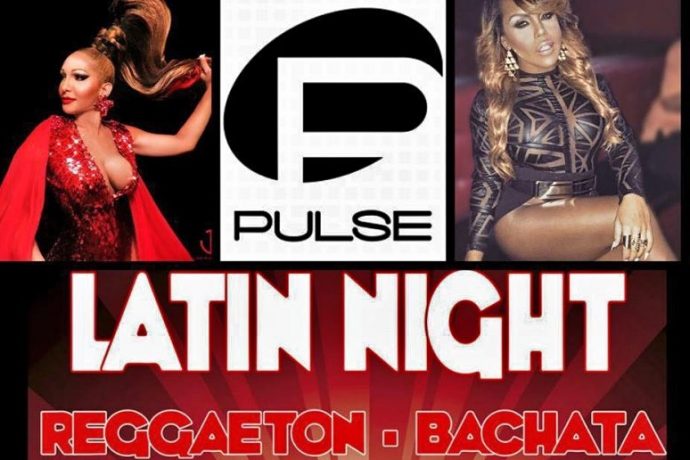

“Oh my God, it was Latin Night,” I said to myself as I lay in bed on Sunday morning, reading the news about the Orlando shooting on my phone.

In the wake of the tragedy, I have found myself mostly at a loss for words, stuttering between anger and sadness. I can not fully describe what I was feeling and thinking that morning as I was getting ready to head over to the LA Pride parade—even as news came in of an arrest in Santa Monica, earlier in the day, of a heavily armed man who was supposedly en route to the Pride event in West Hollywood.

As I watched the Los Angeles SWAT team and armored vehicles cruising up and down the LA Pride parade route a couple hours later, my heart broke and my body ached. I walked along the route and saw the same anti-gay protestors who show up every year. Yesterday, they were behind two sets of barriers with a squad of SWAT officers next to them. And as I stood across from them, listening to their loud condemnations, I felt worried. Not for myself. Not even for them. But for the spirit of our community.

Headlines continued to flash buzzwords—“terrorism,” “ISIS,” “hate crime”—but the truth is, we really don’t have language to talk about these events. We don’t have the right words to ask the questions that need to be asked right now.

As I watched the parade, I saw the float for the Los Angeles LGBT Center approaching. Behind their banner were large letters spelling out, “ORLANDO.” On their float, performing, was Mariachi Arcoiris de Los Ángeles, the world’s first and only LGBTQ mariachi band. I made eye contact with Natalia Melendez as she sang, “Cucurrucucú Paloma,” a Mexican huapango-style song about love, loss, and pain. Tears began to pour down my face and I said to myself: “My people…”

As a theologian, I may not have the words to make sense of these events right now, but I do have the vocabulary to talk about what these spaces mean to queer Latin@s, like myself.

An elementary school, a church, a synagogue, a mosque, a gay nightclub: what these spaces have in common is that they are presumed to be safe spaces for the people within. As a queer theologian, I understand why we are so quick to name gay nightclubs as sanctuaries and sacred spaces, but as a Latino theologian, I urge us to pause and talk about the fact that the attack occurred on Pulse’s “Latin Night.” Let us own that communities of color are mourning the loss of our brown and black kin.

When I came out as gay, I found community and safety in Latin@ queer spaces. Through the rhythmic sounds of cumbia, merengue, reggaeton, and hip-hop that roused the core of my inner brown being, I found a space where I could dance through the traumatic history of growing up as femme brown boy, isolated in the borderlands between being called “joto” and “maricón” on one end and living in a white man’s world on the other. It was through Latin@ queer spaces that I came into my own critical understanding of my embodied reality—living at the intersections of racial and sexual minority.

These experiences became a springboard for critical engagement as I began to develop a theological vocabulary to describe what happens in those spaces. I learned to love myself. I learned to be a healer in my community.

Surely, gay nightclubs become religious spaces amidst the communitas of queer bodies inhabiting space together in kinship, but our people, Latin@s and Latin Americans, have a long history of creating ceremonial centers when our own homes became violent landscapes.

And just so, Latin@ queer spaces were always spaces of healing—migratory spaces we journeyed to, to be in solidarity with one another in our shared pain and suffering, but also in our shared joy and triumph.

