can drown out just how disturbingly prevalent such beliefs are. For example, Reverend Paula White, televangelist and former advisor to Donald Trump’s Faith and Opportunity Initiative, claimed that those who opposed the former president were members of “demonic confederacies,” according to Frederick Clarkson here on RD.

Clarkson explains that White and those like her subscribe to an apocalyptic and anti-democratic worldview which understands its adherents as being soldiers engaged in “spiritual warfare” against the “demons” of the Democratic Party, the LGBTQ rights movement, Planned Parenthood, Black Lives Matter, universities, media, the medical establishment and so on.

There are dangerous consequences to such demonization. Andrew Seidel recently told RD’s Chrissy Stroop that Christian Nationalism “created a moral permission structure that granted the insurrectionists a mental and moral license to attack our government and attempt to overthrow a free and fair election.” Christopher Douglas agrees, writing that “‘demoncrat’ is an occasional slur among conservatives.”

Meanwhile, a recent poll from PRRI indicates that 18% of Americans believe that the “government, media and financial worlds… are controlled by a group of Satan-worshiping pedophiles who run a global child-sex trafficking operation,” claiming that everyone from Hilary Clinton to Tom Hanks are involved.

Beliefs associated with the cult-like QAnon movement have a long lineage, with elements drawn from imaginary fears concerning Black Masses, witches’ sabbaths, and the antisemitic blood libel. In Medieval and early modern Europe, Christians figuratively and literally conflated Jews, Muslims, pagans, women, heretics, and even other Christians as being demonic. The libel that Jews used the blood of Christian children to make matzah or that marginalized women entered into Satanic covenants led to millions of deaths.

In his study Europe’s Inner Demons: An Enquiry Inspired by the Great Witch-Hunt, Norman Cohn notes that Christians often imagined a “world purified of all evil” and that “these ancient imaginings are with us still.” As recently as the 1980s, mainstream media was obsessed with a “Satanic panic” about demonic cabals in a manner not dissimilar to QAnon, as scholar David Frankfurter argues here on RD.

One of the themes which I explore in my new book Pandemonium: A Visual History of Demonology is how demonization and dehumanization are equivalent, noting that the “greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was convincing people that they were persecuting him while they gleefully murdered the innocent.” Below are ten images from Pandemonium which chart the ways that such dehumanization has manifested before the modern era.

***

Cernunnos figures, antlered shamanistic priests, are common in the art of Celtic speaking antiquity, such as this example displayed at the National Museum of Denmark. The significance of this image, of which there are around fifty examples dating from the earliest years of the Common Era, remain obscure; yet it was argued until recently (not without controversy) that Cerunnos is the template for the archaic European pan-deity who was latter interpreted by the Christians as a demon, using that as pretext to persecute his worshipers who were subsequently labeled as witches.

***

***

A detail from the fifteenth-century Flemish painter Hieronymus Bosch’s The Temptation of St. Anthony, held at the National Museum of Art in Lisbon, Portugal. A curious detail in the dwarfish figure whose whole body is encompassed by a conical cap that looks like a funnel. The headgear which this demon wears is the conical hat which many Christian princes compelled Jews to wear, so as to differentiate themselves from the wider European community. In his understanding, the demons which assaulted Anthony weren’t just marked as otherworldly—they were marked as Jews. And so this vocabulary of demonization, which has such utility in explaining evil and sorrow, became itself a source of evil and sorrow as Christians used it to justify the violent persecution of Jews and other minorities.

***

***

In his altarpiece for the Austrian church, St. Wolfgang im Salzkammergut, fifteenth-century Italian painter Michael Pacher depicts one of Christ’s temptations in the desert, when the Devil implored the messiah to transform stones into bread. The figure in the painting, with his darker skin tone and curly hair, is marked as ambiguously and ethnically “other.” Such a conflation demonstrates how demonization had profoundly violent effects on marginalized communities as European Christians imagined the Devil as distinctly non-European.

