Christian fundamentalism was invented in an advertising campaign, according to a new book by historian Timothy Gloege. The all-American brand of “old-time religion” was developed by an early captain of consumer capitalism—who wanted to sell pure Christianity like he sold breakfast.

Guaranteed Pure: The Moody Bible Institute, Business, and the Making of Modern Evangelicalism

Timothy Gloege

University of North Carolina, April 27, 2015

If you asked people for a short list of the most important religious figures in the early 20th century, Henry Parsons Crowell probably wouldn’t be on it. Who was Crowell and why was he important?

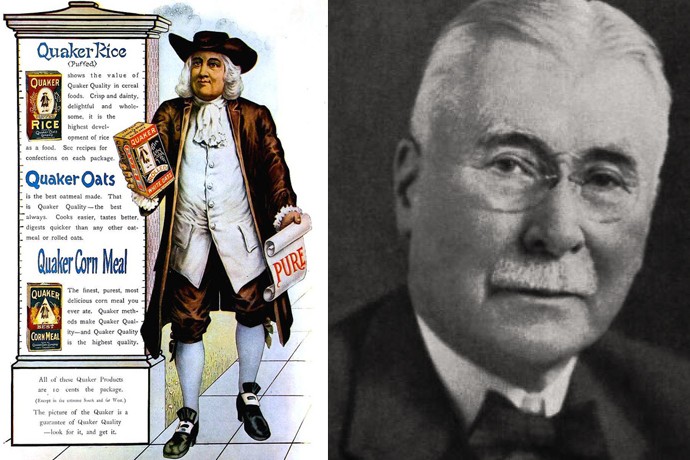

Henry Parsons Crowell was a purveyor of oatmeal. He is best known by business historians as the president and founder of Quaker Oats, one of the pioneers of the branding revolution. He used a combination of packaging, trademark and massive promotional campaigns and transformed oatmeal from a commodity into a trademarked product.

Crowell took oatmeal that used to be sold out of large barrels in your general store, put it into a sealed package, slapped a picture of a Quaker on it and guaranteed it pure. Now it no longer mattered who you bought your oatmeal from, only what brand you chose.

A company’s reputation was once rooted in its owner, but the trademark created this virtual relationship with consumers that was pure fiction. The trust that is engendered by a Quaker has no relationship to the company itself. There are no Quakers involved in that. Crowell was a Presbyterian. He bought the trademark, a very small mill had the trademark and he said, “oh, this engenders trust, so I’m going to use this to sell my oatmeal.”

This was quite controversial at the time, though today that’s just how things are done. Quakers sell oatmeal and friendly animated lizards sell us car insurance.

One of the key arguments in the book is that he is using similar strategies in religion as well. As president of Moody Bible Institute, Crowell pioneered the techniques of creating trust in a pure religious product, packaging and trademarking, as it were, old-time religion.

How is the story of American capitalism also the story of modern American Christianity?

They’re cultural twins. They’re both drawing from the same set of ideas about the nature of self and society that was, frankly, new in the days after the Civil War. These are the idea of the individual being the basic unit of analysis, that individual choices are really what matters, that’s how you create yourself.

Whereas older ideas would see society as more of an organic unity, they see it as a collection of individuals.

One of the main points of my story is that the particular arrangement we see today of evangelicals’ alignment with business is not a new phenomenon. It can be traced back, specifically to the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. It was not there before. And it did not start after World War II. It really started here.

I’m also arguing against the idea that American Protestantism has always been guided by the logic of the market. That’s not true. There was a shift in American Protestantism which is connected to this other shift in economic history.

What shifts in the business world is there’s an underlying assumption that I make my economic decisions out of my own self interest, that everybody is doing that, and society is better off as a result, rather than have to make business decisions in light of how it might affect society—that’s not the question. It’s all about me and my rational choices and other people’s rational choices, which makes it into a game of sorts. And this isn’t always the way that it was.

In the same way, religious experience is re-conceptualized as individualistic.

In the traditional, “churchly” model—if I can make a generalization here—when you had individual Bible reading, the person who is superintending your interpretation of the Bible and saying whether you’re believing the right thing or the wrong thing is your minister. And your minister knows what’s correct based on going to seminary. That belief is then superintended by a theological tradition that precedes that credentialing. All these things bear on what the proper interpretation of the Bible is.

But in the evangelical context, it is all about you and God.

