Bill Schutt’s new book, Cannibalism: A Perfectly Natural History, is a startling reminder of how strange it is to be flesh. Over the course of 300 pages, Schutt covers everything from cannibalistic spider sex to the siege of Leningrad. The book is an encyclopedia of carnivory.

It’s worth reading. Cannibalism threads through the fictions, scriptures, and rituals of cultures around the world, including 21st century America. It’s one of our great taboos. And while Schutt can be an entertaining writer, he’s not sensationalist. Instead, he demonstrates how cannibalism can get at the unstable lines we draw between custom and taboo, human and non-human, and self and other.

A spirit of uncertainty is there from the start: what is cannibalism, anyway? A firm definition is surprisingly difficult to pin down. Dining on the meat of another human being is a clear-cut case. But is eating a chimpanzee or a bonobo definitely not a kind of cannibalism? What about taking pills made from powdered mummies? That was a remedy in European pharmacies into the 20th century.

Is eating your own placenta an act of cannibalism? What about eating someone else’s placenta?

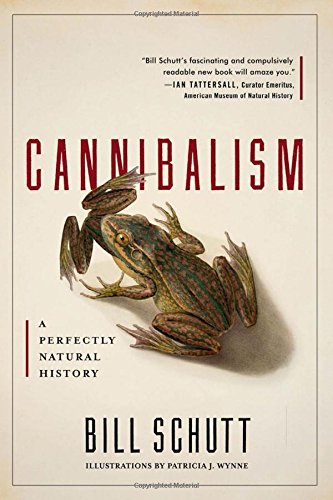

Cannibalism: A Perfectly Natural History

Bill Schutt

Algonquin Books, February 2017

Stop thinking in culinary terms, and the question gets even thornier, because bits of human bodies cross over into other human bodies all the time. Ailing patients accept donated organs and transfusions of blood and plasma—the latter harvested from the poor, who receive a few dollars an hour as machines draw their blood, centrifuge out the precious fluid, and then inject the denuded ichor back into their veins.

Infants suck milk from their mothers. Lovers swap spit (and more).

Many Christians believe the Eucharist to be the literal flesh and blood of Jesus. Is taking the host an act of cannibalism, too?

Schutt is a biologist who studies bats, and he’s at his strongest playing tour guide to the many ways that animals consume members of their own species. Polar bear males sometimes eat cubs. Tadpoles chomp on each other in the pond. Certain species of spider consume their partners’ bodies in the midst of mating. Some fish will eat their own eggs and young. Filter-feeding marine animals like clams cannot control what comes into their siphons, and they suck up their own eggs, sperm, and larvae along with other tasty sea creatures.

Some baby caecilians—a kind of legless reptile—chew on their mother’s body. This practice seems less strange when you realize that it serves the same function as breastfeeding. Only instead of milk, the caecilians are eating nutritious, quickly replenished layers of maternal skin.

What does any of this have to do with people? At its best, natural history writing reminds us of the staggering diversity of life, and it reminds us that nature and culture are not quite separate. At its worst, the genre treats some human beings like animals. Schutt does an admirable job of hewing to the first approach. Certainly, he’s interested in the animality of human experience. But, critically, he’s sensitive to all the ways that the term cannibal has been used to dehumanize people, too.

There’s a long history here. By labeling natives savages, colonial conquerors found pretext to savage the natives. In 1503, for example, Queen Isabella of Spain forbade Columbus and his crew from enslaving people in the New World, unless those people were cannibals. If they were cannibals, the Queen announced, Columbus could take them, put them in chains, and sell them wherever he pleased, inside or outside Isabella’s many realms.

Reports of cannibalism in the New World spiked.

In general, cannibalism is widely reported but difficult to confirm. Subjects will often tell ethnographers about it, but ethnographers virtually never see it themselves (the anthropologist William Arens famously argued that ritual cannibalism doesn’t really happen at all; many anthropologists disagree, or even accuse Arens of denying the self-reported experiences of indigenous peoples).

Meanwhile, starvation-driven cannibalism takes place in areas that are isolated by circumstance or siege, and it’s rarely discussed after the fact.

Still, human cannibalism happens, although perhaps more often in the imagination than in real life. Certainly, it’s ubiquitous in fiction, from the Grimm Brothers’ fairytales to the Hannibal Lecter franchise, which now includes books, movies, and a TV show, all of which profit from the frisson of watching cannibalism.

