Last August, a photo of a grieving father holding a child who had not survived the dangerous passage from Syria to Europe elicited widespread compassion from Americans. But following the Paris attacks on November 13, 2015, Governor Chris Christie and Dr. Ben Carson, Republican candidates for president, put a new face on the Syrian immigrant.

Tapping into American anxiety about admitting to the US individuals who, notwithstanding their seeming innocence, are potential terrorists, Christie proclaimed that “even three-year old orphans” must be denied entry. Carson opined that, just as parents protect their children from “a rabid dog running around your neighborhood,” so also must Americans guard against a potentially lethal contagion of Syrian immigrants. When the House of Representatives subsequently voted in veto-proof numbers to effectively close US borders to Syrian immigrants, Christie and Carson’s fears were enshrined in the political mainstream.

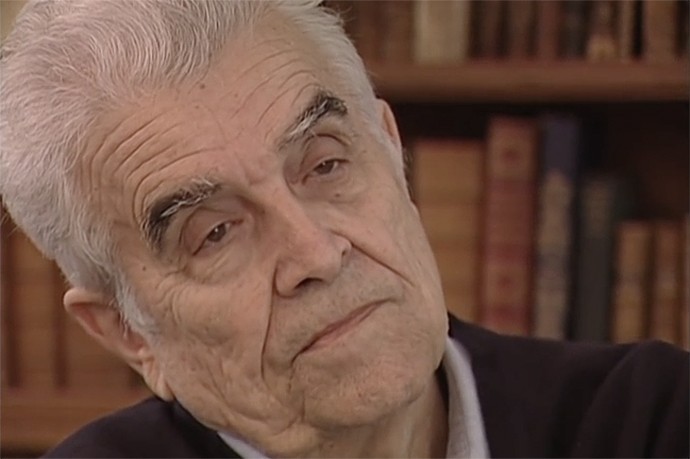

Days before the Paris attacks, on November 4, 2015, René Girard died in Palo Alto, CA at age 91. In the wake of ISIS panic that ensued after the attacks, Girard’s legacy –a lifetime of writing on violence, religion, and the human condition—has never seemed more vital. After all, Girard writes in The Scapegoat that, “Each person must ask what his relationship is to the scapegoat. I am not aware of my own, and I am persuaded that the same holds true for my readers. We only have legitimate enmities. And yet the entire universe swarms with scapegoats.”

Little wonder that Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, who draws on Girard’s insights in his recently published Not in God’s Name: Confronting Religious Violence, stated in a recent interview that “the two people who have had the most profound insight in the 20th century were Sigmund Freud and René Girard.”

Newspaper obituaries in France, Britain, Germany, Austria, Italy, and Spain acknowledged as much; and, in the country of Girard’s birth, French president François Hollande eulogized Girard as a “passionate intellectual” whose ideas now “mark the history of thought.”

Girard’s profound impact on multiple fields is such that, upon his election to the Académie Française in 2005, he was hailed as “The Darwin of the Human Sciences” by fellow honoree Michel Serres. Girard’s career included many honors: two Guggenheim Fellowships, a lifetime achievement award from the Modern Language Association, and the Order of Isabella the Catholic, awarded to him by Spain’s King Juan Carlos of Spain. Girard’s teaching appointments, which included Duke University, Bryn Mawr College, Johns Hopkins University and the State University of New York at Buffalo, culminated in his 1981 appointment as the Andrew B. Hammond Professor of French Language, Literature, and civilization at Stanford University, where he remained until his retirement in 1995.

Yet Girard always was a controversial figure, in large part because his major contributions to thought—a theory of mimetic desire and the scapegoat mechanism—were offered in the style of grand theory and accorded special significance to the Christian Gospels. Out-of-sync in the 1980s and 90s with rising currents of post-structuralism and deconstruction as well as with emerging critiques, even among theologians, of Christian exceptionalism, Girard’s thought was, in ironic testimony to first principles of mimetic theory, simultaneously attractive and repelling.

Girard laid the foundations for his theory with his first book, Deceit, Desire, and the Novel. Arguing that literature is reflective and revelatory of human experience, Girard also claims that literature can transform human experience. Authors of great literature do not mask the truth of human experience, serving up “romantic” (romantique) illusions; rather they pen “novelistic” (romanesque) works that elucidate human circumstances: Offering models to be imitated, these authors reveal a different existence in which “deception gives way to truth, anguish to remembrance, agitation to repose, and hatred to love.”

Acclaiming Girard’s approach to literature, Eugene Webb places Girard in a lineage of “morally serious literary critics” inclusive of Dante, Samuel Johnson, and Sartre. Observing lessons in “moral truth” in literature, these thinkers turned to literature “not just for the sake of purely intellectual or aesthetic satisfaction but in order to find a way to deal with these problems in practice.” That Girard was committed to “problems in practice” enabled him to make his mark not only on the study of literature but also on the study of religion. Indeed, if the theory of mimetic desire emerged from Girard’s explorations of the novel, the theory achieved its greatest realization in his reflections on religion, in books such as Violence and the Sacred, Things Hidden since the Foundation of the World, and The Scapegoat.

Religion, according to many, gives rise to violence. But for Girard, mimetic desire and surrogate victimization, emerging over the long course of evolutionary development, attest to the origins in violence of human society and all cultural institutions, including religion. Only on a superficial level is mimetic desire oriented toward having things that another has or seeks to acquire. On a deeper level, desire arises in humans because we lack being. Each of us look to another to inform us of what we should desire in order to be; however, each of us finds our attention drawn not toward the object that the other recommends but toward the other who must surely be capable of conferring an even greater plentitude of being: “Imitative desire is always a desire to be another.”

