The annual celebration of Martin Luther King Day started with controversies and misunderstandings of King and his legacy, mostly from conservatives who once despised and later just mistrusted King and his legacy. In the 1960s they had good reason to oppose the civil rights leader, and King had good reason to fire right back at them, as when he responded to Barry Goldwater’s opposition to the 1964 Civil Rights Bill:

On social and economic issues, Mr. Goldwater represented an unrealistic conservatism that was totally out of touch with the realities of the twentieth century. The issue of poverty compelled the attention of all citizens of our country… On the urgent issue of civil rights, Senator Goldwater represented a philosophy that was morally indefensible and socially suicidal. While not himself a racist, Mr. Goldwater articulated a philosophy which gave aid and comfort to the racist. His candidacy and philosophy would serve as an umbrella under which extremists of all stripes would stand.

Conservatives of a later generation had equally good reason to oppose King’s basic political philosophy and his reading of biblical texts to support his social democratic leanings. Even after King had become an icon, he questioned some of the deepest and most basic assumptions of American society, calling unequivocally for a more just distribution of wealth, coming down hard against the war in Vietnam, and consistently invoking a social gospel critique of the workings of power and wealth. King’s dream, long since denuded of its actual social and economic content in the nationally celebratory rhetoric, demanded fundamental and unsettling disruptions in the normal working of the economic body politic.

From this perspective the senators who opposed the proclamation of King Day in the early 1980s had a point. As late as 1983, twenty-two senators (led by Jesse Helms, unsurprisingly, but featuring a list of senators from all over the country) voted against the national holiday declaration, while President Reagan, when asked about King’s ties to communism, said that we would find out for sure in thirty-five years (referring to the time when King’s FBI files could be released). More adept and politically attuned than the conservative senators, however—and despite his personal opposition—Reagan signed the national holiday into law in November of 1983.

Ultimately, since national icons can’t be opposed they must be co-opted. In doing so, they are frequently distorted beyond all recognition. In the case of King, his fundamentally religious message of the requirements of justice have been confused, or perhaps deliberately distorted, by those who have roped him into the rhetoric of “colorblindness,” for example.

Here in Colorado Springs, the annual King day never fails to arouse conservative hijackings of King and his legacy. While the local paper, the Colorado Springs Gazette historically has enlisted King in its daily defense of libertarianism, this year’s editorialist apparently gave up, simply consigning King Day to an apolitical celebration. Yes, we can all dream, and become whatever we want to be, so the day should be for a celebration of anyone’s dreams. “Regardless your politics, your opinions, take a moment today to reflect on the meaning of having a dream and fulfilling it.” A message conveniently timed for the opening of the new season of American Idol.

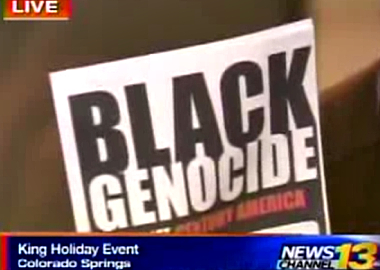

But if the local libertarian right threw up its hands this year, the anti-abortion right continues to draft King into their cause. The Rocky Mountains March 4 Life celebrated King Day by marching to the former home of Planned Parenthood on the west side of Colorado Springs (the facility has since moved, but both the old and new locations are in predominantly white parts of the city), part of a protest against what they believe is a black genocide by abortion. The march, said organizers, upheld “King’s commitment to civil rights for all, which King would agree includes the unborn.” The Rev. Bill Carmody, director of the local Catholic diocese’s Respect for Life Office, said that “we are tying the civil rights movement of Martin Luther King to the civil rights of the pre-born.”

Given the same Catholic diocese’s bitter opposition to last year’s health care reform, it would appear that the “civil rights of the pre-born” stop before the child leaves the womb, at which point, as Martin Luther King pointed out, they might, given class or racial barriers from birth, very well be left without a bootstrap to pull themselves up by.

King’s niece, Alveda King, who appeared at last year’s Glenn Beck rally on the anniversary of the March on Washington, has endorsed the use of her uncle’s name, insisting that today he would be called a “social conservative.” In fact, King strongly supported Planned Parenthood and was awarded the Margaret Sanger Award in 1966.

King’s thoughts on war, peace, justice, community, civil rights, and religion sound quite unlike those who quote him today but opposed him then (or would have if they were alive). The struggle continues to keep King’s drive for economic justice alive, beyond just “civil rights.”

We have some good places to start to reflect on that struggle. Albert Raboteau reminds us of the ancient Christian traditions that feed King’s emphasis on the poor and disfranchised. Historian Barbara Ransby explains King’s “brilliantly imaginative vision of a different, more just and humane world,” and the real-life relentless harassment and persecution to which he was subject through his last years. In RD, Andrew Murphy articulates the difference of the right’s celebration of “tradition” versus the searching self-critiques of King’s speeches, and the necessity of a political movement to turn King’s words into reality.

The historical co-opting of King as icon is inevitable, but it can be resisted through insisting on the central themes of King’s life and legacy. That requires not only the rules of a radical—getting to the root of injustice—but also demanding historical accountability for those who would distort his dream.