Raised in an evangelical family in Texas, Macy Halford has been reading My Utmost for His Highest since she was fifteen. A daily devotional originally published in England in 1927, the book is so influential that even today the faithful can follow its immortal author, Oswald Chambers, via @myutmost on twitter.

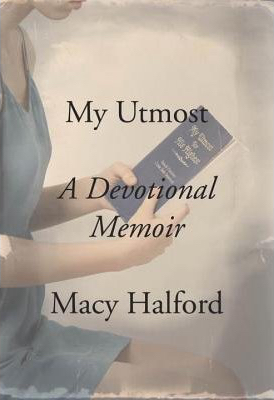

In a new memoir Halford considers the impact Chambers’ book has had on her personally, as well as its remarkable history. The debut author also describes her experience inhabiting the seemingly disparate worlds of The New Yorker magazine, where she worked for several years, and her Southern Baptist background and belief.

______

My Utmost: A Devotional Memoir

Macy Halford

Knopf, February 2017

Liesl Schwabe: In the book, as you’re recalling some of your early days at The New Yorker, you write, “It was not often that my childhood religion made an appearance in my New York life….” Can you say more about that time?

Macy Halford: I was raised to evangelize—to witness about Jesus and to spread the good news—and to do it in a Texas-big style. I rapidly realized that that style didn’t have any currency in New York (in addition to being an awkward fit for my personality); over time I developed another, quieter style of sharing my religion. In New York, I was never told outright not to be religious, but I did immediately understand that if I wanted to bring up my beliefs, I’d better be ready to have a serious discussion. It took me time to get used to this—then I came to appreciate it. It is a privilege to be able to discuss reality with people of differing viewpoints

Did you struggle at all with imagining an audience for this book? Were any colleagues ever dismissive of you or of this project precisely because it is such an honest exploration of faith?

I did ask myself who would want to read this book. And my answer was that I would. I loved that my family had raised me with faith and with religion, but I also didn’t fit perfectly into my church or the molds of religion [in Texas], and I thought of myself as a seeker. That understanding directed my voice. I also think, in some ways, all readers are seekers.

But I never experienced silencing by the secular or mainstream press, or at my liberal college. This is probably because I am liberal in my viewpoints and literary and intellectual in my writing style. So my religious belief is sort of subsumed in a language that this segment of society recognizes as its own. Where I’ve experienced censorship is from the other side—super-conservative branches of the religion who don’t think I “sound” Christian.

It’s one reason I’m liberal. I read Christianity as radical love and humility

I found your book refreshing because even as have chosen a different path, you’re still inclusive—of the faith itself, the culture, and your family.

A lot of that credit has to be given to my family. We all have to make an effort to include each other and the various beliefs that exist in our family. My book is really about a journey in faith—not a journey into faith or away from it. There’s no big moment.

Right. Daily life is pretty quiet.

Exactly. It’s not a big dramatic story.

How has the election been for you? It seemed like early on in Trump’s campaign, a lot of evangelicals tried to distance themselves from him, but there was a big shift once he became the Republican candidate.

Something like 81% of white evangelicals did vote for Trump, but I want to also emphasize that “white evangelicals” are not synonymous with a political party or agenda. The fact that they tend to vote Republican has to do with our political system funneling us into two broad categories, but within those categories, there’s diversity of opinion that goes unrepresented. I think that it’s very convenient for evangelicals to be treated as a voting bloc by politicians, preachers, and the media, because the closer the religion can be tied to a political party, the better for people seeking power on the basis of religion.

It’s important to me to say these two things are not synonymous. Republicanism is not Christianity.

There’s a reifying effect, too: If you are a white evangelical who did not vote for Trump, you are no longer considered a “white evangelical.” I do take care to call myself “evangelical.” Just because my political identity has shifted as I’ve gotten older doesn’t mean I cease to be evangelical. I still like the style of preaching and the fundamental principles of the “heart religion.”

I recently saw a picture of a sign from the 1992 March for Women’s Lives that said, “Religion is a bad joke and pro-life is the punch line.” Do you think that women have a particularly hard time balancing the ideals of religious life with day-to-day reality?

There’s a chapter in my book when I describe going to women’s Bible study with my mother, every Tuesday, while I was back in Texas for several months. At that Bible study, they were always very practically minded in helping women solve their problems. We don’t necessarily hear that when the men are preaching and running things, but it’s what women want and need.

I hate to generalize because each woman has her own experience. But is there a special struggle, different from men’s? Yes.

In that section of the book, at the women’s Bible study, you write that you wanted to continue your “experiment in perspective.” As you say, “I wanted to see both the whole picture and the detail.” That feels so relevant to right now.

I’ve been thinking about that a lot. It’s very difficult. I’m human. I’m not immune to anger or distrust. But Oswald wrote so much about this. During the First World War, when he was ministering British troops in Egypt, he saw German prisoners of war who were so sure that God was on their side. Obviously, the Brits thought so too. Oswald knew there were these divergent beliefs and he said that when you consider others, you should ask if you are looking with a “hard gaze,” meaning with superiority and judgment. He was always trying to cultivate a “soft gaze.”

I would never say that we shouldn’t be standing up for our beliefs or standing up for our rights or protesting. I think we should. But I also think that we can keep a “soft gaze” when looking at others.

In one passage, you write that rather than asking why you’re religious someone might ask why you’re religious in the particular way that you are. I love how that redirects the conversation and keeps ‘religious’ from being a yes or no question.

That’s definitely an idea I got from Oswald. He had this view of the universe as something quite wild, diverse, and unpredictable. He thought each individual was a unique creation. The basis of his idea of Christianity is this personal relationship with God. So, early on, I started thinking about how I was religious. It wasn’t exactly the same way I saw, or thought I saw, that people in my church were religious. Thanks to Oswald, I thought of myself as an individual.