Organized prayer at state legislatures may be legal, according to the Supreme Court, but this week has shown that it’s also divisive, unnecessary, and wrong.

In Pennsylvania, a Christian state rep sought to intimidate a newly elected Muslim colleague with a bitter, vitriolic prayer that has caused untold discord and division in an already politically divided House.

Meanwhile, in the Georgia House of Representatives, Rep. Trey Kelley invited his father, Doyle Kelley, to deliver a 12-minute harangue on hellfire and damnation.

Kelley spent his first 10 minutes on a sermon that detailed how people who do not adhere to his particular brand of religion will be eternally tortured in hell, “Seven million people [in Georgia] … are lost are dying and on their way to Hell.” He read from Philippians 4 and Colossians 3 and even asked for a few “amens.” He also preached to this body representing all Georgians that “a person can only experience true peace as they come to know Jesus Christ as their Lord and Savior. If you don’t have peace in this room today it may be because you don’t know Jesus Christ as your Lord and Savior.”

After the sermon he prayed, sticking to the damnation theme:

I thank you once again for your son, Jesus Christ, for the one who died on the cross for my sins and for the sins of the people in this room, because of our belief in him we can have everlasting life. God, I’ve heard the saying, ‘Eternity is too long to be wrong.’ So God, let us be right about where we are going to spend eternity.

Kelley preached hellfire, not just for non-Christians generally, but specifically for all non-Baptists. The sermon embodied the worst religious tendency: I’m right, you’re wrong, and you’re going to hell. It was division writ large.

When the Supreme Court first upheld legislative prayers in 1983, the six-judge majority did not apply any constitutional test, but simply concluded—based on some lopsided history—that the framers thought prayers were just fine. Legal principle was sacrificed to cherry-picked history. Justice Thurgood Marshall attacked this error in his dissent: “if any group of law students were asked to apply the principles of Lemon [the case that determines whether the separation of state and church has been violated] to the question of legislative prayer, they would nearly unanimously find the practice to be unconstitutional.” As he so often was, Marshall was right.

The past couple of weeks have shown the country that, even though the Supreme Court has said prayers are constitutional, government bodies should stop organizing them. They are divisive, intimidating, coercive—and certainly unbecoming in bodies that represent our increasingly pluralistic communities.

If these prayers were to end tomorrow, what would happen? Legislators who want to pray would still be able to pray at their desks, in their office, or at any time.

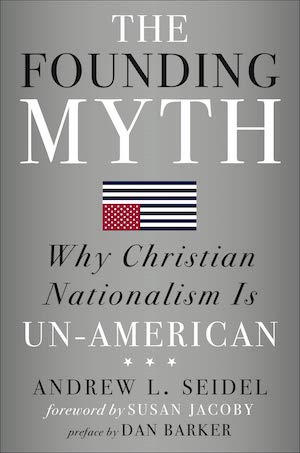

The problem is that legislators don’t want to pray, they want to be seen praying. They want to appear pious for political reasons. This treats religion as a tool of political manipulation and is, in James Madison’s words, “an unhallowed perversion of the means of salvation.” These prayers degrade both religion and our politics. And they open the halls of power to the worst strains of Christian nationalism.

Finally, it should not be atheists like myself making this argument, but true Christians who would rather not see their religion “perverted” for political ends. In his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus condemned public prayers as hypocrisy: “when you pray, do not be like the hypocrites, for they love to pray standing in the synagogues and on the street corners to be seen by others.”

Without organized prayer, nothing is lost. Legislators can still pray on their own. And if some legislators still feel the need to get together for a moment of solemn reflection before they roll up their sleeves and get down to business, they should take a page out of Thomas Jefferson’s book and, instead of prayers, “contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should ‘make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof’ thus building a wall of separation between church and state.”