Glenn Beck leans forward on his elbows. His voice hushes. His eyes grow red at the corners. He presses his lips together and clears his throat. He cannot speak. The tears fall, and just for a moment the brashest voice in American conservatism today falls silent.

This is what happens when Beck tells the story of his 1999 conversion to Mormonism.

“I was friendless, working in the smallest radio market I had ever worked in… a hopeless alcoholic, abusing drugs every day,” Beck said in an interview taped last fall. “I was trying to find a job and nobody would hire me… couldn’t get an agent to represent me.”

That’s when Beck’s wife-to-be Tania suggested that the family go on a “church tour,” which finally led (after some prodding from Beck’s longtime on-air partner Pat Gray, a Mormon) to his local Mormon wardhouse. Six months later, the Beck family joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

“I was baptized on a Sunday, and on Monday”—Beck’s throat tightens again; he wipes tears from his eyes with his index fingers—“an agent called me out of the blue.” Three days later, Beck was offered his own political talk radio show at WFLA-AM in Tampa, Florida, the job that put him on the road from “morning zoo” radio prankster to conservative media heavyweight.

Spiritual narratives of the I-once-was-lost-now-I-am-financially-sound variety are commonplace within Mormonism, which, like most of American Protestantism, has never been allergic to wealth. The institutional culture of the Mormon Church is strongly corporate, down to the dark suits, white shirts, and red or blue ties church leaders wear instead of vestments; Mormonism’s most powerful public figures like Mitt Romney, Jon Huntsman Jr., and Bill Marriott Jr., come from the business world.

But whether or not one believes that God rewards baptism with fortune, it is clear that Glenn Beck’s conversion to and education in the Mormon faith after 1999 corresponds precisely with his rise as a media force.

Beck, who was raised Catholic in Washington state, has produced, with the help of Mormon Church-owned Deseret Book Company, the DVD An Unlikely Mormon: The Conversion Story of Glenn Beck (2008); Mormon fansites invite visitors to learn more about Beck’s beliefs by clicking through to the official Web site of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. But what these fansites don’t reveal is the extent to which Mormonism has given Beck key elements of his on-air personality and messaging.

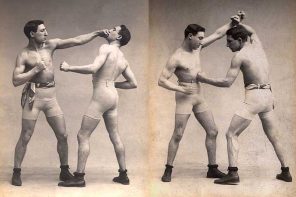

Teary Tirades and Mormon Masculinity

Before 1999, Glenn Beck told jokes and pulled on-air stunts for a living. He developed the content of his current conservative messaging (an amalgation of anti-communism, United States-founder worship, and connect-the-dots conspiracy theorizing) after his entree into the deeply insular world of Mormon thought and culture. A significant figure in this world is the late Cleon Skousen (1913–2006), the archconservative and fiercely anti-communist Brigham Young University professor, founder of the Freeman Society, and author of 15 books, including The Naked Capitalist, The Making of America, and Prophecy and Modern Times. Beck, who first cited Skousen in his 2003 book The Real America: Messages from the Heart and the Heartland, later started pitching Skousen’s 1981 book The 5,000 Year Leap on air in December, 2008. He wrote a preface for a new edition of the book issued a few months later and in his March 2009 kick-off of the 9/12 movement declared Skousen’s book to be “divinely inspired.” In a recent article for Salon.com, Alexander Zaitchik suggested that Beck “rescued [Skousen] from the remainder pile of history.” But Cleon Skousen was never remaindered among the most politically conservative Mormons, for whom he has been a household name since the 1960s.

It is likely that Beck owes his brand of Founding Father-worship to Mormonism, where reverence for the founders and the United States Constitution as divinely inspired are often-declared elements of orthodox belief. Mormon Church President Wilford Woodruff (1807–1898) declared that George Washington and the signers of the Declaration of Independence appeared to him in the Mormon Temple in St. George, Utah in 1877, and requested that he perform Mormon temple ordinances on their behalf. Many Mormons also believe that Joseph Smith prophesied in 1843 that the US Constitution would one day “hang by a thread” and be saved by faithful Mormons; this idea was given new life in the 1960s by former US Secretary of Agriculture Ezra Taft Benson, who cited Smith’s 1843 prophecy from the pulpit while speaking as a member of the Church’s Quorum of Twelve Apostles.

