Are the nonreligious a marginalized group in America? When I brought this question up to a friend who lives in New York the other day, he was skeptical. Practically everyone he knows is an atheist, he says, as if this were the most natural thing in the world. As someone who grew up in central Indiana and Colorado Springs, where I was sent to evangelical schools, his attitude both bemused and concerned me. The disconnect just serves to illustrate that how one answers this question may vary wildly depending on where one sits—in some cases quite literally.

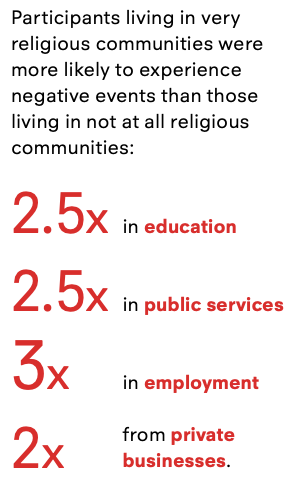

According to a new report from American Atheists* called Reality Check: Being Nonreligious in America, those living in “very religious” communities reported substantially more discrimination in employment, education, and other services than those living in “not at all religious” communities.

Visual from “Reality Check: Being Nonreligious in America,” courtesy of American Atheists.

The Secular Survey, from which the report was drawn, includes data from 33,897 nonreligious Americans—those who self-identify as atheists, agnostics, humanists, skeptics, freethinkers, secular, and/or simply nonreligious. The survey’s designers consider a lack of data on nonreligious Americans an obstacle to effective advocacy for the needs of this group, which the report describes as “an invisible minority.”

In a webinar for journalists and advocates, American Atheists’ vice president for legal and policy, Allison M. Gill, stressed that most data we currently have fail to distinguish between the various stripes of the religiously unaffiliated (i.e. “nones”). Nones may retain some religious beliefs or consider themselves religious without belonging to a formal institution, but this is not true of the nonreligious proper, as the report defines them. As Gill observes, this “can sometimes obfuscate the needs of our community.”

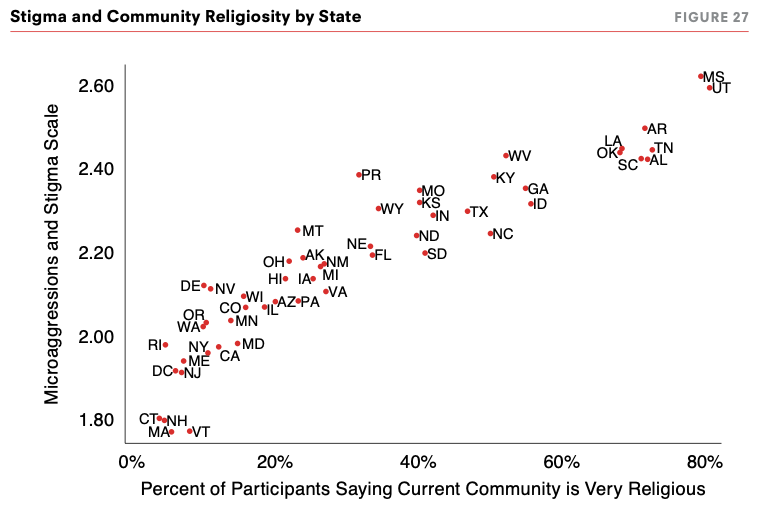

According to Reality Check, “Participants’ analysis of community religiosity aligned well with geographic expectations.” In other words, regions you’d expect to be highly religious were reported by participants to be so. In addition, “While nonreligious beliefs may be casually accepted in states like California and Vermont, nonreligious people living in states like Mississippi and Utah have markedly different experiences.”

“Stigma and Community Religiosity by State” chart is from “Reality Check: Being Nonreligious in America,” courtesy of American Atheists.