This is the fiction evangelicalism is predicated on: there is this plain reading of the Bible and anyone who sincerely sits down and reads the Bible, regardless of their education, regardless of their background, can get it. But you end up getting problems. People end up interpreting the Bible in ways that disrupt society. They start thinking that miracles are a common occurrence, so they decide they don’t need to take medicine, don’t need to give children medicine. And children end up dying. They read the Bible and see that men are married to more than one women, so they are challenging established family norms.

And you have people who are reading the Sermon on the Mount, and Jesus’s talk on money, and they say modern capitalism is evil and abhorrent to God.

There is an ideal of what will happen when evangelicals read the Bible, but it doesn’t always work out. There’s a dynamism that comes with plain reading, but in tension with that is the threat of disorder. So it’s vitality versus disorder.

What happened historically in American Protestantism is that you would go in an evangelical direction, you’d have revivals, you’d revitalize the faith. Then things would start to go a little nutty and at least respectable middle class Protestants would swing back in a churchly direction. They would turn back to tradition. They would turn back to church and say these things are important and reimpose order with church.

What Crowell did, and what makes Crowell important to my mind, is that he created a way to continue the evangelical movement without having to resort to a churchly mode of imposing order.

How did he do that?

The first step was to create a new standard of orthodoxy. Traditionally, you had a Presbyterian orthodoxy, a Methodist orthodoxy, an Episcopal orthodoxy, and so on. There is no such thing as just “conservative Protestantism.”

So that was the first job that Crowell had to do, was to create this fictional orthodoxy, this conservative Protestantism, this set of fundamentals that anyone, any conservative of any denomination [could] ascribe to and could use to differentiate themselves from liberals.

The way that he does this is through the publication called The Fundamentals. It is the publication that gives the fundamentalist movement its name—a 12-volume set of theological treatises written by various scholars that claim to put forward these fundamentals of the faith.

Most people do not read The Fundamentals. When you do, what you find is that there are huge gaps in what would be a traditional creed. There are any number of points of theology that, actually, most of Christians would see as essential—ideas about who God is, what is the nature of salvation, all of these things—are not brought up. Because they would be too controversial among conservatives. And, when you look at the subjects that are brought up, articles regularly contradict each other. There is no unified creed in any sense.

What The Fundamentals is doing, if not laying out a precise creed, is creating the impression of an orthodoxy.

It was successful mostly in bringing together conservatives in all these different denominations who were feeling embattled by liberalism, who were feeling like a minority, and who felt like they were alone. The Fundamentals ended up reaching over 300,000 subscribers, at the height. The publication, as a publication, creates this nation-wide imagined community that cuts across denominational lines.

It is more imagined than real, though. If you were to ask these people what constitutes this inter-denominational orthodoxy, they would come up with very different lists. But for Crowell, his background is in consumer products—”fundamentalism” is a label and functions like a brand.

Crowell does this at the helm of Moody Bible Institute. If we back the story up, how does Dwight L. Moody, the famous evangelist, fit into the history of American capitalism?

The importance of Moody is in making the initial links between economic identities and religious identities. Prior to Moody, those things were much more distinct. These were not models that were really used.

It’s important to remember that Moody was born and raised completely outside of orthodox Protestantism. He was raised a Unitarian. He had a grade school education. He had no theological training whatsoever. He started going to church because he had to as a requirement of his job. He didn’t enjoy it or get anything out of it.

Then a Sunday School teacher came to him at work and told him that Jesus loved him—that was it, he converted.

Moody started to understand his relationship with God using the things he knew best, which was his life in business—in sales, specifically. When Moody decided to become a full-time revivalist—without any sort of theological training, mind you—he was God’s salesman, inviting his listeners to enter into a personal relationship with God.

He started to conceptualize the authentic believer in terms of being a good Christian worker. What mattered wasn’t what you believed, it was, are you submitted to God? Moody gets his idea of the ideal worker from his industrialist friends in the Gilded Age who want their workers to be submissive, hard workers and pragmatic problem solvers: he conceptualizes the Christian worker in those terms. He infuses his ideas about faith with metaphors of work.

You write that the captains of industry, business leaders and town fathers would sit behind Moody on the stage as he preached. Why did they—literally—back his Gospel message?

