The notion of a revived “religious left” has gotten a flurry of press recently, including here on RD. In a recent piece, Daniel Schultz makes the case any model of “revival” that depends on changing the “soul of the nation” with moral argument is bound to fail.

Schultz argues that American tribalism is so thoroughgoing that we have no shared or universal values to which we can appeal. As he writes,

Our nation doesn’t have a soul. It has a moral narrative if anything, and that a contested one. Even to the extent that America can be said to have a soul, that thing is a dark, twisted and brutal thing. Hasn’t anyone ever read Moby Dick? The Fire Next Time? People don’t want to redeem the “soul” of the nation. They don’t even want to do the right thing, half the time. What they want is for their ethics to be normative. Let’s be honest about that.

Schultz suggests that religious progressives might look to the strategies of the Indivisible movement, started by former Democratic staffers: building power through grassroots politics, in small cells that focus on cultivating leadership and organizing skills—rather than lionizing one or two moral paragons through symbolic actions (the usual domain of the religious left).

In other words, a carefully crafted moral message won’t convince people, but building power will.

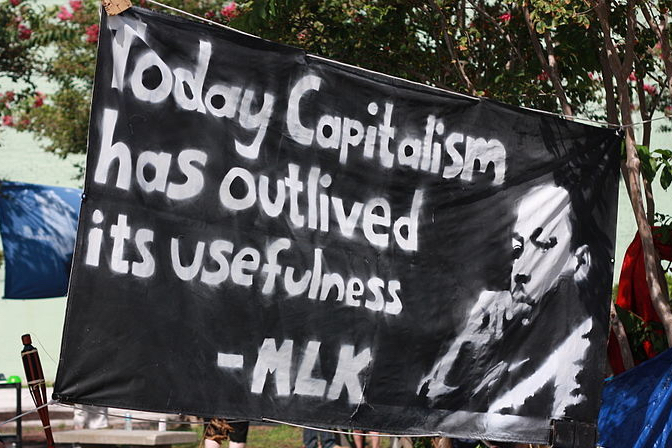

Happily, Schultz suggests that some of this is already going on. Rev. Dr. William J. Barber, II, founder of Repairers of the Breach and architect of the Moral Mondays movement, does appeal to a shared moral language, but he and his organization are building real political power—especially through Barber’s recent move to join the leadership of the new Poor People’s Campaign, the attempt to take up the unfinished business of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the last years of his life.

Regarding ethical frameworks, at the end of Schultz’s piece, he writes,

I say ‘Christian,’ because I of course am a white Protestant Christian, and because people like me tend to dominate the conversation. But we might just as easily talk about Jewish moral commitments, or Muslim, or Buddhist, or secular. But which one should be normative? Why?

Schultz is right that politics is about building power to render normative a particular ethical framework over others. Unfortunately, his model for this politics—the Indivisible movement—is business as usual, another iteration of the progressive wing of the Democratic Party.

Instead, what we need to be doing is what the Poor People’s Campaign is doing — building political power through the unity of the poor to center the ethical framework of the poor and dispossessed. As Dr. King said, the poor are the only group capable of becoming a “new and unsettling force” who can “organize a revolution against the injustice, not against the lives of the persons who are their fellow citizens, but against the structures through which the society is refusing to take means which have been called for, and which are at hand, to lift the load of poverty.”

If the poor are to become a “new and unsettling force” with real political might, we must first achieve the unity of the poor.

The political establishment has a vested interest in keeping the poor divided — a strategy that W. E. B. Du Bois called, in his seminal 1935 text Black Reconstruction, “plantation politics.” During the Reconstruction period, Du Bois explains, plantation owners fought against the possibility of a new economic democracy by extending the slave system, pitting poor whites against black freedmen to divide the Southern working class in order to avoid the development of a unified, robust labor movement in the South after the Civil War.

Today, the powers that be continue to utilize a divide-and-conquer strategy to keep the poor divided along color lines and other lines of division.

The original Poor People’s Campaign was King’s solution for building the unity of the poor as a class as a prerequisite for building political power. Indeed, one of the most striking images from the first Poor People’s Campaign is a political cartoon that depicts several pairs of feet walking in unison, labeled as belonging to poor folks of many races — poor whites, blacks, Puerto Ricans, American Indians — and a pair of worried politicians speaking together in the background, with a caption that reads, “What worries me, senator, is that they’re getting into step.”