We anointed one another with affirmation and laughter. We created fellowship and communion—because too many of us had traversed dangerous landscapes just to get there in the first place. The Spirit lived and carried through each and every one of us. We emerged from the shadows we worshipped in to survive and to be storytellers about our journeys. These are our sacred spaces.

I watch the media tripping over how to describe this tragedy, anxiously going back and forth between “terrorism” and “hate crime.” (When many of us know, all too well, that it is “terrorism” when the victims are white Americans—otherwise it’s simply a “hate crime.” But, then again, it can only be a hate crime if the perpetrators are white Americans, otherwise it’s “terrorism.”)

Somehow the story is more easily told when we don’t have to talk about race—because no one knows how to talk about when people of color attack other people of color. But when reports refer to an attack on a “gay nightclub,” the truth about the violence that happens to queer and trans people of color is avoided.

When thinking about the theological significance of these spaces for queer people, to not talk about racial experience is to fold black and brown bodies into a history we have been consistently been excluded from. And more than that, these are our ceremonial centers. These are our places of worship.

To not talk about the fact that this occurred during “Latin Night” is to deny the necessity of queer of color spaces. It is to deny queer of color magic. When queer of color spaces have been reduced to “special nights” to be celebrated in white-dominated spaces, we have to the name that sacred geography. Because for many of us, these are the only spaces our community has where we can heal our hurts.

I caution the mainstream media to not misappropriate our anger and sadness as anti-religious or Islamophobic. We are mourning an attack on the sanctity of our community. We are in pain as we have lost our fellow healers.

The warriors and healers of our past and present are with us as we march forward in pursuit of whatever it is that defines our new home at the end of this painful journey. We have lost mythical heroes in this tragedy. We have lost 50 healers: who look like us, who speak Spanish like us, who have an accent like us, who are femme like us, who are butch like us, who call their mothers every day, who have complicated relationships with their fathers, and so on. And it hurts.

Several years back, when I received the heart-wrenching news of the passing of queer Latino theorist, José Esteban Muñoz, I was unsettled by the loss of someone else who wrote about our experiences as a queer Latino people. I found comfort in his words in that time and I turn to them again today:

I have proposed a different understanding of melancholia that does not see it as a pathology or as a self-absorbed mood that inhibits activism. Rather, it is a mechanism that helps us (re)construct identity and take our dead with us to the various battles we must wage in their names— and in our names.

As a Latin@ people, we are not a trigger warning culture, but a reverent one. We carry the names of those we have lost as incantations and blessings to anoint communities that are hurting and seeking a space to heal.

In the tradition of naming the deceased to welcome them to continue dancing with us in our ceremonial centers, we say the names we have learned aloud to remember their legacies—to remember their pilgrimage:

Edward Sotomayor Jr., 34 years old

Stanley Almodovar III, 23 years old

Luis Omar Ocasio-Capo, 20 years old

Juan Ramon Guerrero, 22 years old

Eric Ivan Ortiz-Rivera, 36 years old

Peter O. Gonzalez-Cruz, 22 years old

Luis S. Vielma, 22 years old

Kimberly Morris, 37 years old

Eddie Jamoldroy Justice, 30 years old

Darryl Roman Burt II, 29 years old

Deonka Deidra Drayton, 32 years old

Alejandro Barrios Martinez, 21 years old

Anthony Luis Laureanodisla, 25 years old

Jean Carlos Mendez Perez, 35 years old

Franky Jimmy Dejesus Velazquez, 50 years old

Amanda Alvear, 25 years old

Martin Benitez Torres, 33 years old

Luis Daniel Wilson-Leon, 37 years old

Mercedez Marisol Flores, 26 years old

Xavier Emmanuel Serrano Rosado, 35 years old

Gilberto Ramon Silva Menendez, 25 years old

Simon Adrian Carrillo Fernandez, 31 years old

Oscar A Aracena-Montero, 26 years old

Enrique L. Rios, Jr., 25 years old

Miguel Angel Honorato, 30 years old

Javier Jorge-Reyes, 40 years old

Joel Rayon Paniagua, 32 years old

Jason Benjamin Josaphat, 19 years old

Cory James Connell, 21 years old

Juan P. Rivera Velazquez, 37 years old

Luis Daniel Conde, 39 years old

Shane Evan Tomlinson, 33 years old

Juan Chevez-Martinez, 25 years old

Presente.

And to those who have not been named yet, but we feel their spirits in our hearts.