We discover that the closer we come to acquiring the object of our models’ desires and, through that acquisition, to our models, the greater the rejection or refusal directed toward us by our models. As a consequence, in the grip of desire, humans are vulnerable to acquisitive rivalry that devolves into violence. Veneration and rejection structure our experience until, in a shocking denouement of the dynamics of rivalry that sees difference between each of us and our models obliterated by a single, common desire, our models become monstrous doubles by whom we are as much repulsed as we earlier were attracted. Desire now precipitates a mimetic crisis.

Fraternal conflicts in myth and history—Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau, Eteocles and Polyneices, Romulus and Remus—show that mimetic tensions presage widespread upheaval. Groups of persons display symptoms of discord—economic, social, and political—that are crisscrossed by multiplying trajectories of mimetic conflict. These clashes coalesce and reinforce each other until a mob, in the throes of a mimetic free-for-all, directs its violence toward a single, arbitrarily chosen victim. With aggression displaced onto this scapegoat, a single entity now serves as a substitute for the many who condemn it. But in death, the scapegoat also is an object of veneration.

Violence, passed through and among a community, has centered on a victim and been transformed. For a time, that community will be at peace. As Robert Hamerton-Kelly describes the mechanism: “It leaves as violence and returns as hominization, religion, and culture.” Rituals are central to this process because they enable societies to replicate in a controlled environment the violence that first gave rise to human community and now sustains it. Myths record the reconciling work of the scapegoat—presenting the victim as the passive instrument of its own transformation. Law also marks the site of sacrifice. Other markers typically are suppressed; thus, the only remaining testimony to culture-creating violence is contamination and pollution that seep out of the Law.

For over three decades, scholars of religion have drawn on Girard to inform their work. Christian theologians and New Testament scholars have found Girard’s insights on the scapegoat mechanism of special salience. Girard has argued that myths attest to the scapegoat mechanism from the perspective of persecutors: the victim of mob violence is guilty. By contrast, the Gospels break with myth to present the victim as innocent. Living at a time of social crisis, Jesus is the victim of mob action; but his innocence, attested to by the Gospels, breaks apart the scapegoat mechanism, forever shaking the foundations of a culture built on sacrifice. Even scholars who disagree with Girard about his insights attest to his influence on their work; as a consequence, Girard has had a pervasive impact, especially on scholars who want to understand the dynamics of ritual, the meaning of myth, the origins and history of violence, and the relationship between violence and religion.

What will be Girard’s legacy? In 1981, Girard responded to early criticism of his work, stating, “Theories are expendable. They should be criticized. When people tell me my work is too systematic, I say, ‘I make it as systematic as possible for you to be able to prove it wrong.’” Girard followed his own advice. In correspondence over a decade with theologian Raymund Schwager, Girard altered his views on the New Testament, reframing his perspective on vestiges of archaic religion in the text and modifying his views on its revelatory exposure of the scapegoat mechanism.

Similarly, Girard’s conversations with Judaic studies scholar Sandor Goodhart, who argues that the Hebrew Bible uncovers the scapegoat mechanism, led Girard to reassess Christian exceptionalism in his work. Girard transitioned from acknowledging in an essay in Violence Renounced (2002) that the Hebrew Bible contains anti-scapegoating currents that nevertheless require the Gospels for full realization to claiming in Evolution and Conversion (2007) that the exposure of the scapegoat mechanism in the Hebrew Bible (e.g., the Joseph story) is “seen again in the Passion of Christ.”

In Sacrifice, one of his last books, Girard moves outside the orbit of Western religion to observe in the Hindu Vedas an eclipse of the sacrificial logic governing human culture that uncovers its mechanism in ways comparable though not identical to that disclosure in the sacred texts of Judaism and Christianity.

Students of mimetic theory have followed Girard’s own example in pursuing a critical engagement with his theory. In recent years, scholarship grounded in mimetic theory has explored the world religions in new ways. International research teams have investigated the implications of mimetic theory for neuroscience, evolutionary biology, archeology, and cognitive psychology. Responding to early criticisms of mimetic theory by feminist scholars Toril Moi and Sarah Kofman, feminist scholars have engaged in a constructive appropriation of mimetic theory, exploring gendered violence even as they have given new attention to how embodiment shapes mimetic conflict. Other scholars have drawn on Girard in their study of the African American experience, from slavery to the present. Girard’s thought also is informing analyses of threats posed to the environment by global warming.

Even so, Girard’s legacy hangs in the balance. Girard called for an engaged scholarship capable of addressing problems in practice; however, in Battling to the End, his last major work, Girard takes a grim view of humanity’s capacity to avert a world-ending apocalypse. He asserts that “violence is a terrible adversary, especially since it always wins.”

Already in The Scapegoat, Girard points out risks that attend the end of sacrifice in the modern world. With the scapegoat mechanism exposed, humans lose their capacity to limit violence as they did in the past because they no longer can effectively exchange unrestrained mutual slaughter for a focused attack on a scapegoat. As a consequence, humanity risks escalating violent mimesis from which no escape is possible. But The Scapegoat ends on a note of qualified hope. If we forgive one another, we still can avert cataclysmic violence. In Battling to the End, confronting the utter “powerlessness of politics against the escalation of extremes,” Girard doubts that humans can step back from the brink. As we reflect on these contrasting visions, the words of Martin Luther King, Jr. are especially apt: “The choice is not between violence and nonviolence but between nonviolence and nonexistence.”

Girard asked others to challenge rather than dismiss his theory. In a world caught up in a sacrificial logic that portends mutual destruction, more than ever, Girard would want us bring our best critical insights to bear on his provocative and unsettling body of work.