The eating of flesh is also central to Christian symbolism. Writing about the Eucharist, Schutt offers some fascinating historical details: Jews in Europe used to be arrested on suspicion of stealing and torturing the host. There’s also a mold that can make bread look like it’s bleeding, which Schutt, in full skeptic mode, suggests may be behind reports that the host itself has come to shed blood.

Schutt doesn’t quite seem equipped to go deeper. He skates through the familiar but is it literally flesh or not? question, without spending much time probing the experiences of believers, or teasing out the many shades of literalism. It’s a delicate topic in a sometimes too-glib book, and Schutt would have done well to spend more time with it.

When it comes to religion, Schutt also seems casual with the facts. He refers to the dietary guidelines in Leviticus as “Judeo-Christian law” (they’re part of Jewish law, but not Christian or Judeo-Christian law). Elsewhere, discussing the debate over transubstantiation, he refers to the “Roman Catholic leaders” who “thumb[ed] their collective noses at the upstart Protestants” during the Eastern Orthodox Synod of Jerusalem in 1672. He also quotes at length from a confession written at that synod.

But it was Eastern Orthodox leaders who gathered at the Eastern Orthodox Synod, not Catholics.

Still, I found myself unexpectedly moved by this book. In aggregate, all these stories of cannibalism—ravenous fish mothers eating their fry; doomed Donner Party pioneers roasting their dead—make for a kind of meditation on embodiment. After reading the book one evening, I fell asleep and dreamed of slicing up a steak. For days, I felt jumpy at the thought of being made of meat. The slabs of chicken flesh in the fridge, snug in their styrofoam-and-shrink-wrap nest, seemed as alien as cuts of dog.

I could not get over the strangeness of consumption: that we eat the muscles of chickens and fish; that my own flesh is built from the flesh of dead things; that, for all our fantasies of individualism, we live on a planet where bodies flow into other bodies. Americans consume, in total, around sixty billion pounds of animal flesh each year. A typical American carnivore will go through a literal ton of flesh each decade. Is cannibalism really that much stranger than all of this?

Conversations about violence and politics have a way of settling into abstractions. Maybe it’s too uncomfortable to realize that the consequences of ideas can be felt in the flesh. At the end of the book, Schutt wonders whether, in some nightmare climate change apocalypse, more people will be forced to resort to cannibalism. You don’t need nightmare scenarios, though, to take pause from the reminder that to be in a body is to enter a kind of pact: you must eat, and you can also be eaten. As the idiom goes, it’s a dog-eat-dog world.

Other imaginaries may see something liberating, even redeeming, in this. While reading Cannibalism, I kept thinking of David Shulman’s book The Hungry God, and particularly a 12th century South Indian story that Shulman examines at length.

One day, a Shiva-worshipper called Ciruttontar receives a visit from the god, who has disguised himself as a wandering ascetic. Eager to honor the holy man, Ciruttontar offers him a meal from any of his three herds. Shiva, in diguise, refuses. “The beast we eat is human,” he says—specifically healthy five year-old boys who have been willingly sacrificed by their parents.

This is a pointed request: Ciruttontar and his wife, Venkattammai, have only one child, a healthy five year-old son. They kill him, and their servant makes curries from the boy’s flesh. Ciruttontar serves this meal to the god, who invites him to sit down and eat—and then demands that Ciruttontar call his son to join them for supper. Powerless and confused, the devotee goes outside to call for the boy, at which point Shiva disappears, the child is reconstituted and restored to his parents, and the god reveals himself to them in his full divine form.

What can you even say? Shulman is interested in the parallels between the story and the binding of Isaac in the Book of Genesis. In particular, he is fascinated with the way both stories use violence to bring the divine down to earth. In this vein, he writes about a concept that he calls downward transcendence, borrowing a term from the great South Indian scholar-poet A.K. Ramanujan.

We may imagine prayers and sacrifices as being directed upward, using symbolism to translate physical actions into something more ethereal. But, Shulman suggests, stories about human sacrifice and cannibalism seem to do the opposite. They replace the symbolic with something carnal, literal, and base. And instead of lifting people up to the heavens, they tug the divine—or to use different language, they tug the abstract—down to earth.