The original Poor People’s Campaign was King’s solution for building the unity of the poor as a class as a prerequisite for building political power. Indeed, one of the most striking images from the first Poor People’s Campaign is a political cartoon that depicts several pairs of feet walking in unison, labeled as belonging to poor folks of many races — poor whites, blacks, Puerto Ricans, American Indians — and a pair of worried politicians speaking together in the background, with a caption that reads, “What worries me, senator, is that they’re getting into step.”

Building the unity of the poor and dispossessed is itself an act of building political power. Yet talking about centering the ethical framework of the poor isn’t the same as romanticizing the poor; it doesn’t mean that the average poor person is more moral than any other person. Talking about the leadership of the poor doesn’t mean tokenizing poor people by putting them at the front of your rally or press conference.

Centering the ethical framework of the poor as a class means learning from the innovative ways the poor have frequently been forced to come up with to survive and thrive in a society that has given them very little.

Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis, co-director of the Kairos Center and co-chair of the new Poor People’s Campaign, often tells the story of Philadelphia’s Tent City in the mid-1990s. Rev. Theoharis puts it this way in the introduction to her recent book, Always with Us? What Jesus Really Said about the Poor:

Tent City became a community and church much like the first Christian communities. There, homeless families of various races lived together, sharing donated toys, clothing, food, and toiletries. One disabled veteran was dropped off at the lot by an ambulance from the VA hospital because he had nowhere else to call home. A sixteen-month-old boy took his first steps among the rocks, rubble, and garbage left when the Quaker Lace Factory burned. Just as in Deut. 15:4 and Acts 4:34, there was no needy person there. When families were evicted and moved to Tent City, they would present their food stamps to the community. When someone needed to go to an appointment, families would volunteer to do childcare and pool their money to pay for bus fare. When it was hot, people in the surrounding neighborhood would drop off water, juice, and sometimes popsicles for the kids …

A miracle took place at Tent City — a miracle, that is, if we believe that feeding everyone is impossible without a miracle. Perhaps it was the sharing of what the families brought with them; perhaps it was the donations from those who had more than enough — including local religious congregations — in the surrounding city and suburbs; and perhaps it was God’s work of creating something out of nothing. While the families who moved there had very little, somehow food and other necessities were abundant at Tent City…

Tent City was a project of the Kensington Welfare Rights Union, an organization in the lineage of the original Poor People’s Campaign that is also an important part of the history of the Kairos Center and its predecessor, the Poverty Initiative. Organizations like the Kairos Center have been building toward the new Poor People’s Campaign for many years, primarily through raising up grassroots leaders from the ranks of the poor and dispossessed, and connecting organizations and leaders across color lines and other lines of division in their many struggles to end poverty and ensure basic human rights throughout the country.

The Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival is the fruit of these efforts, and its first era will culminate next year in forty days of action and civil disobedience in Washington D.C. and state capitals across the country, marking the anniversary of Dr. King’s Poor People’s Campaign with renewed resistance in the fight to end poverty, led by the poor.

The Kairos Center has gotten some press recently through the usual religious left framework — such as the recent healthcare protests in D.C. and a press conference at NY City Hall and meeting with the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. However, there is a fundamental difference between the position of Kairos and the usual idea of the religious left. It isn’t just that a properly crafted moral message will reach the hearts of generally good-natured American believers and turn them into supporters of something like the Poor People’s Campaign.

Instead, it needs to be clear that there is no potential for a moral revival in this nation without centering the leadership and unity of the poor and dispossessed. It is the ethics of the poor that need to be made normative if we are ever going to see the “radical revolution of values” that Dr. King called for in his famous “Beyond Vietnam” speech at Riverside Church in 1967.

It is the poor and dispossessed as a class whose ethics and struggle must be centered if we are going to have a real moral revival — not the ethics of the “religious left” or of progressive Democrats. Luckily, doing just that — centering the leadership and unity of the poor in all our attempts to create change in this country — is not at all contrary to the values of those of us who identify as Christian.

Indeed, as a poor person himself, Jesus was in fact the leader of a social movement of the poor and dispossessed, not the purveyor of some abstract, universal morality—that would have been the Roman Empire.