No matter what unpredictable antics and wild outfits might be in store for audiences on the night of music awards shows, one can reliably bet that at least one acceptance speech will start with, “First of all, I want to thank God.” So when it came time for Kendrick Lamar to accept the 2016 Grammy for Best Rap Album, it was no surprise that he began, “First off, all glory to God, that’s for sure.” This tradition has often been fodder for comedians remarking that these are empty gestures and that, of all requests sent to God, an artist winning a Grammy is likely low on the list of priorities.

But this year the wisecracking set were largely silent on the issue, as Kendrick Lamar has demonstrated his Christian credentials time and again in his music and public declarations. In a thoughtful BuzzFeed essay on Lamar’s Christianity, Reggie Ugwu describes the rapper’s narrative style as employing “a fondness for using songs as parables, in which the horror of violence and rote debasement of humanity can only be tempered by the grace that comes from a higher power.” The public declarations of faith that were once anathema to audiences have resonated deeply with the public, but he is just one of an emerging group of mainstream artists conjuring the holy to explain the shape of struggle and love in the world as they experience it.

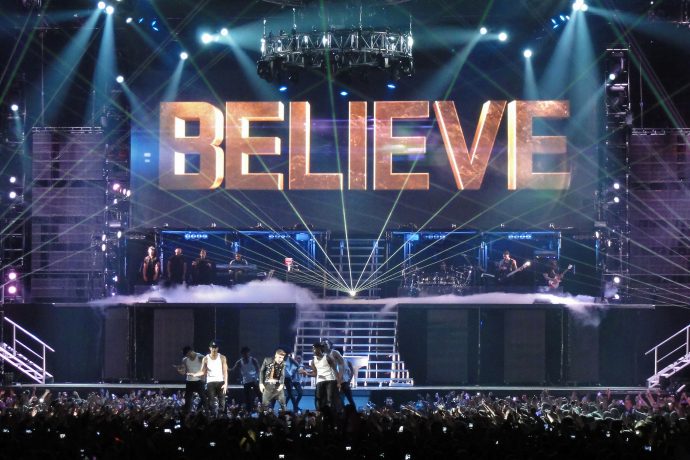

Soon after the release of a Justin Bieber profile in Complex last year the internet exploded in mockery at a quote that emerged from the interview: “Like I said, you don’t need to go to church to be a Christian. If you go to Taco Bell, that doesn’t make you a taco.” Bieber detractors are quick to pounce on such low-hanging fruit as evidence of his dimwittedness. What was missed by audiences so eager for a punch line was a young man’s thoughtful, theologically robust contemplations of faith. He said:

What Jesus did when he came to the cross was basically say, “You don’t have to feel any of that stuff.” We could take out all of our insecurities, we could take away all of the hurt, all the pain, all the fear, all the trauma. That doesn’t need to be there. So all this healing that you’re trying to do, it’s unnecessary. We have the greatest healer of all and his name is Jesus Christ. And he really heals. This is it. It’s time that we all share our voice. Whatever you believe. Share it. I’m at a point where I’m not going to hold this in.

This is not the decorative Christianity of a cross-wearing boy band member or the God-thanking pop star at the VMA podium—or even the theological hollowness of Creed’s frontman spreading his arms wide to ostensibly invite Jesus in. This is a devout man declaring the salvific dimensions of the cross. But perhaps the most telling revelation was when he said, “I’m not religious. I, personally, love Jesus and that was my salvation.”

That these two diametrically opposed statements came out of Bieber’s mouth one after the other could again be fodder for mockery to his detractors. Finding salvation in Jesus is the definition of being a Christian and Christianity is, for better or worse, a religion. Bieber is also a notable member of Hillsong NYC, the SoHo House equivalent of Christian congregations in the city. Why then, does he insist against identifying as religious?

To a generation brought up in the aftershocks of the Moral Majority and no strong public religious figures that didn’t come armed with brutal social agendas, “religion” and “organized, politicized religion” have become synonymous. For younger generations faith hasn’t disappeared so much as it’s migrated to the cultural region of popular music and away from the community-focused cultural region of the institutional church.