***

***

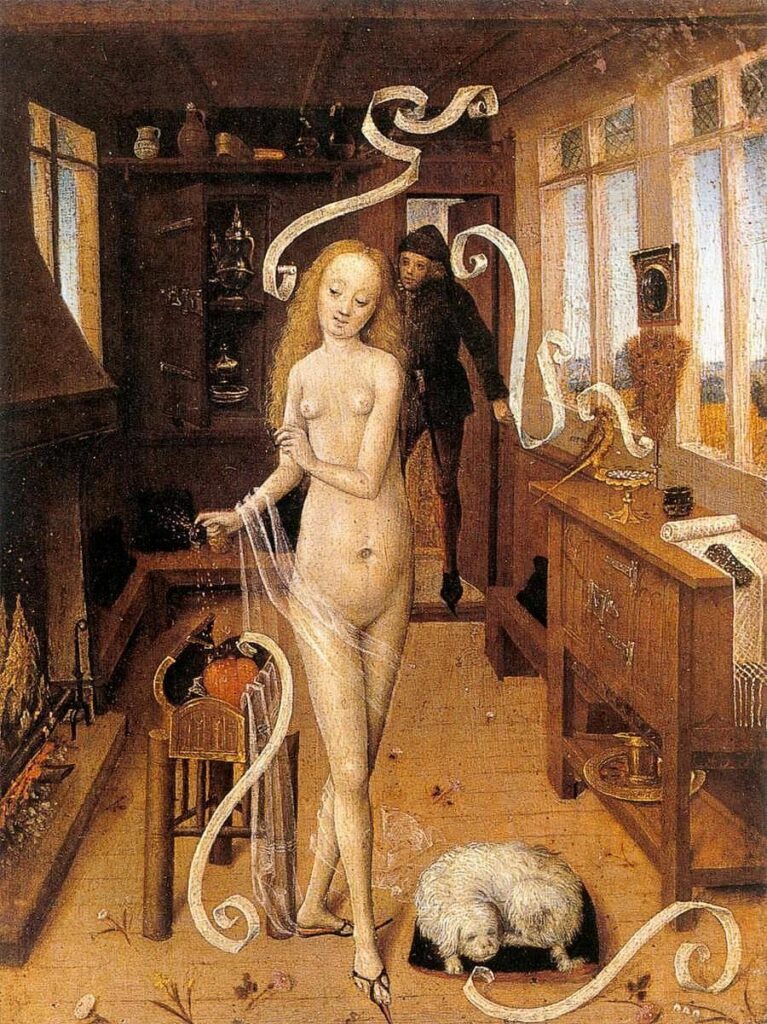

An anonymous fifteenth-century Flemish painting of a young witch having cast a love potion, so as to compel the young man at the door into her bed chamber. The original is held at the Staatliche Museum in Leipzig, Austria. For most of the Middle Ages, to believe in witchcraft was a heresy, for the idea that mere women and men could flout God’s powers through magic was seen as blasphemous, yet ironically by the Renaissance belief in witches (and the subsequent persecutions) became a matter of orthodoxy.

***

***

***

Detail from the Tuscan painter Luca Signorelli’s 1501 fresco Deeds of the Antichrist, housed in Umbria’s Orvieto Cathedral. A nefarious looking Antichrist on the left, unnervingly similar in appearance to Jesus Christ, listens to his whispering father, a horned, rouged, and disturbingly smooth Devil. As Christendom was ripped apart by the convulsions of the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, potential Antichrists were seen everywhere.

***

***

This detail from the German painter Lucas Cranach the Elder’s The Law and the Gospel (1529), housed in the National Gallery in Prague, Czech Republic, illustrates the theological principles which defined the Reformation. Here a figure who believes that his good works alone will guarantee his salvation is surprised to find that his actions alone can’t merit heaven. The cackling green demon pushes the figure into the mouth of hell.

***

***

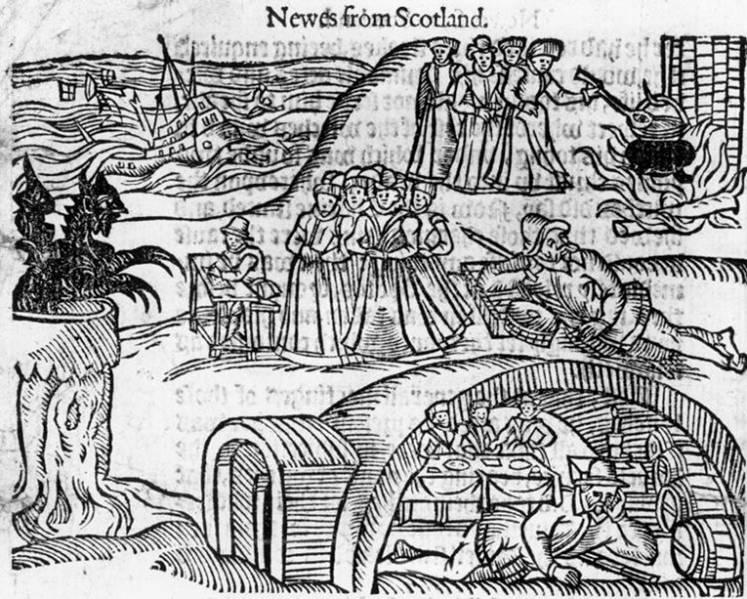

A group of accused witches from the East Lothian region depicted in a 1591 pamphlet entitled News from Scotland, and later featured in King James’ book, with many of the over a hundred women and men who were accused ultimately being executed. In this engraving the witches gather before the Devil.