Indeed, the 554 survey respondents from Utah rated their state more religious than respondents from any other state, although Mississippians reported a slightly higher degree of stigmatization of nonreligious people. The study measured stigma using a scale based on nine microaggressions targeting nonreligious people, and respondents were asked to note whether and how often they had experienced each one over the year prior to taking the survey. Per the report:

Nearly two thirds of all survey participants were sometimes, frequently, or almost always asked to join in thanking God for a fortunate event (65.6%). Nearly half (47.5%) of survey participants recalled sometimes, frequently, or almost always being asked to or feeling pressure to pretend that they are religious. Nearly half of participants were sometimes, frequently, or almost always asked to go along with religious traditions to avoid stirring up trouble (45.3%), and nearly two in five (37.9%) were treated like they don’t understand the difference between right and wrong.

Of participants, 26.3% reported that sometimes, frequently or almost always “others have rejected, isolated, ignored or avoided me” and 17.3% reported sometimes, frequently, or almost always being excluded from social gatherings and events because of their nonreligious identity. When RD recently spoke with American Atheists’ Gill over the phone, she also noted that her organization and others like it “hear from constituents every day who have complaints about their children facing discrimination and bullying in school, how they’re at risk at work for talking about their beliefs, how they’re not able to access government services.”

Stigmatized minority or bullies without a pulpit?

The representation of nonreligious Americans as a stigmatized minority is bound to be contentious, particularly when the Secular Survey’s respondents—a convenience sample recruited through secular organizations rather than a representative sample—skew so disproportionately white (92.4% vs. a U.S. Census Bureau estimate of 76.5%, including white Hispanic/Latinx) and male (57.8% vs. 49.2%), a profile that inevitably recalls elevatorgate and the racism, misogyny, and alt-right views that have come to characterize far too much of visible movement atheism in recent years.

If one’s primary associations with being nonreligious are people like Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, Bill Maher, and their vocal and all too often abusive fans, it’s only natural to find it absurd and even offensive that such privileged and powerful men could be considered in any sense marginalized. But before we jump to too many conclusions, in addition to recalling the disparate geographic experiences noted above, we should also note that Secular Survey respondents skew disproportionately LGBTQ (23% vs. an estimated 4.5% of American adults as noted in Reality Check). In addition, Reality Check takes care to note disparate outcomes among African-American, Latinx, ex-Muslim, and LGBTQ respondents, the intersections of whose racial, ethnic, sexuality, and gender identities can affect their experiences as nonreligious Americans.

After reading Reality Check, I recently decided to test the waters on how the politically engaged, broadly progressive public might relate to the representation of nonreligious Americans as a stigmatized minority. I did so, as a queer nonreligious American myself, by posting a 24-hour Twitter poll in which I asked respondents, “Can the language of ‘coming out’ properly be used by anyone forced to conceal an aspect of identity, or does it belong only to the LGBTQ community?”

I noted that the question was inspired by the new report on the Secular Survey, which found that many respondents—particularly those in very religious communities—are forced to conceal their nonreligious identity. The Twitter poll results are, of course, unscientific, but the replies were passionate and deeply divided in ways that matter for the kind of public discussion the Secular Survey is intended to spark:

Based on the frequent reactionary behavior coming out of atheist communities and how that fed people directly into the alt right

I am not happy with atheists using "coming out" unless they're also queer.

Atheists as a group have not been good allies to queer people

— Mean Fat Girl- 🏳️🌈💄 (@Artists_Ali) May 6, 2020

It’s not oppression olympics they just aren’t the same thing and y’all can get your own word esp given how hostile the atheist community is to lgbt people

— El (@sooofanxy) May 6, 2020

All forced concealment.

I'd also include survivors of sexual assault, because regardless of the reason, if you have to hide a part of your lived experiences or face violence, rejection, public scorn or humiliation, then you are disclosing a truth that can – and will- hurt you.

— Jillian Onthehudson 🇺🇲🇨🇦🏳️🌈 (@jillianonthehud) May 6, 2020

As an LGBT non-believer with mental health issues, I'm surprised the majority of folks are saying "coming out" should only be used by LGBT people. Depending on where you live and what group of people you know, the stigma against other characteristics can be as strong or stronger.