But both mainliners and evangelicals panicking over the rise of young people unaffiliated with a church have been looking for the youth in the wrong places and asking them the wrong questions when they do find them. They’ve been so preoccupied with churches bearing steeples and bells that they’ve failed to see the ways popular music is in conversation, and occasional wrestling matches, with the holy. Christianity, and a very orthodox Christianity at that, is hiding in plain sight. The last decade has seen a marked rise in mainstream musicians delivering explicit Christian messages, both in their lyrics and in their personal professions of faith.

In the second decade of the new millennium, religious music has taken on a level of sophistication once reserved exclusively for the conflicted devout. Just ten years ago this wasn’t so. The George W. Bush administration, in which millennials came of age, was reigned over by a simple, angry deity who made one-dimensional characterizations of God more readily available than complex ones. The God-Rock genre had a decent run in the 1990s and early aughts, but its contents lacked theological rigor. More wholesome bands like Jars of Clay essentially sang praise anthems while an angstier West Coast nouveau evangelical ethos emerged in bands like P.O.D.

On the other side of this spectrum were bands that positioned themselves as anti-Christian, though even their blasphemies came up short. Marilyn Manson scared the daylights out of children and parents alike in his 1990s heyday, but his most controversial album, Antichrist Superstar, was little more than a play on words of a harmless and beloved musical. Even the reliably contrarian Slayer could come up with an album title no more nuanced or threatening to the establishment than God Hates Us All for their early twenty-first century release. It was a time of ordinary gods fighting ordinary devils.

This was true at least of mainline denominations and white evangelicals. Though they were not without their own conflicts, black churches were largely spared the generational ruptures that cast Christian-raised white Americans into the “None” category. Because rap never divested from its origins in the prophetic witness of the black church, it’s not surprising that rap and hip hop have been the home base for some of the most explicitly Christian content in music for some time. As is often the case, Kanye West was leaps and bounds ahead of his time when he released “Jesus Walks” on 2004’s The College Dropout:

God show me the way because the Devil’s tryin’ to break me down (Jesus Walks with me)/The only thing that I pray is that my feet don’t fail me now (I want Jesus)/(Jesus Walks) And I don’t think there is nothing I can do now to right my wrongs (Jesus Walks with me)/I want to talk to God, but I’m afraid because we ain’t spoke in so long.

This desperate cry to the heavens comes from a prodigal son beset by evil and temptation seeking the guidance of God. West has never shied away from sharing his faith publicly, but the public’s inclination to identify all of his declarations as art projects and gimmicks has prevented him from being taken seriously as a Christian artist.

But breakout stars like fellow Chicagoan Chance the Rapper have taken notice and made more explicitly Christian music than the genre has ever seen in the mainstream. Chance makes direct appeals to God and Jesus on tracks and at his concerts that have come to double as revivals for a splendid faith rooted in communal love and kingdom living. “I speak to God in public/He keep my rhymes in couplets/He think the new shit jam, I think we mutual fans,” Chance declares, making kinship bonds with God and fearlessly addressing him under the sometimes unforgiving eyes of a public that insists that its church and art remain separate.

“There’s a boldness here, a kind of chutzpah, that might challenge popular conceptions of piety, but Chance’s faith in a God who accepts every emotion and welcomes every form of candor and good humor is every bit biblical,” writes David Dark at MTV. What has surprised many is how open audiences. But audiences are receptive to Chance’s message in a way that might have been resisted earlier this century, during the reign of that more violent and simple god. This was evident in the treatment of the few Christian music success stories gaining critical acclaim.

Two notable exceptions to the “No Gods Allowed’ rule in indie music were Neutral Milk Hotel and Sufjan Stevens, both outwardly and explicitly religious in much of their lyrical content. Critics dutifully labored to remove Christ’s centrality from their music in their reviews, trying to paint more ambiguity into the lyrics than was present in order to explain away how it could possibly resonate. The Rolling Stone review of Neutral Milk Hotel’s In The Aeroplane Over the Sea says, “his lyrics carry the innocent piety of the early Beats, with semireligious visions and a pre-electronic-age feel: medicines, Sunday shoes, holy rattlesnakes and the… king of carrot flowers.” The review conveniently skips over lyrics referring to holy water, miracles, and everlasting life, which defy categorizations like “innocent piety.”

