Within the first dozen words of Chris Hedges’ recent article on liberal Protestants we learn both that its institutions are “demonic” (bad!) and that it is committing “suicide” (also bad, or at least lamentable).

It is not clear whether both things can be true at once—can it be so demonic if it is dead, and can its death be unfortunate if it is demonic? Nor do Hedges’ arguments—which start from a controversy about funding Union Theological Seminary in New York (UTS), then range widely to condemn liberal church leaders and valorize left-of-center activists—advance his agenda. Rather he offers an instructive example of an all-too-common genre: radicals who, in effect, echo right-wing talking points about the dysfunctions of the Protestant left: fomenting conflicts, exaggerating weaknesses, and presenting dilemmas in the least flattering light.

I wanted to like this article because Hedges’ good guys are about the same as mine—peace and justice activists and intellectuals with a foot in religious traditions. Appealing to Reinhold Niebuhr for authority, he presents them being driven to the margins of his demonic, and now suicidal, institutions. We agree that liberal churches include people who sell out overtly to neoliberal imperialism—Hedges calls this “Christian heresy”—or sell out covertly with rhetoric of tolerance and “tepid church piety.” Both of us would like to see more good guys; both are exasperated when existing institutions do not provide room for them to maneuver.

Unfortunately, he moves the cause backward.

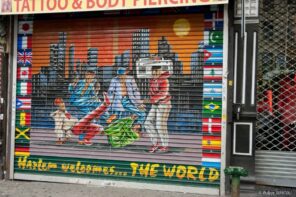

Much of his article examines a decision by UTS, one of the Protestant left’s flagship institutions, to raise money by selling “airspace” above the northeastern part of its quadrangle for luxury condominiums, with the proceeds to be used largely for deferred maintenance and renovations of the rest of its property. Hedges quotes a student activist who sees this as a “middle finger” to nearby Harlem—although one wonders why the steeple of next door’s Riverside Church, other high-rises in the neighborhood, or even the surrounding Columbia University as a whole have not already nailed down this role.

The key reason UTS needs money is because of the stands, mainly commendable in Hedges’ terms, that it has taken over the years. Many of its high-rolling trustees and donors abandoned it over its social justice stands in the 1960s, and neoconservatives have been trying to shovel dirt on its grave ever since. There is nothing new about this. UTS has sold off parts of its property several times in the past to stay afloat, and Columbia University has already taken over parts of its quadrangle.

Will the current sale be enough to stop the bleeding? Maybe. This depends largely on the wider trajectories of liberal churches, as well as fine print to which Hedges and I are not privy. Is it a fatal compromise? I seriously doubt it. Is the UTS leadership perfect? Surely not, but let’s get real: perfect compared to what? Anybody appealing to Niebuhr should be smart enough to ask that question.

Hedges frames his complaint with boilerplate about numerical declines in mainstream churches. We could slow down to debate whether this is insightful, since for 150 years mainline churches have been a minority that could not credibly speak for Catholics, evangelicals, or racial minorities; and activists have long been a minority within that minority.

It is far less clear than pundits assume that its limitations are more severe today than before its struggles after 1970—although its collapsing cultural prestige is a real problem.

But rather than slow down, let’s grant a steep decline for the sake of argument. Decline to what level? Hedges notes that Catholics, who still have a 21% demographic slice, are “being decimated,” yet this is seven times more people than watched the Democratic Presidential debates. That number, combined with 36 million liberal Protestants (with “growing irrelevancy”), is just a bit below the viewership for the Super Bowl.

As to causes of decline, if we move to the margins of demonic institutions does this slow it down or speed it up? He calls for greater vitality on the left, and I agree that this is better than steering right or being tepid—but at best what has happened on this front has been a wash for liberal Protestants in institutional terms. As I’ve argued before, amid decline from birthrates, leftward moves (not least by institutions like UTS) have probably repelled roughly an equal number of people as they have attracted—and meanwhile there has been a net loss of wealthy donors and elite allies. One might expect Hedges to approach this as a trade-off. Indeed it is a sort of tradeoff for him—“a heads you win, tails we lose” variant between selling out and abandoning ship.

It is unclear how invested Hedges is in the survival of liberal institutions—but either way, it’s hard to see how his intervention is constructive. He poses a lose/lose choice: be a neoliberal tool or a lonely radical taking potshots at institutions attempting to figure out ways to thrive.

Granted, a win/win approach that maximizes the benefit of doubt in Hedges’ excluded middle ground is not more illuminating in every case. In fact, a signature problem of Protestant liberals is their tendency to hold out hope that rings false. Yet shouldn’t a flagship institution of liberation theologies get any benefit of doubt?

There is also a problem—more attuned to geeks but nevertheless galling—that the historical importance of Niebuhr was to argue against the sort of reasoning Hedges advances (mocked by Niebuhr as “purist” or “perfectionist”). This matter is complicated because Hedges is rightly accenting how pragmatic choices by institutional leaders are often dubious—yet a classic case in point is Niebuhr himself, who made pragmatic compromises that were largely commendable in the 1930s but far less so in the 1950s.

Still, the key point is straightforward if you want to think with the radical Niebuhr: keep your eyes on the prize, but be humble and realistic enough to embrace lesser evils.

Hedges and I agree that liberal churches are internally contested and that our “good guys” do not always win. We seem to disagree over whether significant institutional space is still available and what kinds of compromises are worth making to keep it. We also seem to have a different sense of whether religious contestation is somehow less important than contestation over Democratic politicians or TV programs—or than defending space in academia or journalism.

Are the choices available to the Protestant left as stark as Hedges presents them: either sell-out to “demonic” capitalist expediency or abandon the ship, and then, while bobbing in a lifeboat with other moral exemplars, jeer as it goes down? If this bleak vision accurately describes our options in some cases, so be it. It may be a place to unleash Niebuhrian realism. But does this accurately describe most cases? Why not push back against the conservative talking point that the Protestant left is dying and deserves to die sooner?

If there are both win/win and lose/lose cases to choose from, which choice is more suicidal?