Many key elements of Beck’s on-the-fly messaging derive from a Mormon lexicon, such as his Twitter-issued September 19 call: “Sept 28. Lets make it a day of Fast and Prayer for the Republic. Spread the word. Let us walk in the founders steps.” This call to fasting and prayer may indeed have been an appropriation of the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur, but it is also rooted in the traditional Mormon practice of holding individual, familial, and collective fasts to address spiritual challenges.

Even the overt sentimentality Beck now indulges from time to time was formed within the cradle of Mormon literary culture. Take, for example, his novel The Christmas Sweater (2008) (co-authored by Mormon writer Jason Wright) and its accompanying children’s picture book, which tell the story of an impoverished twelve-year-old boy who rejects a “handmade, ugly sweater” his widowed mother knits him for Christmas, only to watch his mother die in a fiery car crash hours later. This punishing sentimentality is a consistent feature of Mormon storytelling from Church-produced cinematic classics like Cipher in the Snow (1973) and The Mailbox (1977) to the New York Times-bestselling novel The Christmas Box (1995) by Mormon author Richard Paul Evans.

Finally, Beck’s oft-ridiculed penchant for punctuating his tirades with tears is the hallmark of a distinctly Mormon mode of masculinity. As sociologist David Knowlton has written, “Mormonism praises the man who is able to shed tears as a manifestation of spirituality.” Crying and choking up are understood by Mormons as manifestations of the Holy Spirit. For men at every rank of Mormon culture and visibility, appropriately-timed displays of tender emotion are displays of power.

Peace on the Religious Right between Mormons and Evangelicals?

Indeed, Beck, who grew up without a father, narrates his conversion and personal transformation around a series of tearful bonding moments with Mormon men, from the Sunday School teacher who first taught him about the Mormon concept of Zion—“Tears started to roll down his cheeks, and he said, ‘It can only happen if I truly love you and you love me’”—to his baptism by immersion by his longtime friend Pat Gray, who was so choked up, according to Beck, that “he couldn’t get the words out.”

Not typical of Mormon masculinity are Beck’s high-decibel swings between bombast and self-deprecation. Such demonstrative excesses are socialized out of most Mormon men during a regimented process of masculine formation that begins with entry into the lowest ranks of Mormonism’s lay priesthood at age 12, intensifies during compulsory missionary service from age 19 through 21, and continues throughout a lifetime of service within hierarchical priesthood quorums. A textbook example of the traditional Mormon “man of steel and velvet” is Mitt Romney, whose inability to connect with the Republican base may have as much to do with his lack of familiar jocularity and chest-thumping outrage as it does with the perceived weirdness of his Mormon beliefs. As a convert, Beck missed out on crucial early years of Mormon male socialization. Consequently, his renegade persona may endear him even more to his Mormon male fans who might like to comport themselves as he does, but feel they cannot.

It’s true that his Mormonism sometimes gets Beck into trouble with evangelical Christians, who have long antagonized Mormons by denying the authenticity of their belief in Jesus Christ and deriding the Mormon Church as a cult. Last December, James Dobson’s Focus on the Family Web site pulled a Beck column, citing concerns about his Mormon ties. Still, Beck’s spectacular rise suggests that evangelical conservatives (especially those under 40 who may not remember the anti-Mormon cult crusades of the 1980s) are increasingly willing to set aside their reservations about Mormons when it suits their pragmatic and political interests.

Glenn Beck marks an unprecedented national mainstreaming of a peculiar strand of religious political conservatism rooted in, and once isolated to, the Mormon culture regions of the American West. That Mormons are capable of leveraging disproportionate political influence with decisive results was one of the great lessons of California’s 2008 election season, wherein readily-mobilized Mormons, who make up 2% of California’s population, contributed more than 50% of the individual donations to the successful anti-marriage equality Proposition 8 campaign, and a sizeable majority of its on-the-ground efforts.

How much traction Glenn Beck can muster remains to be seen. But if the American religious right has sometimes been imagined as a monolithic product of the evangelical Deep South and Bible Belt, the rise of Glenn Beck suggests that those who would understand American conservatism might also look West, toward Salt Lake City.