***

***

Woodcut from an early sixteenth-century German pamphlet depicting Pope Alexander VI, a notorious pontiff from the previous century and member of the corrupt and immoral Spanish Borgia family. Leaving no doubt as to the identity of this deformed and grotesque creature, the caption at the time can be translated from the Latin as “I am the Pope.”

***

***

Not to be outdone, Catholic polemicists responded to Protestant accusations in kind, such as in this front piece to the German pamphleteer Johannes Cochlaeus’ 1529 diatribe The Seven-Headed Luther, which imagines the father of the Reformation as having the same number of heads as the dragon of Revelation, each one symbolizing an aspect of the theologian’s supposed contradictory thought and personality.

***

***

Notorious for the breadth and the extent of his persecutions, the so-called “Witch-Finder General” Matthew Hopkins was responsible for over a hundred executions in the years he was active, taking advantage of the violence and chaos of the English civil wars to use Parliamentary authority in the punishment of suspected witches. This front piece to his 1647 The Discovery of Witches illustrates the supposed role of “familiars,” shapeshifting demonic creatures who attended to witches and took the form of common domestic animals. As is illustrated, familiars could be any variety of creature, from dog, to rabbit, to bull, but the most enduring variety in popular culture is the black cat.

***

***

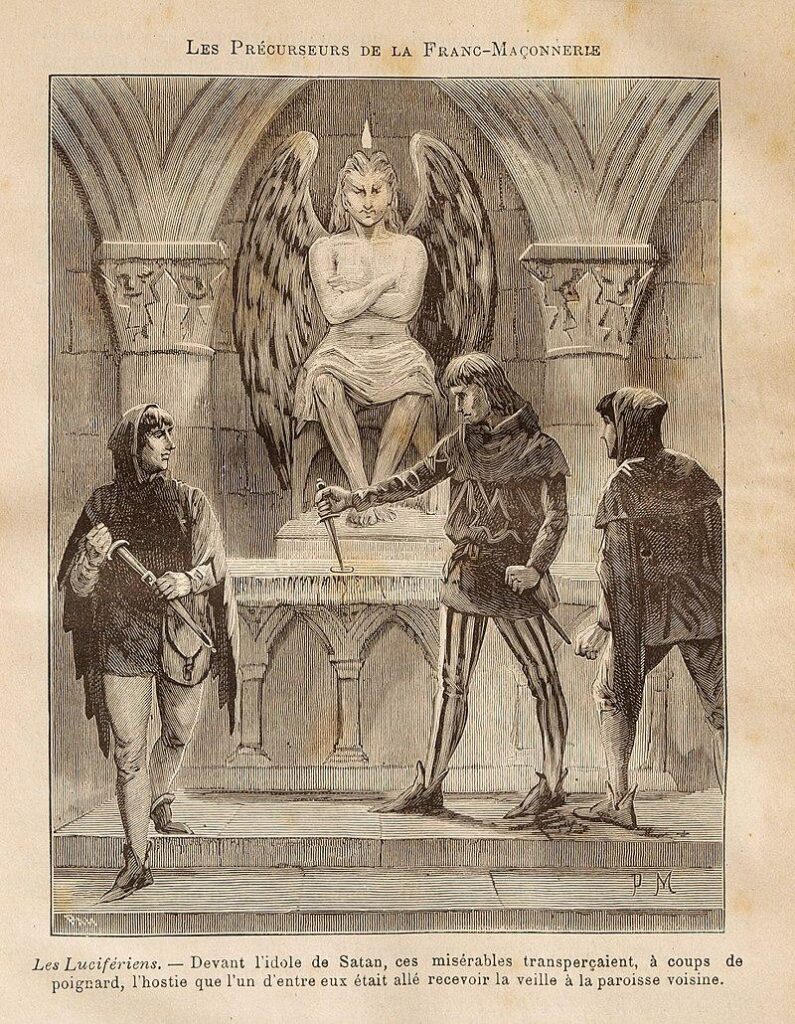

Illustration by Pierre Méjanel showing ritual host desecration, wherein the piercing of the wafer is to literally reenact the crucifixion. This drawing was included in Leo Taxil’s 1886 The Mysteries of Freemasonry, and it should be said that such practices as described therein don’t actually have a corollary in Masonic ritual.

***

***

An 1890 composition by the German painter Franz Stuck entitled Lucifer, now housed at the National Gallery for Foreign Art in Sofia, Bulgaria. His stark, intense, penetrating portrait of God’s adversary presents Lucifer as less a demon than as a man possessed with a singular dark vitality. Such a piece foreshadows the coming alienation, nihilistic individualism, and solipsism of modernism. Incidentally and disturbingly, Stuck was the favorite painter of a young artist named Adolph Hitler.

***