The Pitchfork review of the album is more flattering but describes it lyrically as “a world of cannibalism, elastic sexuality and freaks of nature” rather than recognizing those elements as sacramental, devotional, and transfigured. Neither review makes mention of whole, explicit verses like, “And when we break we’ll wait for our miracle/God is a place where some holy spectacle lies/When we break we’ll wait for our miracle/God is a place you will wait for the rest of your life,” or declarative introductions like, “I love you Jesus Christ/Jesus Christ, I love you, yes I do.”

Sufjan Stevens’ religious overtones have often been similarly washed from the critical record. A 2004 Pitchfork review of Stevens’ most explicitly Christian album, Seven Swans, claims, “On songs like ‘All the Trees of the Field Will Clap Their Hands’ and ‘To Be Alone with You’, Sufjan does well to collapse the distinction between divine- and human-directed affections—his ‘You’ could apply to God and loved one alike.”

The former song’s title is a direct pull from the Book of Isaiah which reads in full, “For you will go out with joy/And be led forth with peace; The mountains and the hills will break forth into shouts of joy before you/And all the trees of the field will clap their hands.” The latter song features lyrics such as “You gave your body to the lonely/They took your clothes/You gave up a wife and a family/You gave your ghost,” which certainly sounds awfully close to the sacrifices of Jesus. And if that were not enough evidence, the concluding stanza contains the line, “To be alone with me and went up on the tree.” Now, it’s not impossible that Stevens is referring to a regular old meeting between two friends in a regular old tree as having profound personal significance. But if you swing Occam’s Razor in the direction of that song, you’re going to slam right into the cross.

The critic concludes, “Seven Swans partly succeeds for me because Sufjan rarely steps foot in the excess of pedantic preaching, despite the openly Christian nature of his lyrics here.” The cognitive dissonance required to listen to an album in which play-by-plays of the Transfiguration of Jesus and the Binding of Isaac are thoroughly detailed and not declare it either pedantic or preachy is a deep dissonance indeed. Sufjan Stevens plays like, seven hundred instruments. He composes for ballets. The dude likes his details. Why couldn’t critics just let Sufjan Stevens bear prophetic witness?

Perhaps it’s that the aftertaste of the aforementioned politicized religious right is still too bitter to consider that there was something salvageable beneath the hateful rhetoric. Or perhaps to admit being moved by explicitly Christian music—not despite its Christian themes, but precisely because of them—is too much to bear for a generation that’s crafted an identity around its alleged immunity to grace.

Stevens stands out as one of the most explicitly Christian artists of the century but he is hardly alone in grappling with the holy for mostly secular audiences. One of the most notable has been break-out star Julien Baker, a Memphis-born singer-songwriter whose debut album Sprained Ankle is receiving almost universal praise. “God is my favourite topic. But I’m never at the merch table like, ‘Have you heard the Good News of our Lord and saviour Jesus Christ?’ I would never hit someone with that. I feel that is way too heavy-handed and does a bit more harm than good,” she tells CBC Music. “I don’t consider myself a Christian artist,” she concludes, in the self-contradicting tradition of Bieber.

But where musically Bieber professes his faith in opaque gestures, like naming his album “Purpose” and alluding to an elevated kind of forgiveness, Baker is explicit. “Baker engages with her reaffirmed faith in ‘Rejoice,’ a soaring three-minute ode to belief that has become the climax of her live set, and which she calls her ‘mission statement, if I have one,’” writes Rachel Syme in a recent New Yorker profile. On the track, Baker declares, “But I think there’s a god and he hears either way when I rejoice and complain/Lift my voice that I was made/And somebody’s listening at night with the ghosts of my friends when I pray.” This God is not an amorphous therapeutic deity of yesteryear nor a mostly ornamental cross in a photo shoot. This is the living Lord who hears our prayers.