— Jami (@jamiblakeley108) May 6, 2020

While some respondents insisted that being nonreligious is a choice in a way that one’s experience of one’s gender and sexuality is not—and even some self-identified atheists replied to the effect that they don’t consider their atheism an identity—the fact remains that in many parts of the United States, being recognized as an unbeliever can come with severe social consequences. In addition, although one’s beliefs about the nature of reality should ideally be a matter of conscience, children have no control over the beliefs they’re raised with or the communal norms that surround them.

If we recognize that forced religious conversion is an act of violence, then we should recognize that living in a community where it’s unsafe to disagree with the prevailing religious consensus and to refuse to participate in religious activities is also to experience violence. As a transgender woman and ex-evangelical, these issues are very relatable to me, as they are to many who have left high-control religious groups, and it’s my fervent conviction that they need to be part of our public discourse.

According to Reality Check:

Nearly one third (31.4%) of participants mostly or always concealed their nonreligious identity from members of their immediate family. Nearly half of participants mostly or always concealed their nonreligious identity among people at work (44.3%) and people at school (42.8%).

Family rejection can come into play as well, with the Secular Survey finding that 29.2% of respondents under 25 whose parents were aware of their nonreligious identity had somewhat or very unsupportive parents. By including questions about loneliness and isolation, the survey was able to suggest that such situations result in higher likelihood of depression, and it also showed that lack of family support for nonreligious Americans resulted in lower educational achievement. The report’s prediction of likely depression corresponds well to recent social scientific findings on the psychological harm that comes to people who consider leaving their high-control religious communities but choose to remain.

In addition, some atheists are at risk of physical violence over their lack of religion. Only .8% of survey respondents reported being physically assaulted over their unbelief, although for African-American respondents the number is 2.5%. Meanwhile, 12% of respondents experienced threats of violence, and 2.5% experienced vandalism (14.2% and 3.2%, respectively, for Latinx respondents).

None of these facts make the experience of “coming out” as nonreligious the same as coming out as LGBTQ, but they do nonetheless show that disclosing one’s nonreligious identity can be fraught and risky depending on one’s social environment. While the report itself did not use the language of coming out, its framing is recognizable as that associated with social justice advocacy. The report’s inclusion of intersectional analysis is also particularly noteworthy for an atheist organization, but is unsurprising given the diversity of American Atheists’ national staff and the organization’s willingness to partner with religious organizations to work toward the common good, as the pluralism inherent in democracy demands.

With respect to the terminology of “coming out,” one of the qualitative responses included in Reality Check, identified as coming from a female respondent in Kentucky, reads in part, “Joining an atheist/humanist meetup group helped me have the courage to ‘come out’ with my secular beliefs. Prior to having a social group, I felt alone without a way to overcome judgement from religious family members.” American Atheists’ Utah Director Dan Ellis also recently commented, “When I came out as an atheist, I experienced discrimination from family members,” adding that he “lost friends—even ones who weren’t particularly religious.”

Gill, herself a transgender lesbian, noted in our phone conversation that the Secular Survey’s questions about identity concealment were indeed meant to get at “a coming out experience,” though the survey deliberately did not use that language in order to avoid possible confusion.

Asked whether she thinks the phrase “coming out” belongs only to the LGBTQ community, Gill remarked, “I would vehemently disagree with that; I think it belongs to everybody. And I see a lot of similarities between being nonreligious and being LGBT.” She stressed that this does not mean that the stigma and discrimination faced by nonreligious people and members of the LGBTQ community are the same, but observed that “the process of coming to awareness of one’s identity and beliefs and revealing it to other people and facing possible rejection is similar.”

The use of the terminology of “coming out” outside of LGBTQ experience will likely remain contentious. But the hardships that many nonreligious Americans face for being nonreligious, while distinct from those faced by LGBTQ Americans, are still very real. Christian privilege and supremacism are pervasive in the United States, and much work remains to be done to render them more visible so that, along with white supremacism and patriarchy, we can work more effectively to dismantle them.

*Full disclosure: I am in regular contact with the leadership of American Atheists, and I was slated to speak at the organization’s 2020 convention before it had to be postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.