Just a day after the massacre in the historic Emanuel AME Church of Charleston, the son of one of the victims, Sharonda Coleman Singleton, offered forgiveness to Dylann Roof. As more of the victims’ family members emerged to publicly forgive Roof I found myself caught between the Christian imperative to forgive that had driven them to do so, and an emotion that was irreconcilable: anger.

I am not enraged, nor do I seek vengeance, but there is a clear and concise anger born of my inconsolable grief both for the tragedy itself and for the children forced into a position where forgiveness for such a wretched act was assumed. I am angry that these children were catapulted into the company of other survivors of inane violence against blacks, such as Mamie Till-Mobley whose response, as Cornel West frequently writes, was: I don’t have a minute to hate, I’m gonna pursue justice for the rest of my life.

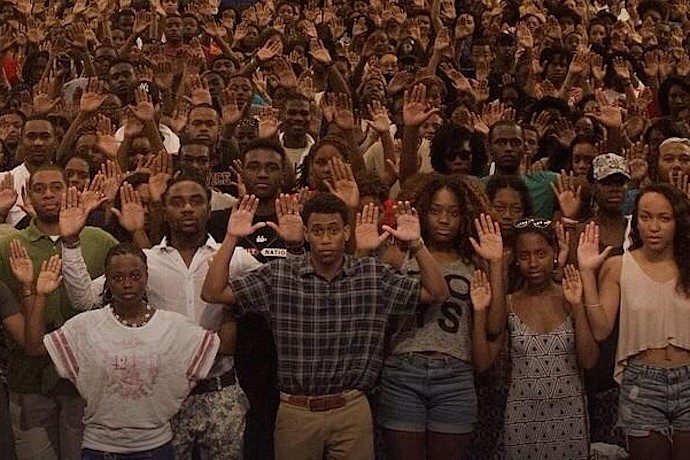

In our post-Ferguson moment, collective anger has been one of the emotions fueling the protests in Baltimore, New York and elsewhere. Emotions are running high. Rather than flashpoint events, each new tragedy is one of a continuous string doing its work on the human psyche. However, in the midst of all of the speeches and rhetoric, anger is seldom acknowledged. And if it does, it’s only in the context that it is undesirable and that one should move on from it to something else.

Part of that is fueled by respectability politics that govern much of public speech, but it’s also due to an innate cultural sensibility that anger is not a healthy emotion to have. The Christian tradition doesn’t uplift anger as a human experience worth having. Anger is reserved for God. The fact that the liturgical calendar doesn’t have a season for anger, or include in its canon a “Righteous Indignation” Sunday, speaks to just how ingrained our anti-anger theology truly is.

Forgiveness is something on which Christianity hangs its hat. Not only is it a biblical cornerstone of the faith, it’s also a cultural expectation that, if you’re a Christian, society requires it of you. The hurdle for forgiveness is pretty high and the road is paved with hurt and pain. While forgiveness may be the final resting place after an emotional roller coaster, Christians should not be taking a shortcut around anger to get there.

James Cone, the founder of black liberation theology, once said that his first book, Black Theology, Black Power, was written in the five weeks immediately following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. He famously said that he wrote the book because he was angry. Long considered “America’s angriest theologian” (a moniker he has donned for all these years), Cone’s anger not only speaks of the experience of a civil rights era sentiment, but for a millennial generation quickly discovering that the causes of Cone’s anger are also the genesis of their own.

Anger, as evidenced by Cone, the author of twelve books, has the power to be sustainable and even productive. Cone’s anger, like the anger that is the ubiquitous in this post-Ferguson era, is that of righteous indignation. While I have tremendous respect for the families of those killed by Dylann Roof, I fear that the move to immediately forgive can, in times like this can, serve to absolve Christians from addressing the issues that caused the situation. More specifically, my fear is that to skip over anger, to not allow one’s humanity to have a spiritual encounter with righteous indignation, is to avoid the desperately needed conversation about racism and white supremacy.

The fact that a new generation is encountering anger so frequently, aided by social media, speaks to an ever-growing need for the Christian experience to address it. With the recent Pew study about the dwindling numbers of Christians in the mainline denominations, there has never been a better time for churches and denominations to take some time and energy to craft a theology that more fully reckons with anger.

The notion of a “theology of anger” was spurred from conversations with a colleague and friend who’s connected to both the academy and the clergy and who is increasingly having pastoral care moments where anger is the predominant emotion. What we discovered is that there were no theological or ecclesiastical resources to deal with anger in terms of righteous indignation; to deal with a wrong that one felt the need to right.*

Part of our frustration wasn’t just fueled by the actual events themselves, but by the ways in which we felt part of generation that was in-between; caught in the middle of traditions that we love and a future we had yet to determine, yet still forced to exist in the present. This was apparent in the ways that the institutional black church—the mainline denominations as well as the broader evangelical church—have ignored anger in the face of injustice and tragedy. We were frustrated that tradition far too often seemed to win the battle of wills. These skirmishes with frustration were also allowing my colleague and myself to self-identify that we too, were also angry.

While social media can be a collapsing audience that emerges with a singularity of thought that may or may not be factually correct, the sentiments of anger were apparent in some strains during and following the livestream of Mother Emanuel AME on the Sunday morning following the shooting.

For many, not hearing the waves of righteous indignation justified a complete rejection of the entire worship experience. While this may not be the place or time to parse that specific dynamic, this is a clear example of a generational difference where there may now be an expectation and need for anger in their spiritual and religious spaces. For many millennial black activists, one’s blackness is not divorced from one’s spirituality. And ultimately, for many, spirituality comes second.

For many, it was not that the family of Dylann Roof’s victims actually forgave, it was how immediately they did so. The conversation expanded beyond the Charleston murders to the long history of forgiveness in the black American experience as a response to crimes against humanity.

Forgiveness, to the black activist of the 21st century, can sometimes be seen as a form of white appeasement; a way in which white fears are assuaged that blacks will not revolt against the horror that was committed. The Atlantic‘s Ta-Nehesi Coates tweeted that he “Can’t remember any campaign to ‘love’ and ‘forgive’ in the wake of ISIS beheadings,” which illuminates the strong emotions against forgiveness in the context of this particular tragedy in Charleston. The Christian obligation to forgive appears counter-intuitive to those within a Black Lives Matter moment who are angry and filled with righteous indignation, trying to discern the next move of rebellion or revolution.

This is not a campaign to do away with forgiveness, but rather an effort to make the case that the black Christian experience needs to include anger. In light of our country’s ongoing inability to deal with race, and the tragedies that occur as a result, this encounter with righteous indignation is especially necessary to black churchgoers. A space must exist in the pulpits, with sermons that acknowledge anger and righteous indignation, as well as in the curricula of Christian education departments. And yes, even in the sacred spaces of a mid-week bible study.

Correction: This post initially claimed that “Moses was prevented from seeing the Promised Land because he killed an Egyptian slave master for harshly treating a Hebrew slave.” In fact, Moses was not permitted to enter due to another, different display of anger: striking the rock to produce water for the truculent Israelites. The author concedes that he may indeed have been taken over by “a bit of black church midrash” while writing it. — ed