But these ultra-devout performers share a peculiar space with a number of other artists whose personal faiths are inconsequential to their public personae but whose fluency in the holy plays out in, well, mysterious ways. Lana Del Rey’s catalogue runs deep with both religious imagery and sentiment; waves of apostasy crash over moments of divine revelation and then reverse course back into faith again. She may have claimed “God’s dead…[and] baby, that’s alright with me” on the track “Gods and Monsters,” but a declaration of death is just a roundabout way of affirming existence.

On her most recent album, Honeymoon, she slowly unleashes a litany of appeals she has made to that same God, “God knows I live/God knows I died/God knows I begged/Begged, borrowed and cried/God knows I loved/God knows I lied/God knows I lost/God gave me life/And God knows I tried.” A few tracks later, on “Religion,” she moans, “When I’m down on my knees, you’re how I pray/Hallelujah, I need your love/Hallelujah, I need your love.” It turns out that to be witnessed by God but inadequately redeemed can turn a woman searching for other objects of worship.

In a similar vein, Hozier’s blasphemous heartsick anthem “Take Me To Church” has captured the public’s ear, having been streamed on Spotify more than half a billion times. “She tells me ‘worship in the bedroom’/The only heaven/I’ll be sent to/Is when I’m alone with you/I was born sick, but I love it/Command me to be well/Amen. Amen. Amen,” he sings to a lover, worshiping her as he might a god. This is the language of blasphemy and of a kind that still acknowledges the sin at its core as a force in the world, even as it challenges the notions of it.

St. Vincent (a.k.a. Annie Clark) kicked off her career in a similar fashion, with the cheekily titled, “Jesus Saves, I Spend,” which deceptively covers a meditation on her aching devotion to a lover: “Come my love the stage is waiting/Be the one to save my saving grace/While Jesus is saving I’m spending all my grace/On rosy-red pallor of lights on center stage.” On 2014’s “I Prefer Your Love To Jesus,” Clark reserves her ultimate love for her mother, whom she asks for forgiveness instead of any divine redeemer. “But all the good in me is because of you/It’s true,” she sings with the loud silence of omission of any mention of the God alleged to be the source of goodness. She defies God by leaving him out of her conclusion at all. But this is the silent treatment toward God rather than a denial of his existence. It calls God to task by not appealing to God at all.

An implicit acknowledgment is present across this diverse range of musical output that that which is holy is also whole. With the authority of the church largely removed from the lives of young people, institutional religion is no longer mediating theological conversations. This has given artists and audiences free rein to reach more deeply into their Christian heritages and memories to grapple with holy mysteries that were once closely managed by the church.

The resulting shift means that artists are more likely to resist the concept of grace than the concept of sin: their defiance of the holy is not in the tone of repentant fear so much as a kind of performative dismissal of the possibility that they too are beloved. They do not fear Hell so much as they wonder if they’ll like Heaven. But the absence of the church as an institution means that these reflections occur largely in a scattered diaspora of the faithful or inquiring imagination; there is no community through which to engage these meditations or give them a name.With more messages about God coming to young people from their playlists than ever before, the institutional church loses even more of its centrality as the arbiter of Christian theological conversation. While some may mourn what they see as the death of the church’s influences, others might recognize the transformation of the message into something bigger than its previous incarnation and rejoice at the proof that the divine is too big to be held hostage within the walls of the church.

Julien Baker told The New Yorker, “‘Ultimately, I feel like there is just a pervasive evidence of God… Though I know that is maybe a controversial thing to say.” A survey of the musical landscape suggests otherwise. Though Baker and other artists are reluctant to identify as Christian artists or explicitly state their religious influences, the fingerprints of the Gospels on their works is undeniable. These are not the vague spiritual notions to which public figures are expected to nod in what some hold-outs insist is a Christian nation, they are radical truth claims about miracles, redemption, and the creator.

Whether in embrace or rejection, the language of the divine in popular music indicates an unleashing of Christian imagination that only the decline of the church could facilitate. Artists are free to identify as they please, but denying that they are Christian artists when their bodies and speech run thick with the Good News is every bit as believable as a human calling himself a taco just because he’s in a Taco Bell.