Those elite men and women sitting behind Moody saw him as the solution to the problem of social disorder and labor unrest because he came from this same class. He was born into poverty, he regularly used bad grammar and mispronounced words, yet he lived in harmony with elite businessmen. He did not begrudge their success or question their ethics. He would say this was because he had this conversion experience and he had a personal relationship with Jesus.

A lot of these business leaders thought this might be the solution to social disorder: If only we could covert the working classes, they would be like Moody and stop being jealous of our success and we could all get along. Some of Moody’s business supporters were very sincere, but there were others who were a little bit less sincere and just saw it as a solution to the problem.

But of course when you have those sort of people sitting on the stage behind you, that’s not going to attract the working classes that you want to convert. Who it ended up attracting, especially as Moody became a celebrity, was the respectable middle classes.

What Moody’s message did for the middle class is to make people feel real and alive in a way the older, churchly Protestantism did not. Moody used analogies from their business experiences that made sense to them. He actually changed the definitions of key theological terms, putting them in business terminology. So, for example, he says, “I have faith in God in the same way I have faith in the stock market.” It made their faith feel real to them in a way it might not have before.

Also, what it does is to naturalize these very new economic ideas and practices.

How does Moody Bible Institute come to be led by a captain of industry, this oatmeal man who is an expert at branding?

Crowell started at Moody Bible in 1901 and was basically in charge starting in 1904, 1905—a time when the Institute was in crisis. The major problem was that Moody Bible Institute was not converting the masses and restoring social order. It was reaching a very small portion of working class people, and, at the turn of the 20th century, those working class people who were reached were not becoming respectable members of the middle class—instead they were getting involved in the Populist movement, which was using the Bible to critique capitalism and critique professionalization.

These working class people were also getting involved in the Pentecostal movement and transgressing racial boundaries. There is even an earlier incident where Ruben A. Torrey, the most prominent evangelist working with Moody, got involved in faith healing because of his “plain reading” of the Bible.

Torrey has a similar business-metaphor interpretation of the Bible to Moody, but he gives it his own particular spin. Torrey said very boldly that prayer is a God-ordained way of people getting things—the Bible becomes a catalog, a practical catalog of God’s promises.

The big problem, of course, is that answers to prayer don’t happen consistently. For Torrey, there was a tragic event where one of his daughters had diphtheria and he believed God was calling him to pray for her healing. This was in 1898 when there was a well-known anti-toxin for the treatment of diphtheria, but he refused to call a doctor and instead relied solely on prayer. He had a change of heart, but was too late and his child died. What do you do with that? This becomes the problem.

Throughout the 1890s amid growing populist discontent, groups of working class and lower middle class evangelical radicals were using beliefs and practices similar to Torrey’s to challenge the rising professional classes and in some cases the entire capitalist order.

So, this message of Moody’s and Torrey’s that was supposed to bring social order starts to bring disorder.

By 1901, everybody was bailing on Moody and they were losing their financing. They needed new business supports and eventually brought Crowell in, who had been influenced quite a bit by a teacher who was teaching at Moody Bible at the time.

What Crowell did—and what makes him so important to my mind—is that he solved the problem that had plagued individualistic, evangelical religion since it first emerged during the First Great Awakening in the eighteenth century. (When things started to go a little nutty, respectable middle class Protestants swung back to an emphasis on church and tradition.)

Crowell figured out a way to impose order on evangelicalism, but without having to resort to churchly guardrails. He used the techniques of consumer capitalism that he knew so well, packaging and trademark and massive promotional campaigns.

How has Crowell shaped the modern religious landscape?

The Moody Bible Institute pioneered a means of generating a reputation of being a purveyor of pure religion. Today these business techniques are everywhere. The biggest churches in America have no denominational affiliation, and they are filled with respectable, middle-class people. This would not have been the case in the early 19th century, where a denominational identity was a normal part of a middle class identity.

In Crowell’s business experience, purity is at the foundation of his business success. Quaker Oats became what it was because he was able to make people suspicious of the oatmeal you would shovel out of a barrel, and his sealed box with the picture of a Quaker on it was the pure alternative. In every single advertisement that he created in the first 30 years of the company’s existence, the Quaker was always holding a scroll and the single word “pure” was written across it. That was a central idea, for Crowell.

He looked at religion in the same way. There is pure religion and there is impure religion. His question was “how do you make the religion I know is pure appeal to the consuming public?”

The solution he found, to promote modern evangelicalism as “old-time religion,” has worked for a century.